Date of Publishing:

From the Executive Director

I am pleased to present the 2025–26 Departmental Plan for the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat. This plan outlines the key priorities and objectives we will pursue in the coming year to support NSIRA’s critical work in ensuring accountability and public confidence in national security and intelligence activities.

The Secretariat’s role is to provide the expertise, resources, and support necessary for NSIRA to fulfill its mandate effectively. As we move forward, our focus remains on fostering a culture of professionalism, transparency, and continuous improvement. This commitment underpins all aspects of our work, from supporting independent reviews to facilitating timely and fair investigations.

The year ahead presents opportunities to strengthen our processes and refine how we deliver on our responsibilities. By building on the knowledge gained through past work, enhancing internal capabilities, and fostering collaboration with our partners, the Secretariat aims to ensure that NSIRA continues to deliver meaningful and high-quality results.

While challenges remain, including the complexity of accessing necessary information and managing procedural unpredictability, the Secretariat is committed to addressing these issues with diligence and care. Through clear communication, proactive engagement, and a steadfast focus on service standards, we will work to mitigate risks and achieve our planned results.

Our success is made possible by the dedication and professionalism of the Secretariat team. I am grateful for their continued efforts to support NSIRA’s mandate and to contribute to an accountable and transparent national security framework. I encourage you to review this Departmental Plan for more details on the priorities we have set and the results we aim to achieve in the year ahead.

Charles Fugère

Executive Director

National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat

Plans to deliver on core responsibilities and internal services

Core responsibilities and internal services:

- Core responsibility 1: National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations

- Internal services

Core responsibility 1: National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations

Description

NSIRA reviews Government of Canada national security and intelligence activities to assess whether they are lawful, reasonable, and necessary. NSIRA also investigates complaints from members of the public on the activities of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), as well as certain other national security-related complaints, independently and in a timely manner.

The NSIRA Secretariat supports the Agency in the delivery of its mandate. Independent scrutiny contributes to strengthening the accountability framework for national security and intelligence activities and to enhancing public confidence. Ministers and Canadians are informed whether national security and intelligence activities undertaken by Government of Canada institutions are lawful, reasonable, and necessary.

Quality of life impacts

The NSIRA Secretariat’s core responsibility relates most closely to the indicator ‘confidence in institutions‘, within the ‘democracy and institutions’ subdomain and under the overarching domain of ‘good governance’.

Indicators, results and targets

This section presents details on the department’s indicators, the actual results from the three most recently reported fiscal years, the targets and target dates approved in 2020-21 for National security and intelligence reviews and complaint investigations. Details are presented by departmental result.

Table 1: Ministers and Canadians are informed whether national security and intelligence activities undertaken by Government of Canada institutions are lawful, reasonable, and necessary.

Table 1 provides a summary of the target and actual results for each indicator associated with the results under National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations.

| Indicator | Actual Results | Target | Date to achieve |

|---|---|---|---|

| All mandatory reviews are completed on an annual basis |

2021–22: 100% 2022–23: 100% 2023–24: 100% |

100% completion of mandatory reviews | December 2022 |

| Reviews of national security or intelligence activities of at least five departments or agencies are conducted each year |

2021–22: 100% 2022–23: 100% 2023–24: 100% |

At least one national security or intelligence activity is reviewed in at least five departments or agencies annually | December 2022 |

| All Member-approved high priority national security or intelligence activities are reviewed over a three-year period |

2021–22: 33% 2022–23: 33% 2023–24: 33% |

100% completion over three years; at least 33% completed each year | December 2022 |

Table 2: National security-related complaints are independently investigated in a timely manner

| Indicator | Actual Results | Target | Date to achieve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of investigations completed within the NSIRA Secretariat service standards |

2021–22: N/A 2022–23: N/A 2023–24: 100% |

90% – 100% | March 2024 |

Additional information on the detailed results and performance information for the NSRIA Secretariat’s program inventory is available on GC InfoBase.

Plans to achieve results

The following section describes the planned results for National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations in 2025-26.

Ministers and Canadians are informed whether national security and intelligence activities undertaken by Government of Canada institutions are lawful, reasonable and necessary.

Results we plan to achieve

- Review work will be informed and guided by the knowledge and experience acquired through previous reviews, and this increased understanding of departments and agencies’ organizational structures, networks, policies, and activities will be leveraged and applied to both the selection and execution of our reviews.

- All current and ongoing reviews, and new reviews beginning in 2025-26, will be conducted with the highest degree of rigour and professionalism. This will include all mandatory and discretionary reviews, including annual reviews of CSIS and CSE activities.

- Review reports, which capture the detailed results and outcomes of our reviews, will be produced and provided to applicable Ministers and departments, including all findings, and recommendations produced during the review.

- All review reports will be prepared for public release as a result of Access to Information requests and also published on the NSIRA website, allowing Canadians to see the outcomes and conclusions of NSIRA’s work, which assesses whether the national security and intelligence activities undertaken by Government of Canada institutions are lawful, reasonable and necessary.

- To further support its review efforts, the Secretariat will continue to leverage and foster its bilateral and multilateral international and domestic partnerships in the review and oversight community. Such participation and engagement expand the knowledge and experience base of the Secretariat through the sharing of best practices. It also allows the Secretariat to grow NSIRA’s visibility globally and sets up Canada amongst the industry leaders in review and oversight.

National security-related complaints are independently investigated in a timely manner

Results we plan to achieve

- The Secretariat will revise and amend NSIRA’s Rules of Procedure and Standard Operating Procedures for complaint investigations. These revisions will allow for consistency with developed best practices and ensure the continued modernization of its processes.

- The Secretariat will develop a simplified procedure to support NSIRA in addressing large volumes of particular types of complaint allegations, or individual complaints requiring a narrower evidentiary scope to in turn promote timeliness, efficiency, and procedural fairness.

- The Secretariat will continue the development and integration of a multi-disciplined work environment composed of necessary expertise to enhance the professionalization of NSIRA’s investigations and investigative processes.

- The Secretariat will leverage its strong relationships with partners to commence work on developing procedures for all phases of the investigation of complaints against the RCMP and CBSA related to national security in preparation for the eventual coming into force of the PCRC Act, and this will include the completion of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Civilian Review and Complainants Commission (CRCC) / the PCRC.

- The Secretariat will also leverage those relationships as it prepares to support the new PCRC with its statutory obligation under the PCRC Act to report race-based and other demographic data related to complaints against the RCMP and the CBSA, namely by ensuring that NSIRA consistently reports, as necessary, on such data for complaints referred to it by the PCRC.

Key risks

The NSIRA Secretariat has made progress on accessing the information required to conduct reviews; however, there continues to be risk associated with reviewees’ ability to respond to and prioritize information requests, or to provide necessary access to required information during reviews, thereby hindering NSIRA’s ability to deliver its reviews on a faster turnaround. The NSIRA Secretariat will continue to mitigate these risks by providing clear communication related to information requests, tracking their timely completion within communicated timelines and escalating issues when appropriate.

With respect to the Secretariat’s service standards, one risk to the achievement of the planned results for complaint investigations is the procedural unpredictability of NSIRA’s investigations due to the quasi-judicial nature of the investigation process and the institutional independence of individual NSIRA members in the conduct of their investigations.

Additionally, procedural unpredictability may result in some investigations becoming more protracted than others depending on the complexity of the complaint that NSIRA must address.

Finally, there is a risk to the timeliness of complaint investigations due to the responses from the respondent agencies and organizations whose activities are the subject of complaints. The timely provision of documents and the availability of individuals for interviews, by both the complainant and respondent agency, is necessary for NSIRA to conduct investigations in a timely manner and for the Secretariat to meet its service standards. Similar to NSIRA’s reviews, there continues to be a risk that government party respondents will not provide NSIRA with the documentary evidence it requires within the deadlines set by NSIRA. The is illustrated in ongoing litigation efforts against NSIRA’s access rights. The Secretariat will continue to support NSIRA in communicating expectations and deadlines clearly and consistently to parties and to coordinate NSIRA representation before the federal court in associated litigation matters.

Planned resources to achieve results

Table 3: Planned resources to achieve results for National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations

Table 3 provides a summary of the planned spending and full-time equivalents required to achieve results.

| Resource | Planned |

|---|---|

| Spending | $11,280,435 |

| Full-time equivalents | 69 |

Complete financial and human resources information for the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat’s program inventory is available on GC InfoBase.

Related government priorities

United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the UN Sustainable Development Goals

The NSIRA Secretariat’s contributes to implementing the 2030 Agenda and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Through its Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy for 2023-2027, the NSIRA Secretariat supports SDGs 10 (Reduced Inequalities), 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and 13 (Climate Action) by ensuring that its operations and activities align with principles of sustainability, social equity, and environmental responsibility. The Secretariat’s initiatives aim to foster a balanced approach to sustainable development while contributing to Canada’s progress in achieving the global SDG targets.

More information on the NSIRA Secretariat’s contributions to Canada’s Federal Implementation Plan on the 2030 Agenda and the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy can be found in our Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy.

Program inventory

National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations are supported by the following program in the program inventory:

- National security and intelligence activity reviews and complaints investigations.

Supporting information on planned expenditures, human resources, and results related to the NSIRA Secretariat’s program inventory is available on GC Infobase.

Internal services

Description

Internal services are the services that are provided within a department so that it can meet its corporate obligations and deliver its programs. There are 9 categories of internal services:

- management and oversight services

- communications services

- human resources management services

- financial management services

- information management services

- information technology services

- real property management services

- materiel management services

- acquisition management services

Plans to achieve results

This section presents details on how the department plans to achieve results and meet targets for internal services.

Efficient Resource Deployment and Operational Support

In 2025–26, the NSIRA Secretariat will continue to take steps to ensure resources are deployed in the most effective and efficient manner possible, and its operations and administrative structures, tools, and processes continue to focus on supporting the delivery of its priorities. The NSIRA Secretariat will work to formalize and document some key policies, directives and guidelines for the finance and procurement operations.

Strategic Human Resources Focus

HR services play a pivotal role in achieving organizational goals by fostering a high performing, engaged, and adaptable workforce. The HR strategic focus emphasizes enhancing processes through innovative talent acquisition, employee development, and retention strategies aligned with the organization’s mission and values. Revamped developmental programs, tailored training opportunities, mentorship initiatives, and clear pathways for professional growth ensure employees are well-equipped to meet evolving needs. Furthermore, the NSIRA Secretariat has made notable progress in employee retention, driven by a commitment to a positive workplace culture These efforts, along with wellness initiatives, and a collaborative culture, enhance job satisfaction and long-term retention, enabling the organization to thrive.

Enhancing Collaboration and Accessibility

There are plans to revamp our internal systems to improve collaboration and enhance information accessibility across teams. Additionally, we will optimize the NSIRA’s external website to ensure better accessibility and alignment with organizational objectives. These efforts are designed to streamline information-sharing practices, increase operational efficiency, and foster a more connected and collaborative work environment. Through these plans, the NSIRA Secretariat will enhance both internal and external communications, ensuring that technology supports the department’s broader goals.

Modernizing Information Management and Archival Practices

The NSIRA Secretariat plans to establish comprehensive archival management and compliance standards for the physical archive to meet both regulatory and organizational requirements. A key focus will be the modernization of information management policy instruments, ensuring that data handling and storage practices align with contemporary best practices in the field. During 2025-2026, the NSIRA Secretariat will implement its new Disposition Authority, which will guide the retention and disposal of records in accordance with established guidelines. Additionally, a targeted approach will be taken to strengthen the use of GCdocs, enhancing its capabilities for effective information management across the NSIRA Secretariat. These efforts will ensure robust operations and provide the necessary structure to support efficient information governance.

Strengthening Risk Management Frameworks

To strengthen the department’s risk management capabilities, the plan includes the ongoing implementation and updating of security controls and risk-based procedures to ensure their continued relevance and resilience in the face of emerging threats. This will be supported by the strengthening of the internal risk program framework, including the development of more effective tools to assess, manage, and mitigate risks across the organization. By enhancing these risk management strategies, the NSIRA Secretariat will be better equipped to safeguard its operations and assets, while fostering a culture of proactive risk management that supports the achievement of organizational objectives.

Planned resources to achieve results

Table 4: Planned resources to achieve results for internal services this year

Table 4 provides a summary of the planned spending and full-time equivalents required to achieve results.

| Resource | Planned |

|---|---|

| Spending | $8,164,617 |

| Full-time equivalents | 31 |

Complete financial and human resources information for the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat’s program inventory is available on GC InfoBase.

Planning for contracts awarded to Indigenous businesses

Government of Canada departments are to meet a target of awarding at least 5% of the total value of contracts to Indigenous businesses each year. This commitment is to be fully implemented by the end of 2024-25.

As part of the government-wide phased approach, the NSIRA Secretariat is progressing toward this goal. Efforts are already well underway in support of the Government of Canada’s commitment, which requires that at least 5% of the total value of contracts be awarded to Indigenous businesses annually.

In 2023–24, the NSIRA Secretariat was well on its way to achieving the 5% goal by 2024–25, having reached 3%, as shown in Table 5. Measures to meet the mandatory target include increasing the number of contracts set aside for Indigenous businesses under the Procurement Strategy for Indigenous Business over the next three fiscal years.

Table 5: Percentage of contracts planned and awarded to Indigenous businesses

Table 5 presents the current, actual results with forecasted and planned results for the total percentage of contracts the department awarded to Indigenous businesses.

| 5% Reporting Field | 2023–24 Actual Result | 2024–25 Forecasted Result | 2025–26 Planned Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total percentage of contracts with Indigenous businesses | 3% | 5% | 5% |

Planned spending and human resources

This section provides an overview of National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat’s planned spending and human resources for the next three fiscal years and compares planned spending for 2025-26 with actual spending from previous years.

Spending

This section presents an overview of the department’s planned expenditures from 2022-23 to 2027-28.

Graph 1 Planned spending by core responsibility in 2025-26

Graph 1 presents how much the department plans to spend in 2025-26 to carry out core responsibilities and internal services.

Graph 1 is a bar graph that demonstrates how much the department plans to spend on core responsibilities and internal services by year from 2022-23 through 2027-28.

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2025–26 Planned Spending |

|---|---|

| National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations | $11,280,435 |

| Internal services | $8,164,617 |

Analysis of planned spending by core responsibility

Yearly spending to carry out core responsibilities and internal services has remained steady in total as well as with respect to the ratio of statutory to voted expenditures. This is expected to remain relatively stable as the organization reaches its steady state.

Budgetary performance summary

Table 6 Three-year spending summary for core responsibilities and internal services (dollars)

Table 6 presents how much money the NSIRA Secretariat spent over the past three years to carry out its core responsibilities and for internal services. Amounts for the current fiscal year are forecasted based on spending to date.

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2022–23 Actual Expenditures | 2023–24 Actual Expenditures | 2024–25 Forecast Spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations | $7,756,271 | $9,110,398 | $11,303,742 |

| Subtotal | $7,756,271 | $9,110,398 | $11,303,742 |

| Internal services | $10,532,876 | $10,535,328 | $8,181,486 |

| Total | $18,289,147 | $19,645,726 | $19,485,229 |

Analysis of the past three years of spending

While planned spending appears to have remained constant over the last 3 years and is expected to stay the same, the composition of expenditures has changed from fiscal year 2022-23 to 2024-25. A large capital infrastructure project was underway in 2022-23 and was completed in 2023-24, inflating expenditures in internal services. Since 2022-23, we have seen a gradual increase in both ongoing O&M expenditures and salaries, due to the growth of the organization and the approach towards a steady state.

More financial information from previous years is available on the Finances section of GC Infobase.

Table 7 Planned three-year spending on core responsibilities and internal services (dollars)

Table 7 presents how much money the NSIRA Secretariat plans to spend over the next three years to carry out its core responsibilities and for internal services.

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2025–26 Planned Spending | 2026–27 Planned Spending | 2027–28 Planned Spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations | $11,280,435 | $11,296,175 | $11,296,175 |

| Subtotal | $11,280,435 | $11,296,175 | $11,296,175 |

| Internal services | $8,164,617 | $8,176,009 | $8,176,009 |

| Total | $19,445,052 | $19,472,184 | $19,472,184 |

Analysis of the next three years of spending

With the maturing of the organization, overall planned spending is expected to remain constant for the foreseeable future. The organization’s funding has been regularized, so there are no significant variances to report.

More detailed financial information on planned spending is available on the Finances section of GC Infobase.

Information on the alignment of the NSIRA Secretariat’s spending with Government of Canada’s spending and activities is available on GC InfoBase.

Funding

This section provides an overview of the department’s voted and statutory funding for its core responsibilities and for internal services. For further information on funding authorities, consult the Government of Canada budgets and expenditures.

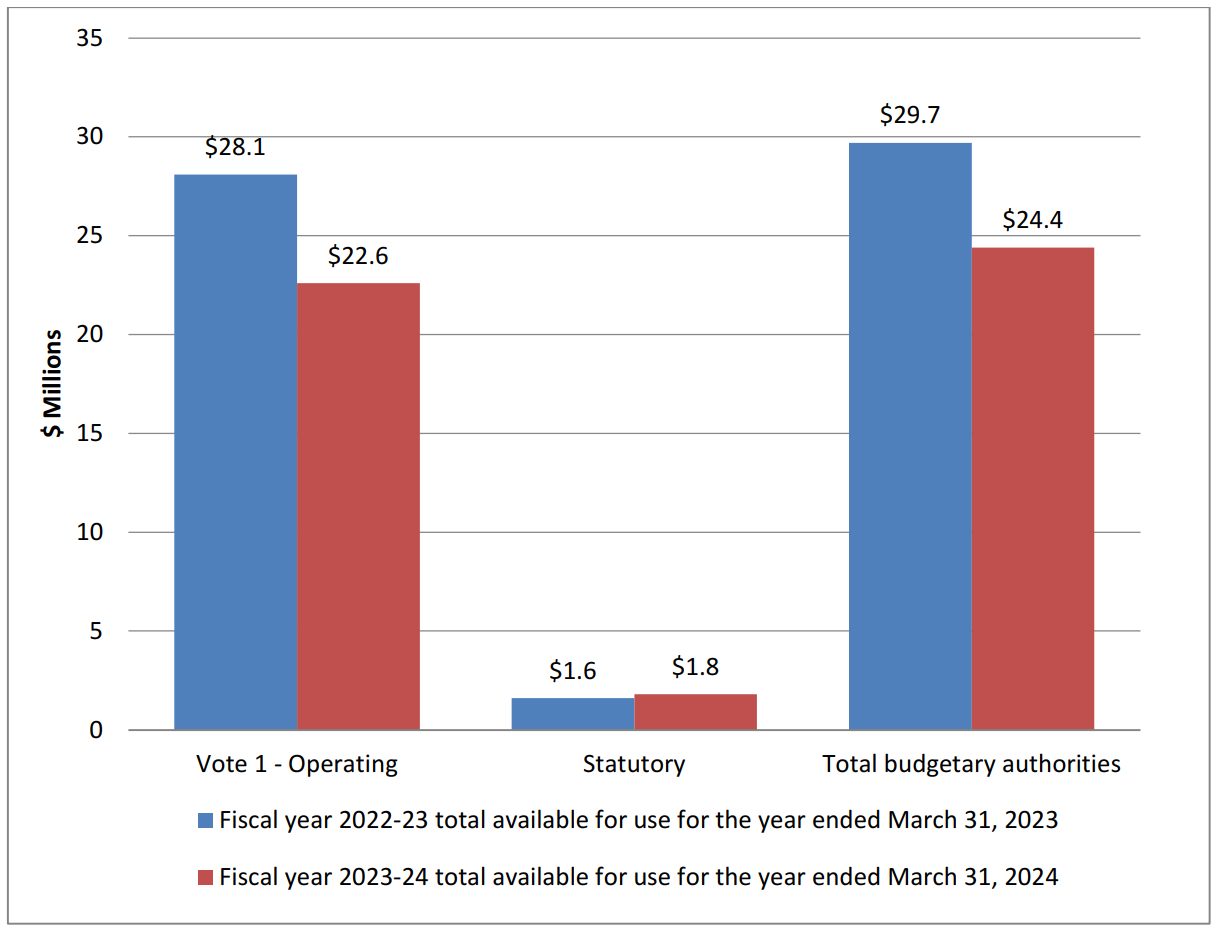

Graph 2: Approved funding (statutory and voted) over a six-year period

Graph 2 summarizes the department’s approved voted and statutory funding from 2022-23 to 2027-28.

Graph 2 is a bar graph that summarizes the department’s approved voted and statutory funding from 2022-23 to 2027-28

| Fiscal Year | Total | Voted | Statutory |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022–23 | $29,791,019 | $28,063,351 | $1,727,668 |

| 2023–24 | $24,388,394 | $22,633,165 | $1,755,229 |

| 2024–25 | $19,458,632 | $17,857,264 | $1,601,368 |

| 2025–26 | $19,445,052 | $17,697,005 | $1,748,047 |

| 2026–27 | $19,472,184 | $17,720,195 | $1,751,989 |

| 2027–28 | $19,472,184 | $17,720,195 | $1,751,989 |

Analysis of statutory and voted funding over a six-year period

With NSIRA being created in 2019, additional space was required to accommodate the intended steady state of FTEs within the organization. To address this need, a large capital infrastructure project was funded until March 2024, even though the project was completed in August 2024. This timing explains the decrease in funding in 2023–24 and again in 2024–25. From 2024–25 onward, the organization has nearly reached its anticipated steady state, which is reflected in a consistent yearly budget.

For further information on the NSIRA Secretariat’s departmental appropriations, consult the 2025-26 Main Estimates.

Future-oriented condensed statement of operations

The future-oriented condensed statement of operations provides an overview of the NSIRA Secretariat’s operations for 2024-25 to 2025-26.

Table 8 Future-oriented condensed statement of operations for the year ended March 31, 2026 (dollars)

Table 8 summarizes the expenses and revenues which net to the cost of operations before government funding and transfers for 2024-25 to 2025-26. The forecast and planned amounts in this statement of operations were prepared on an accrual basis. The forecast and planned amounts presented in other sections of the Departmental Plan were prepared on an expenditure basis. Amounts may therefore differ.

| Financial Information | 2024–25 Forecast Results | 2025–26 Planned Results | Difference (Planned Results minus Forecasted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | $21,201,414 | $21,394,362 | $192,948 |

| Total revenues | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers | $21,201,414 | $21,394,362 | $192,948 |

Analysis of forecasted and planned results

While there are no significant variances between planned 2025-26 and forecasted 2024-25 results, small increases in both the amortization of tangible capital assets and services provided without charge are anticipated due to the completion of a large infrastructure project which was converted from an asset under construction to an asset mid-year 2024-25.

A more detailed Future-Oriented Statement of Operations and associated Notes for 2025-26, including a reconciliation of the net cost of operations with the requested authorities, is available on the NSIRA Secretariat’s website.

Human resources

This section presents an overview of the department’s actual and planned human resources from 2022-23 to 2027-28.

Table 9: Actual human resources for core responsibilities and internal services

Table 9 shows a summary of human resources, in full-time equivalents, for the NSIRA Secretariat’s core responsibilities and for its internal services for the previous three fiscal years. Human resources for the current fiscal year are forecasted based on year to date.

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2022–23 Actual Full-time Equivalents | 2023–24 Actual Full-time Equivalents | 2024–25 Forecasted Full-time Equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|

| National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations | 53 | 51 | 69 |

| Subtotal | 53 | 51 | 69 |

| Internal services | 25 | 24 | 31 |

| Total | 78 | 75 | 100 |

Analysis of human resources over the last three years

Our full-time employee count has shown significant progress over the past year, reflecting our continued growth and commitment to expanding our organisation. The turnover rate was significantly lower this year, largely attributed to the organization’s strong commitment to fostering a healthy workplace culture for its employees. The NSIRA Secretariat has empowered its staff and managers to organize their professional responsibilities effectively. This is complemented by efforts to implement clear organizational priorities and break down organizational silos. Additionally, the organization provides resources that promote mental and physical health, creating a supportive environment where employees feel valued. These initiatives are combined with professional growth opportunities and a collaborative culture..

Table 10: Human resources planning summary for core responsibilities and internal services

Table 10 shows information on human resources, in full-time equivalents, for each of the NSIRA Secretariat’s core responsibilities and for its internal services planned for the next three years.

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2025–26 Planned Full-time Equivalents | 2026–27 Planned Full-time Equivalents | 2027–28 Planned Full-time Equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|

| National security and intelligence reviews and complaints investigations | 69 | 69 | 69 |

| Subtotal | 69 | 69 | 69 |

| Internal services | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Total | 31 | 31 | 31 |

Analysis of human resources for the next three years

The NSIRA Secretariat expects to be fully staffed as of 2025-26. Attrition is predicted to be low in the coming years, therefore, the NSIRA Secretariat projects a steady level of staffing year to year.

Corporate information

Departmental profile

Appropriate minister(s): The Right Honourable Mark Carney, Prime Minister of Canada

Institutional head: Charles Fugère, Executive Director

Ministerial portfolio: Privy Council Office

Enabling instrument(s): National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act

Year of incorporation / commencement: 2019

Departmental contact information

Mailing address:

National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat P.O. Box 2430, Station B

Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5W5

Email: info@nsira-ossnr.gc.ca

Website(s): nsira-ossnr.gc.ca

Federal tax expenditures

The NSIRA Secretariat’s Departmental Plan does not include information on tax expenditures.

The tax system can be used to achieve public policy objectives through the application of special measures such as low tax rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits. The Department of Finance Canada publishes cost estimates and projections for these measures each year in the Report on Federal Tax Expenditures.

This report also provides detailed background information on tax expenditures, including descriptions, objectives, historical information and references to related federal spending programs as well as evaluations and GBA Plus of tax expenditures.

Appendix: definitions

appropriation (crédit)

Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

budgetary expenditures (dépenses budgétaires)

Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

core responsibility (responsabilité essentielle)

An enduring function or role performed by a department. The intentions of the department with respect to a core responsibility are reflected in one or more related departmental results that the department seeks to contribute to or influence.

Departmental Plan (plan ministériel)

A report on the plans and expected performance of an appropriated department over a 3year period. Departmental Plans are usually tabled in Parliament each spring.

departmental result (résultat ministériel)

A consequence or outcome that a department seeks to achieve. A departmental result is often outside departments’ immediate control, but it should be influenced by program-level outcomes.

departmental result indicator (indicateur de résultat ministériel)

A quantitative measure of progress on a departmental result.

departmental results framework (cadre ministériel des résultats)

A framework that connects the department’s core responsibilities to its departmental results and departmental result indicators.

Departmental Results Report (rapport sur les résultats ministériels)

A report on a department’s actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

full‑time equivalent (équivalent temps plein)

A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person‑year charge against a departmental budget. For a particular position, the full‑time equivalent figure is the ratio of number of hours the person actually works divided by the standard number of hours set out in the person’s collective agreement.

gender-based analysis plus (GBA Plus) (analyse comparative entre les sexes plus [ACS Plus])

Is an analytical tool used to support the development of responsive and inclusive policies, programs, and other initiatives. GBA Plus is a process for understanding who is impacted by the issue or opportunity being addressed by the initiative; identifying how the initiative could be tailored to meet diverse needs of the people most impacted; and anticipating and mitigating any barriers to accessing or benefitting from the initiative. GBA Plus is an intersectional analysis that goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences to consider other factors, such as age, disability, education, ethnicity, economic status, geography (including rurality), language, race, religion, and sexual orientation.

Using GBA Plus involves taking a gender- and diversity-sensitive approach to our work. Considering all intersecting identity factors as part of GBA Plus, not only sex and gender, is a Government of Canada commitment.

government priorities (priorités gouvernementales)

For the purpose of the 2025-26 Departmental Plan, government priorities are the high-level themes outlining the government’s agenda in the most recent Speech from the Throne.

horizontal initiative (initiative horizontale)

An initiative where two or more federal departments are given funding to pursue a shared outcome, often linked to a government priority.

Indigenous business (entreprise autochtones)

For the purpose of the Directive on the Management of Procurement Appendix E: Mandatory Procedures for Contracts Awarded to Indigenous Businesses and the Government of Canada’s commitment that a mandatory minimum target of 5% of the total value of contracts is awarded to Indigenous businesses, a department that meets the definition and requirements as defined by the Indigenous Business Directory.

non‑budgetary expenditures (dépenses non budgétaires)

Non-budgetary authorities that comprise assets and liabilities transactions for loans, investments and advances, or specified purpose accounts, that have been established under specific statutes or under non-statutory authorities in the Estimates and elsewhere. Non-budgetary transactions are those expenditures and receipts related to the government’s financial claims on, and obligations to, outside parties. These consist of transactions in loans, investments and advances; in cash and accounts receivable; in public money received or collected for specified purposes; and in all other assets and liabilities. Other assets and liabilities, not specifically defined in G to P authority codes are to be recorded to an R authority code, which is the residual authority code for all other assets and liabilities.

performance (rendement)

What a department did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compare to what the department intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

performance indicator (indicateur de rendement)

A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

plan (plan)

The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how a department intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally, a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead to the expected result.

planned spending (dépenses prévues)

For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts presented in Main Estimates.

A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports.

program (programme)

Individual or groups of services, activities or combinations thereof that are managed together within the department and focus on a specific set of outputs, outcomes or service levels.

program inventory (répertoire des programmes)

Identifies all the department’s programs and describes how resources are organized to contribute to the department’s core responsibilities and results.

result (résultat)

A consequence attributed, in part, to a department, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single department, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the department’s influence.

statutory expenditures (dépenses législatives)

Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

target (cible)

A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

voted expenditures (dépenses votées)

Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an appropriation act. The vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.