Date of Publishing:

Executive Summary

The CSE Act provided CSE with the authority to conduct Active and Defensive Cyber Operations (ACO/DCO). As defined by the Act, a DCO stops or impedes foreign cyber threats from Canadian federal government networks or systems deemed by the Minister of National Defence (MND) as important to Canada. On the other hand, ACOs intend to limit an adversary’s ability to affect Canada’s international relations, defence, or security. ACO/DCOs are authorized by Ministerial Authorizations (MA) and, due to the potential impact on Canadian foreign policy, require the Minister of Foreign Affairs (MFA) to either consent or be consulted on ACO and DCO MAs respectively.

In this review, NSIRA set out to assess the governance framework that guides the conduct of ACO-DCOs, and to assess if CSE appropriately considered its legal obligations and the foreign policy impacts of operations. NSIRA analyzed policies and procedures, governance and operational documentation, and correspondence within and between CSE and GAC. The review began with the earliest available materials pertaining to ACO/DCOs and ended concurrently with the validity period of the first ACO/DCO Ministerial Authorizations.

NSIRA incorporated GAC into this review given its key role in the ACO/DCO governance structure arising from the legislated requirement for the role of the MFA in relation to the MAs. As a result, NSIRA was able to gain an understanding of the governance and accountability structures in place for these activities by obtaining unique perspectives from the two departments on their respective roles and responsibilities.

The novelty of these powers required CSE to develop new mechanisms and processes while also considering new legal authorities and boundaries. NSIRA found that considerable work has been conducted in building the ACO/DCO governance structure by both CSE and GAC. In this context, NSIRA has found that some aspects of the governance of can be improved by making them more transparent and clear.

Specifically, NSIRA found that CSE can improve the level of detail provided to all parties involved in the decision-making and governance of ACO/DCOs, within documents such as the MAs authorizing these activities and the operational plans that are in place to govern their execution. Additionally, NSIRA found that CSE and GAC have not sufficiently considered several gaps identified in this review, and recommended improvements relating to:

- The need to engage other departments to ensure an operation’s alignment with broader Government of Canada priorities,

- The lack of a threshold demarcating an ACO and a pre-emptive DCO,

- The need to assess each operation’s compliance with international law, and

- The need for bilateral communication of newly acquired information that is relevant to the risk level of an operation.

The gaps observed by NSIRA are those that, if left unaddressed, could carry risks. For instance, the broad and generalized nature of the classes of activities, techniques, and targets [**redacted**] ACO/DCOs can capture unintended [**redacted**] activities and targets. Additionally, given the difference in the required engagement of GAC in ACOs and DCOs, misclassifying what is truly an ACO as a pre-emptive DCO could result in a heightened risk to Canada’s international relations through the insufficient engagement of GAC.

While this review focused on the governance structures at play in relation to ACO/DCOs, of even greater importance is how these structures are implemented, and followed, in practice. We have made several observations about the information contained within the governance documents developed to date, and will subsequently assess how they are put into practice as part of our forthcoming review of ACO/DCOs.

The information provided by CSE has not been independently verified by NSIRA. Work is underway to establish effective policies and best practices for the independent verification of various kinds of information, in keeping with NSIRA’s commitment to a ‘trust but verify’ approach.

Authorities

This review was conducted pursuant to paragraphs 8(1)(a) and 8(1)(b) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) Act.

Introduction

Review background and methodology

With the coming into force of the CSE Act on August 1, 2019, CSE received the authority to independently conduct Active and Defensive Cyber Operations (“Active and Defensive Cyber Operations,” or ACO/DCOs henceforth) for the first time. While initial briefings on the subject in late fall of 2019 conveyed to NSIRA [**relates to CSE operations**] CSE later explained that [**redacted**].In this context, NSIRA will be assessing ACO/DCOs in a staged approach. The objective of this review is to better understand CSE’s development of a governance structure for ACO/DCOs. NSIRA will follow up with a subsequent review of the operations. This subsequent review is underway, with completion expected in 2022.

This review pertained to the structures put in place by CSE to govern the conduct of ACO/DCOs. Governance in this context can pertain to the establishment of processes to guide and manage planning, inter-departmental engagement, compliance, training, monitoring, and other overarching issues that affect the conduct of ACO/DCOs. NSIRA recognizes that these structures may be revised over time based on lessons learned from operations. Canada’s allies, who have had similar powers to conduct cyber operations for many years, [**relates to foreign partners’ capabilities**]. In this context, as its objectives, NSIRA sought out to determine if, in developing a governance structure for ACO/DCOs at this early stage, CSE appropriately considered and defined its legal obligations, and the foreign policy and operational components of ACO/DCOs.

As part of this governance review, NSIRA assessed policies, procedures, governance and operational planning documents, risk assessments, and correspondence between CSE and GAC (whose key role in this process is described below). NSIRA reviewed the earliest available materials relating to the development of the ACO/DCO governance structure, with the review period ending concurrent with the validity period of the first ACO/DCO Ministerial Authorizations on August 24, 2020. As such, the findings and recommendations made throughout this report pertain to the governance structure as it was presented during the period of review.

What are Active and Defensive Cyber Operations?

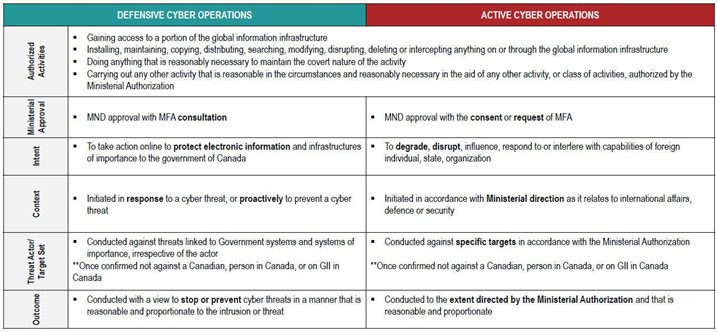

As defined in the CSE Act, Defensive Cyber Operations (DCOs) are those that stop or impede foreign cyber threats before they reach Canadian federal government systems or networks and systems designated by the Minister of National Defence (MND) as being of importance to Canada, such as Canada’s critical infrastructures and registered political parties. Active Cyber Operations (ACOs), on the other hand, allow the government to use CSE’s online capabilities to undertake a range of activities in cyberspace that limit an adversary’s ability to negatively impact Canada’s international relations, defence, or security, without their knowledge or consent. ACOs can include, for example, activities that disable communications devices used by a foreign terrorist network to communicate or plan attacks. The impacts of ACO/DCOs, [**relates to CSE operations**] of an ACO/DCO.

To conduct ACO/DCOs, CSE relies on its existing access to the global information infrastructure (GII), foreign intelligence expertise, and domestic and international partnerships to obtain relevant intelligence to support the informed development of ACO/DCOs. Activities conducted under CSE’s foreign intelligence and cybersecurity mandates allow CSE to gather information related to the intent, plans, and activities of actors seeking to disrupt or harm Canadian interests. According to CSE, the preliminary gathering of intelligence, capability development, [**redacted**] comprises the majority of the work necessary to conduct an ACO/DCO whereas the resulting activity in cyberspace is considered to be [**redacted**] of the task.

Legal foundation for conducting cyber operations

The CSE Act provides the legal authority for CSE to conduct ACO/DCOs, and these aspects of the mandate are described in the Act as per Figure 1. The ministerial authorization regime in the CSE Act provides CSE with the authority to conduct the activities or classes of activities listed in section 31 of the CSE Act in furtherance of the ACO/DCO aspects.

Defensive Cyber Operations (DCOs)

- Section 18 of the CSE Act

- The defensive cyber operations aspect of the Establishment’s mandate is to carry out activities on or through the global information infrastructure to help protect

- (a) federal institutions’ electronic information and information infrastructures; and

- (b) electronic information and information infrastructures designated … as being of importance to the Government of Canada.

Active Cyber Operations (ACOs)

- Section 19 of the CSE Act

- The active cyber operations aspect of the Establishment’s mandate is to carry out activities on or through the global information infrastructure to degrade, disrupt, influence, respond to, or interfere with the capabilities, intentions, or activities of a foreign individual, state, organization, or terrorist group as they relate to international affairs defence or security.

Importantly, the Act limits ACO/DCOs in that they cannot be directed at Canadians or any person in Canada and cannot infringe on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms; nor can they be directed at any portion of the GII within Canada.

ACO/DCOs must be conducted under a Ministerial Authorization (MA) issued by the MND under subsection 29(1) (DCO) or under subsection 30(1) (ACO) of the CSE Act. ACO/DCO MAs permit CSE to conduct ACO/DCO activities despite any other Act of Parliament or of any foreign state. In order to issue an MA, the MND must conclude that there are reasonable grounds to believe that any activity is reasonable and proportionate, and must also conclude that the objective of the cyber operation could not reasonably be achieved by other means. In addition, the MND must consult with the Minister of Foreign Affairs (MFA) in order to issue DCO MAs, and must obtain the MFA’s consent in order to issue ACO MAs. Any authorized ACO/DCO activities cannot cause, intentionally or by criminal negligence, death or bodily harm to an individual; or willfully attempt in any manner to obstruct, pervert, or defeat the course of justice or democracy. Importantly, unlike the MAs issued under the foreign intelligence, and cybersecurity and information assurance aspects of CSE’s mandate, ACO and DCO MAs are not subject to approval by the Intelligence Commissioner.

In addition to the ACO/DCO aspects of its mandate, CSE may also conduct ACO/DCO activities through technical and operational assistance to other Government of Canada (GC) departments. CSE may assist federal law enforcement and security agencies (LESAs) for purposes such as preventing criminal activity, reducing threats to the security of Canada, and supporting GC- authorized military missions. When providing assistance, CSE operates entirely within the legal authorities and associated limitations of the department requesting the assistance. Similarly, persons acting on CSE’s behalf also benefit from the same exemptions, protections and immunities as persons acting on behalf of the requesting LESAs. These assistance activities will be reviewed in subsequent NSIRA reviews.

In addition to the CSE Act, international law forms part of the legal framework in which ACO/DCO activities are conducted. Customary international law is binding on CSE’s activities, as Canadian law automatically adopts customary international law through the common law, unless there is conflicting legislation.

NSIRA notes that international law in cyberspace is a developing area. There is limited general state practice, or opinio juris (i.e, state belief that such practice amounts to a legal obligation), or treaty law, which elaborates on how international law applies in the cyber context. Moreover, while Canada has publically articulated that international law applies in cyberspace, it has not articulated a position on how it believes international law applies in cyberspace. At the same time, Canada has committed to building a common understanding between states of agreed voluntary non-binding norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace. NSIRA will closely monitor this emerging area of international law, including State practice in relation to CSE’s ACO/DCO activities – particularly in assessing CSE and GAC’s consideration of applicable international law as part of our subsequent review of ACO/DCOs.

Policy framework guiding cyber operations

Development of GAC-CSE framework for consultation

Conducting ACO/DCOs may elevate risks to Canada’s foreign policy and international relations. While CSE’s foreign intelligence mandate seeks only to collect information, ACO/DCOs [**redacted**]. As GAC is the department responsible for Canada’s international affairs and foreign policy, the MFA has a legislated role to play in consenting to MND’s issuance of an ACO Ministerial Authorization.

As directed by the MFA, CSE and GAC worked together to develop a framework for collaboration on matters related to ACO/DCOs. CSE and GAC began to engage on these matters before the coming into force of the CSE Act to proactively address the consultation and consent requirements embedded in the Act. Together, CSE and GAC have developed various interdepartmental bodies related to ACO/DCOs to facilitate consultation at different levels, including working groups at the levels of Director General and Assistant Deputy Minister.

CSE Governance Structure

CSE’s Mission Policy Suite (MPS) details the authorities in place to guide ACO/DCOs, prohibited activities when conducting ACO/DCOs and guidance in interpreting these prohibitions, as well as the governance framework to oversee the development and conduct of ACO/DCOs – known as the Joint Planning and Authorities Framework (JPAF). The general structure of this governance framework and process is intended to be used for all ACO/DCOs, irrespective of their risk-level. However, depending on the risk level of the operations, the framework sets out the specific approval levels.

During the period of review, the JPAF comprised several components required to plan, approve, and conduct cyber operations. The primary planning instrument for ACO/DCOs was [**relates to CSE operations**] that detailed the [**redacted**] identified [**redacted**] and highlighted risks and mitigations. [**redacted**] is used to determine and enumerate a range of risks associated with any new activity. In this period, CSE developed [**redacted**] NSIRA also received these documents [**redacted**] that fell slightly outside the review period, but provided relevant insight into the governance structure at the operation level.

Two primary internal working groups exist to evaluate and approve CSE’s internal plans for ACO/DCOs. The Cyber Operations Group (COG) is a Director-level approval body composed of key stakeholders and is chaired by the Director of the operational area that has initiated or sponsored a cyber operations request. The role of the COG is to review the operational plan and assess any associated risks and benefits. The COG may approve a [**redacted**] or may defer approval to the CMG as appropriate. The Cyber Management Group (CMG) is a Director General (DG) level approval body that is formed [**redacted**] has been reviewed and recommended by the COG.

CSE then develops the [**relates to CSE operations**] is reviewed internally to ensure it aligns [**redacted**] and is later approved at the Director level, although CSE has indicated it could be subject to delegation to a Manager.

Findings and Recommendations

Clarity of Ministerial Authorizations

NSIRA set out to assess whether the requirements of the CSE Act in relation to ACO/DCOs are appropriately reflected in the MND’s MAs authorizing ACO/DCO activities, and that CSE appropriately consulted or received the consent of the MFA, as required by the Act.

NSIRA reviewed two MAs related to ACOs and DCOs, respectively, which were valid from [**redacted**]. Notably, both MAs only approved [**redacted**] ACO/DCOs. Additionally, NSIRA reviewed documentation supporting the MAs, including the Chief’s Applications to the MND and the associated confirmation letters from the MFA, as well as working- level documents and correspondence provided by both CSE and Global Affairs Canada (GAC).

The MAs examined by NSIRA outlined the new authorities found in the CSE Act, and set conditions on how ACO/DCOs are to be conducted, including the prohibitions that are found in the Act. Additionally, the MAs required that ACO/DCO activities align with Canada’s foreign policy priorities and respond to Canada’s national security, foreign, and defence policy priorities as articulated by the GC.

Supporting cyber operations with information collected under previous authorizations

CSE received its authority to conduct ACO/DCOs during a time when CSE’s collection of foreign signals intelligence (SIGINT) was authorized by MAs issued under the National Defence Act (NDA). [**redacted**]. CSE confirmed to NSIRA that the ACO/DCOs [**redacted**] relied solely on information collected under CSE Act MAs. CSE explained that [**redacted**] NSIRA will confirm this as part of our subsequent review of specific ACO/DCOs.

CSE’s consultation with the Minister of Foreign Affairs

CSE provided GAC with the full application packages for the ACO/DCO MAs in place during the review period. Further, GAC and CSE officials engaged at various levels prior to the coming into force of the CSE Act, and during the development of the MAs – particularly in assessing the classes of activities authorized within them. In response to CSE’s MA application package, the MFA provided letters acknowledging her consultation and consent on the DCO and ACO MAs respectively. NSIRA welcomes this early and rigorous engagement on the part of both departments, given the intersection of their respective mandates in the context of ACO/DCOs.

Both letters from the MFA note the utility of ACO/DCOs [**redacted**] for the GC, articulating the importance of approaching this capability with caution in the initial stages. Notably, the MFA highlights the “carefully defined” classes of activities defined in the ACO MA as assurance that the activities authorized under the MA presented [**redacted**]. Finally, the MFA directed her officials to work with CSE to establish a framework for collaboration on [**redacted**] This direction from the MFA aligns with GAC’s view of the importance of ensuring CSE’s activities would be coherent with Canada’s foreign policy, and that either the MA or another mechanism should provide for that.

Scope and breadth of the Ministerial Authorizations

[**relates to CSE operational policy**] ACO MA issued under section 31 of the CSE Act authorized classes of activities such as:

- [**redacted**] interfering with a target’s [**redacted**] or elements of the global information infrastructure (GII);

- [**redacted**]

- [**redacted**]

- disrupting a cyber threat actor’s ability to use certain infrastructure.

[**redacted**] DCO MA authorized the same activities, except for the last class of activities, [**relates to CSE operations**].

Both of the ACO/DCO MAs required CSE to conduct ACO/DCOs [**in a certain way**]. According to the ACO MA, it is these conditions, if met, that would make ACO/DCOs conducted under these MAs [**redacted**]. While GAC assesses While GAC assesses foreign policy risks at a more operational level, the MAs developed in the review period only required these two conditions to be met when conducting ACOs or DCOs. Further, the specifics of how to meet these broad conditions are left to CSE’s discretion, and the MA only requires CSE to self-report this. NSIRA further notes that these conditions do not include foreign policy variables, [**redacted**]. To confirm [**redacted**] foreign policy risk associated with an operation, NSIRA believes it is important that the MAs stipulate the calculation of foreign policy risk factors.

[**redacted**] stating that:

[**redacted**]

CSE appears to have responded to [**relates to CSE operations**]. This may also impact the Minisiter’s ability to assess any authorized activities as stipulated in the CSE Act, which requires sufficient precision in an MA application for the Minister to satisfy these requirements.

The classes of ACO/DCO activities, some of which are detailed in paragraph 27, are highly generalized. For instance, nearly any activity conducted in cyberspace can be feasibly classed as [**redacted**] interfering with elements of the global information infrastructure.” [**relates to CSE operations**]

Indeed, early discussions between CSE and GAC highlighted that the activity of [**redacted**] and content “raises difficult questions,” though NSIRA notes that such an activity is nevertheless authorized in the final ACO MA in the activity class of [**redacted**]. In short, the authorization for a class of activities [**redacted**] was incorporated into an even broader class of activities, without any evident [**redacted**] previously associated with it. This type of categorization does not sufficiently communicate information to the Minister to appreciate [**redacted**] activities that could be carried out under the MA.

By contrast, the techniques and associated examples outlined in the Applications are the only means through which it is clarified what types of activities could be taken as part of an ACO/DCO. These examples provide the basis for the MND to assess the classes of activities requested in the MA. Early correspondence between CSE and GAC saw the classes of activities described and analyzed in tandem with the techniques that would enable them. For instance, it was noted that [**relates to CSE operations**] which NSIRA found more informative with respect to what specific actions were captured within the class of activities. NSIRA further notes that even these techniques and examples are described in the Applications as a non-exhaustive list, potentially enabling CSE to conduct activities that are not clearly outlined in the Applications.

Similarly, the target of ACO/DCO activities is typically identified as ‘foreign actor,’ which could encompass a wide range of [**redacted**] In the early stages of MA development, CSE and GAC had discussed [**relates to CSE operations**] within the MAs, and GAC specified that the intent of [**redacted**] was to focus on [**redacted**] given the [**redacted**]. GAC also noted that the ACO MA “would [more] clearly define [**redacted**] to some extent. Neither of these considerations were reflected in the final [**redacted**] MAs, which CSE explained “are not limited to activities [**redacted**] meaning that [**redacted**]. NSIRA believes that the MAs should carefully define targets of ACO/DCO activities [**redacted**]. ACO/DCOs to specific target sets [**redacted**] to ensure that the activities permitted by the MA are reflective of its [**redacted**].

NSIRA notes that only the MAs, and not the associated Applications, authorize CSE to conduct its activities. As such, the exclusion of this information from the MAs means that only the broad classes of activities, as described in the MAs, guide the actions that CSE can take in conducting an ACO/DCO, and not the techniques and examples in the Applications that help justify the standard on which the risk of the activities is based. NSIRA does not believe that the classes of activities as described within the MAs sufficiently limit CSE’s activities [**relates to CSE operations**]. Even though, as explained by GAC, interdepartmental consultative processes between the two departments may serve as a mechanism to limit CSE’s activities, these processes were not explicitly recorded in the MAs authorizing them. NSIRA believes more precise ACO/DCO MAs will minimize the potential for any misunderstanding regarding the specific activities authorized.

The approach of specifying broad classes of activities is in line with CSE’s general practice of obtaining broad approvals from senior levels such as the Minister, with more specific internal controls guiding the operations to be conducted within the scope of the approved activity. According to GAC, it tends to rely on more specific approvals based on the [**redacted**] for which approval is sought. CSE offered that its approach allows CSE to obtain approval for activities in such a way that “enables flexibility to maximize opportunities, but with enough caveats to ensure risks are appropriately mitigated.”

While NSIRA acknowledges that MAs should be reasonably nimble to enable CSE to conduct [**redacted**]. ACO/DCOs should the need arise, it is important that CSE does not conduct activities that were not envisioned or authorized by either the MND or MFA in the issuance of the applicable MAs. NSIRA believes that in the context of [**redacted**] ACO/DCOs, CSE can adopt a more transparent approach that would make clearer the classes of activities it requests the Minister to authorize. This is especially important given the early stage of CSE’s use of these new authorities. By authorizing more precise classes of activities, associated techniques, and intended target sets ACO/DCOs would be less likely to [**redacted**] of the MAs.

CSE has stated that, “being clear about objectives is critical for demonstrating reasonableness and proportionality.” NSIRA shares this view, and believes that the classes of activities and the objectives described in the MAs and their associated Applications should be more explicit for the MND to be able to conclude on reasonableness and proportionality of ACO/DCOs – particularly given that the MAs assessed as part of this review were not specific to an operation. As part of the Authorization, the Minister also requires CSE to provide a quarterly retroactive report on the activities conducted. Moreover, to issue an authorization, the MND must be satisfied that the activities are reasonable and proportionate, and that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the objective of the cyber operation could not reasonably be achieved by other means. This requirement further points toward a need for the MND to appreciate, with a certain degree of specificity, the types of activities and objectives that will be carried out under the authorization.

In both of the MAs reviewed, the Minister concluded that the requirements set out within s. 34(4) of the CSE Act are met. Further, the MAs set out the objectives to be met in the conduct of ACO/DCOs. However, the rationale offered that the objectives could not be reasonably achieved by other means within the ACO MA is quite broad and focuses on general mitigation strategies for cyber threat activities. The paucity of detail provided to the Minister under the current framework could make it challenging for the MND to meet this legislative requirement. In relation to the thresholds of s. 34(4) of the CSE Act, CSE has indicated that “the application for the Authorization, must set out the facts that explain how each of the activities described in the Authorization are part of a larger set of individual activities or part of a class of activities that achieves an objectives that could not reasonably be achieved by other means.” In our subsequent review of ACO/DCOs, NSIRA will assess whether specific ACO/DCOs aligned with the objectives of the MA, and CSE’s determination that they could not have reasonably been achieved by other means.

Finding no. 1: The Active and Defensive Cyber Operations Ministerial Authorization Applications do not provide sufficient detail for the Minister(s) to appreciate the scope of the classes of activities being requested in the authorization. Similarly, the Ministerial Authorization does not sufficiently delineate precise classes of activities, associated techniques, and intended target sets to be employed in the conduct of operations.

Finding no. 2: The assessment of the foreign policy risks required by two conditions within the Active and Defensive Cyber Operations Ministerial Authorizations relies too much on technical attribution risks rather than characteristics that reflect Government of Canada’s foreign policy.

Recommendation no. 1: CSE should more precisely define the classes of activities, associated techniques, and intended target sets to be undertaken for Active and Defensive Cyber Operations as well as their underlying rationale and objectives, both in its Applications and associated Ministerial Authorizations for these activities.

Recommendation no. 2: GAC should include a mechanism to assess all relevant foreign policy risk parameters of Active and Defensive Cyber Operations within the associated Ministerial Authorizations.

[**redacted**] approach to MA application development

During the review period, CSE only developed MA applications for what it considered [**redacted**]. ACO/DCOs, which were first prioritized for development [**related to CSE operations**]. As CSE’s capacity to conduct ACO/DCOs matures and it begins to [**redacted**]. NSIRA has observed CSE and GAC exploring the idea of [**redacted**] ACOs, which, if pursued, would [**redacted**] based on GAC’s methodology.

While the MAs obtained to date, which are not specific to an operation, allow CSE to act in [**redacted**]. NSIRA believes their generalized nature is not transferable to [**potential MAs of a different nature**]. For instance, [**description of an NSIRA concern about the Minister’s ability to filly assess certain factors about cyber operations in a certain context**]. In the context of the development of the 2019-20 ACO MA Application, GAC noted, “other purposes would require other MAs. They will not be completely general; they will be specific to a context.

Further, under the current legislative scheme, the MA Applications are a key mechanism through which the MFA has an opportunity to assess ACO/DCO activities. Because of the [**redacted**] ACO/DCOs to Canada’s foreign policy and international relations, NSIRA believes the MFA should be more directly involved in their development and execution at the Ministerial level, in addition to the working level engagement that takes place between CSE and GAC. Both Ministers can more effectively take accountability for such operations through individual MAs that provide specific details relating to the operation, its rationale, and the activities, tools, and techniques that will enable it. As such, when CSE [**redacted**] ACOs, NSIRA encourages CSE to develop MA Applications that are specific to these operations, and ensure these documents contain all the pertinent operational details that would allow each Minister to fully assess the implications and risks of each cyber operation and take accountability for it.

Strategic direction for cyber operations

Section 19 of the CSE Act directs CSE’s authority to conduct ACOs in relation to international affairs, defence, or security, all areas that could implicate the responsibility of other departments. Additionally the MAs reviewed by NSIRA require that ACOs “align with Canada’s foreign policy and respond to national security, foreign, and defence policy priorities as articulated by the Government of Canada.” The setting of these priorities involve a wide range of GC departments, including the Privy Council Office (PCO), the Department of National Defence (DND), and Public Safety Canada (PS) – which are responsible for coordination and oversight of different parts of priority setting in this context. Throughout this governance review, it emerged that CSE confirms compliance with these requirements with a statement that the MA meets broader GC priorities with no elaboration of how these priorities are met.

Interdepartmental GC processes are not new in the context of coordinating national security activities and operations. As one example, when the MFA requires foreign intelligence collection within Canada, he or she submits a request to the Minister of Public Safety for this collection to be facilitated by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) in accordance with section 16 of the CSIS Act. A Committee consisting [**redacted**] subsequently considers this type of request. The Committee considers issues at the Assistant Deputy Minister level, [**relates to GC decision making processes**]. Similarly, ensuring an ACO’s alignment with broader priorities and that it could not reasonably be achieved by other means can also be confirmed through an interdepartmental process. In other words, interdepartmental consultations are a means to assess the objectives of ACOs, their alignment with broader GC priorities, as well as whether there are other means by which to achieve the set objectives, as required by the CSE Act.

The setting of broader GC priorities and objectives for ACOs emerged as a key component of the governance structure for this new power in early discussions between CSE and GAC. During the period of review, CSE developed ACOs with GAC participating in some aspects of the planning process. GAC encouraged the MFA to request the development of a governance mechanism to mitigate the risk that “CSE could decide, on their own, to engage [**redacted**] noting that [**redacted**].

Early internal GAC assessments contrast this with CSE’s foreign intelligence mandate, which responds to Cabinet-approved intelligence priorities, and captured the essence of this discrepancy in stating:

[**quotation from GAC that reflects discussion related to strategic objectives and priorities of cyber operations**]

In another instance, GAC described the setting of such priorities as an “important issue that has not yet been agreed to with CSE,” and explained its view at the time, that a body with a mandate relevant to the cyber operation should decide if it is the appropriate tool to achieve a particular objective. GAC explained that its officials eventually agreed to move forward without pursuing this matter as long as a governance mechanism was established with CSE.

In this context, s. 34(4) of the CSE Act requires that the objectives of the cyber operation could not be reasonably attained by other means, and that cyber operations respond to priorities in various subject areas. Given these requirements, NSIRA notes that GC departments, other than just CSE and GAC, may be able to provide meaningful insight regarding other options or ongoing activities that could achieve the same objectives.

Furthermore, GAC highlighted the fact that Cabinet sets the Standing Intelligence Requirements (SIRs) that limit and more narrowly direct CSE’s foreign intelligence collection activities. When asked about this issue, CSE responded that “these discussions led both GAC and CSE to agree to begin with a [**redacted**] Ministerial Authorization supported by the CSE-GAC ACO/DCO consultation structure and governance framework.”

In NSIRA’s view, the CSE Act and the ACO MA directly relate ACOs to broader GC objectives and priorities that directly implicate the mandates of departments such as DND, PCO, CSIS, and PS, in addition to those of CSE and GAC. It is not sufficient for CSE to state that an MA and its associated activities align with these priorities without elaboration or consultation of any other parties, given that Canada’s national security and defence policy priorities are under the remit or coordination of DND, PCO, and PS. These departments would be best positioned to comment on, and confirm, a specific ACO’s alignment with Canada’s goals in order to mitigate the potential risks associated with these operations and contribute to overall accountability of these operations.

[**relates to GC national security matters**] As such, the governance process merits the inclusion of – or at the very least consultation with – other departments whose mandates are to oversee Canada’s broader strategic objectives. This could ensure that Canada’s broader interests and any potential risks have been sufficiently considered and reflected in the development of ACOs.

Finding no. 3: The current governance framework does not include a mechanism to confirm an Active Cyber Operation’s (ACO) alignment with broader Government of Canada (GC) strategic priorities as required by the CSE Act and the Ministerial Authorization. While these objectives and priorities that are outside CSE and GAC’s remit alone, the two departments govern ACOs without input from the broader GC community involved in managing Canada’s overarching objectives.

Recommendation no. 3: CSE and GAC should establish a framework to consult key stakeholders, such as the National Security and Intelligence Advisor to the Prime Minister and other federal departments whose mandates intersect with proposed Active Cyber Operations to ensure that they align with broader Government of Canada strategic priorities and that the requirements of the CSE Act are satisfied.

Threshold for conducting pre-emptive DCOs

CSE differentiates between DCOs initiated in response to a cyber threat, and DCOs issued pre-emptively to prevent a cyber threat from manifesting. Further, CSE and GAC have discussed the nature of these operations, including that they exist on a spectrum ranging from operations which are responsive, to those which can be proactive in nature. Notably, in the case of DCOs, [**relates to CSE operations**].

CSE has explained that the initiation of a DCO “requires evidence of a threat that represents a source of harm to a federal institution or designated electronic information or information infrastructure.” In CSE’s view, this threat does not need to compromise the infrastructure before a DCO be initiated so long as evidence establishes a connection between the two.

At the same time, CSE has not yet developed a means to distinguish between this type of DCO and an ACO, given that discussions between GAC and CSE noted that a DCO could resemble an ACO when it is conducted proactively. Unlike ACOs, which require the consent of the MFA and result in a comprehensive engagement of GAC throughout the planning process, DCOs only require consultation with the MFA. Without a clear threshold for a proactive DCO, the potential exists for insufficient involvement of GAC in an operation that could resemble (or constitute) an ACO, [**redacted**].

In our subsequent review, we will pay close attention to the nature of any pre-emptive DCOs planned and/or conducted to ensure that they do not constitute an ACO.

Finding no. 4: CSE and GAC have not established a threshold to determine how to identify and differentiate between a pre-emptive Defensive Cyber Operation and an Active Cyber Operation, which can lead to the insufficient involvement of GAC if the operation is misclassified as defensive.

Recommendation no. 4: CSE and GAC should develop a threshold that discerns between an Active Cyber Operation and a pre-emptive Defensive Cyber Operation, and this threshold should be described to the Minister of National Defence within the applicable Ministerial Authorizations.

Collection of information as part of a cyber operation

Under s. 34(4) of the CSE Act, the MND only issues an authorization if he or she concludes that no information will be acquired under the authorization except in accordance with an authorization issued under ss. 26(1) or 27(1) or (2) or 40(1). The ACO/DCO MAs issued under the period of review reflect this restriction. The ACO/DCO MAs and corresponding applications only mention that existing foreign intelligence MAs will be used to acquire information to support ACO/DCO activities. It further articulates that no information will be acquired in the conduct of ACO/DCO activities which are authorized under the ACO MA.

However, the MAs and the supporting applications do not describe the full extent of information collection activities resulting from ACO/DCOs. According to CSE policy, CSE is still permitted to collect information [**redacted**] so long as this activity is covered under another existing MA. CSE explained that ACO/DCO MAs cannot be relied on to facilitate intelligence collection, however [**relates to CSE operations**]. For example, [**redacted**] using the applicable Foreign Intelligence (FI) authority to [**redacted**] in accordance with GC intelligence priorities.

Although the CSE Act permits CSE to acquire information pursuant to collection MAs, NSIRA believes that CSE’s policy to allow collection activities under different MAs during the conduct of cyber operations is not accurately expressed within the ACO/DCO MAs. Instead, the collection of information is listed under prohibited conduct within the ACO MA, giving the impression that collection cannot occur under any circumstances. As a result, NSIRA notes that the way in which the ACO MA is written does not provide full transparency of CSE’s own internal policies.

CSE explained that [**redacted**] during an ACO/DCO. Further, NSIRA learned from a CSE subject-matter expert (SME) that a specific [**redacted**] which outlines the precise activities to be undertaken as part of the operation, guides each ACO/DCO. [**relates to CSE operations**].

Given CSE’s policy of allowing collection and cyber operations to occur simultaneously [**redacted**]NSIRA will closely review the roles and responsibilities [**redacted**] involved in ACO/DCOs, as well as the technical aspects of using CSE’s systems in support of ACO/DCOs, in our subsequent review of specific operations conducted by CSE to date.

Finding no. 5: CSE’s internal policies regarding the collection of information in the conduct of cyber operations are not accurately described within the Active and Defensive Cyber Operations Ministerial Authorizations.

Recommendation no. 5: In its applications to the Minister of National Defence, CSE should accurately describe the potential for collection activities to occur under separate authorizations while engaging in Active and Defensive Cyber Operations.

Internal CSE Governance

NSIRA set out to assess whether CSE’s internal governance process sufficiently incorporates all the necessary considerations in the planning and execution of the operations and, whether those implicated in the conduct of ACO/DCOs (i.e. GAC and [**redacted**]) are adequately informed of the parameters and limitations pertaining to cyber operations.

During the period of review, CSE operationalized its requirements in the CSE Act and MAs through various internal planning and governance mechanisms. These ranged from strategic, high-level planning documents and mechanisms to the individual operational [**documents/mechanisms**] of each ACO/DCO.

Governance of operations

As described earlier, CSE uses various planning and governance documentation in the approval process for individual ACO/DCOs, including the [**redacted**] CSE first develops the [**redacted**] an ACO/DCO. Following this, CSE creates a [**redacted**] which outlines the risks to be considered in conducting the ACO/DCO. Additionally, the [**redacted**] and the [**redacted**] both generally include fields relating to the prohibitions set out within the CSE Act. Once a specific target is chosen, the [**redacted**] serves as the final governance document, prior to the [**redacted**] of an ACO/DCO.

Similar to the ACO/DCO MAs, as an initial operational plan, the [**redacted**] generally preapproves a set of activities and a generalized [**redacted**] which are then further refined and developed as part of the [**redacted**] process. In NSIRA’s view, [**relates to CSE operations**].

Specifically, the [**relates to CSE operations**] and other operational details that, in NSIRA’s view, surpass simply [**redacted**] and contain key components of operational planning. [**redacted**] details the specific [**redacted**]. Nonetheless, despite the [**redacted**] the [**redacted**] it may have a lower approval threshold than that of the [**redacted**].

Overall, NSIRA welcomes that CSE has developed procedures and documented its operational planning associated with ACO/DCO activities, in accordance with its requirements in the MPS. Nonetheless, the numerous governance documents that comprise the governance of ACO/DCOs exist to serve different audiences and purposes, and result in pertinent information dispersed across them, rather than being available in a unified structure for all implicated stakeholders and decision- makers to assess. NSIRA believes the many separate components of governance may be redundant and result in unnecessary ambiguity within the same operational plans that are meant to guide ACO/DCOs. Thus, NSIRA will assess the efficacy of this governance structure as it is applied to operations as part of our subsequent review.

Finding no. 6: The [**redacted**] process, which occurs after planning documents have been approved, contains information that is pertinent to CSE’s broader operational plans. The at [**redacted**] times contained pertinent information absent from these other documents, even though it is approved at a lower level of management.

Recommendation no. 6: CSE should include all pertinent information, including targeting and contextual information, within all operational plans in place for a cyber operation, and in materials it presents to GAC.

Training on the new framework for cyber operations

Both the ACO and DCO Ministerial Authorizations authorize the following classes of persons to conduct ACO/DCO activities: [**relates to CSE’s operational policy**]. The MAs further require that these “persons or classes of persons must operationally support CSE and Government of Canada intelligence requirements, and demonstrate an understanding of the relevant legal and policy requirements.”

Further demonstrating a commitment to the training and education of its operational staff of the new legal and policy requirements, CSE has stated—with respect to a specific operation—that:

The operational activities undertaken [**redacted**] who receive extensive and continuous training on their function and duties as well as the policy considerations and compliance requirements for their specific role. Additionally, [**redacted**] are trained and accountable for the activities they are carrying out, including all relevant compliance reporting requirements. [**redacted**] performing activities [**redacted**] are also provided, in advance, all related operational materials to ensure the operational conditions outlined within are understood and adhered to.

Finally, CSE explained to NSIRA that “prior to the new Act being approved, CSE provided virtual and in-person briefings on the new authorities to all of CSE’s workforce. More tailored briefings were available for operational teams.” These included presentations and question-and-answer sessions with the Deputy Chief, Policy and Communications and other briefing sessions created by CSE’s policy teams. However, NSIRA notes these types of training sessions, while educational at a high level, are not operation-specific and do not test employees understanding of their new legislative operating environment.

Based on the above requirements and assurances, NSIRA expected to find that CSE employees supporting ACO/DCOs were provided with sufficient and effective training to thoroughly understand their responsibilities in light of CSE’s new legal authorities and constraints, and to apply this knowledge in the delivery of ACO/DCOs.

In this context, CSE conducted a tabletop exercise with a view to introduce [**certain employees**] to the MA design process at an early stage, to enlist their involvement in the drafting of MAs, and to test the functional viability of the MA framework, among other objectives. Throughout the exercise, [**the above mentioned employee**] barred from seeking advice from policy and legal representatives for management to be able to observe results as they may naturally occur. NSIRA notes a key observation from the exercise:

[**redacted**] expressed unease with the need to rely on multiple MAs to support evolving mission objectives. Policy guidance and training will be needed to [**redacted**] to know what authority they are operating under as they proceed with an operation across missions and across MAs. This guidance and training must also account for the fact that information collected under different MAs could be subject to different data management requirements.

CSE stated that [**certain employees**] obtain knowledge of the legal authorities, requirements, and prohibitions of an ACO or DCO through planning meetings and knowledge of the operational documents. In an interview with a CSE SME [**redacted**] NSIRA learned that the training offered on CSE’s new legal authorities, requirements, and prohibitions [**redacted**]. The SME said that if they had any questions about the governance, they would [**relates to CSE operations**].

It is unclear to NSIRA whether there exists a requirement for [**redacted**] to thoroughly understand the parameters delineated for an ACO/DCO within the [**redacted**]. For instance, when asked about their comfort level of operating under different MAs [**redacted**] contained in the [**redacted**] CSE explained that [**redacted**] are developed from the [**redacted**], but as described [**redacted**]. NSIRA is concerned that if [**certain employees**] are focused primarily on the [**certain document/mechanism**] they may not have an adequate understanding of the broader parameters and restrictions associated with an operation.

The MAs authorizing ACO/DCOs impose a condition on CSE’s employees involved in the execution of ACO/DCOs to demonstrate an understanding of the legal and policy requirements under which they operate. The MAs and operational planning documents contain valuable information about the parameters of the broader authority to conduct ACO/DCOs and specific operations. As such, NSIRA believes it is imperative that employees working on any aspect of delivering an ACO/DCO receive thorough training sessions to familiarize them with the requirements and limitations of their respective operations set out in the [**redacted**] and [**redacted**]. Finally, [**certain employees**] could be tested on their understanding of the MAs and their constraints on specific operations.

Finding no. 7: CSE has provided its employees with high-level learning opportunities to learn about its new authorities to conduct Active and Defensive Cyber Operations (ACO/DCOs). However, employees working directly on ACO/DCOs may not have the requisite understanding of the specifics of CSE’s new legal authorities and parameters surrounding their use.

Recommendation no. 7: CSE should provide a structured training program to its employees involved in the execution of Active and Defensive Cyber Operations (ACO/DCOs), to ensure that they have the requisite knowledge of CSE’s legal authorities, requirements, and prohibitions, as required by the associated Ministerial Authorizations.

Framework for CSE’s Engagement with GAC

Given the legislative requirement for the MFA to provide consent or to be consulted in relation to ACO/DCOs, NSIRA set out to assess whether CSE developed a framework for effective consultation and engagement of GAC officials in the intersection of their respective mandates.

GAC’s assessment of foreign policy risks

In GAC and CSE’s engagement during the development of the consultation framework, they developed a mechanism by which GAC is to consent or be consulted on an operation, and to provide its assessment of the operation’s foreign policy risk. In response to a consultation request by CSE, GAC is responsible for providing, within five business days, a Foreign Policy Risk Assessment (FPRA) that confirms whether [**redacted**]. Notably, the FPRA does not constitute an approval of an operation, only a consultation. In order to inform the development of the FRPA, CSE prepares a tailored [**document/mechanism**] for GAC which summarizes aspects of the operation. In our subsequent review, NSIRA will analyse whether the timeline provided to GAC for specific operations enabled it to meaningfully assess the associated foreign policy risks.

For GAC, several factors affect whether or not an ACO/DCO [**redacted**] These factors include whether an ACO/DCO aligns with GAC’s position on international norms in cyberspace and the furtherance of Canada’s national interests, [**relates to GC national security matters**] This is reflected in the TORs for the CSE-GAC WG, which require GAC to assess:

- [**redacted**]

- Compliance with international law and cyber norms;

- Foreign Policy coherence, including whether the operation is in line with foreign policy, national security and defence priorities (i.e., beyond the [Standing Intelligence Requirements]); and

- [**redacted**]

In the context of the above assessment requirements, GAC explained to NSIRA that it conducts a less detailed assessment of the foreign policy risk of specific operations, through the FPRA, on the basis that it has conducted a more detailed assessment of the classes of activities authorized in the MA.106 This assessment approach is reflected in [**redacted**] FPRAs received by NSIRA, which concluded that the operations fall within [**redacted**] but did not elaborate on the factors listed above. Given that the FPRA provides assurance of [**redacted**] of specific operations and is required under the ACO MA, NSIRA will closely review these assessments as part our subsequent review of operations.

Compliance with international law and cyber norms

[**redacted**]

Parliament may authorize violations of international law, but must do so expressly. An example of this is following the decision in X (Re), 2014 FCA 249, Parliament amended the CSIS Act through the adoption of Bill C-44 in 2015. The new provisions made it explicitly clear that CSIS could perform its duties and functions within or outside of Canada and that, pursuant to the newly adopted provisions of the CSIS Act, a judge may authorize activities outside Canada to enable the Service to investigate a threat to the security of Canada “without regard to any other law.” As per the language of the CSE Act, ACO/DCO MAs may only authorize CSE to carry out ACO/DCO activities “despite any other Act of Parliament or of any foreign state.” As outlined by case law, this language may not be sufficiently clear to allow the Minister to authorize violations of customary international law.

[**redacted**] the MAs reviewed by NSIRA stated that the activities “will conform to Canada’s obligations under international law” and each MA required that CSE’s “activities will not contravene Canada’s obligations under international law.” This would indicate that all activities conducted under this MA would be compliant with international law. However, the governance documents developed by CSE and GAC, such as the CSE-GAC consultation framework, do not set out parameters for assessing ACO/DCO activities for compliance with Canada’s obligations under international law, nor is it made clear against which specific international legal obligations ACO/DCO activities are to be assessed. NSIRA will closely monitor how CSE and GAC consider compliance with international law in relation to ACO/DCO activities in the subsequent review.

In NSIRA’s engagement with GAC, GAC highlighted its interdepartmental and international consultations dating back to 2016 on the Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations (Tallinn Manual 2.0), which informed part of its development of the MAs [**redacted**]. GAC has created a Draft Desk book resulting from these consultations, which identifies Canada’s preliminary assessment of key rules of international law in cyberspace as described within the Tallinn Manual 2.0. NSIRA notes that while this analysis is a draft and does not represent Canada’s final position, it “has served as a starting point for further legal consideration.” NSIRA received no further documents that outline Canada’s understanding of how international law applies to ACO/DCO activities.

Further, documentation provided by both GAC and CSE recognizes a need to assess each potential ACO/DCO for lawfulness. GAC wrote that an analysis of the terms “acknowledged to be harmful” or “posing a threat to international peace and security” should be conducted within the context of each ACO/DCO. [**redacted**]

GAC explained that it assessed each activity within the authorized classes for compliance with international law at the MA development stage, and that consequently, a less detailed assessment of compliance with international law took place at the FPRA stage for each operation. GAC explained that the Draft Desk book and the Tallinn Manual 2.0 were consulted for these activities. From [**redacted**] FPRAs reviewed by NSIRA to date, it is not clear how the Draft Desk book or the analysis of the 2015 UN GGE voluntary norms has informed the assessment of each operation’s level of risk, or GAC’s conclusions that the ACO/DCOs complied with international law. Rather, GAC indicates that activities are compliant with international law, without an explanation of the basis behind these conclusions.

NSIRA notes that international law in cyberspace is a developing area, and recognizes that Canada and other States are continuing to develop and refine their legal analysis in this field. ACO/DCO activities conducted without a thorough and documented assessment of an operation’s compliance with international law would create significant legal risks for Canada if an operation violates international law. Ultimately, a better documented analysis of Canada’s legal obligations when conducting ACO/DCOs is necessary in order for GAC and CSE to assess an operation’s compliance with international law. NSIRA will further examine the lawfulness of ACO/DCO activities in our subsequent review.

Finding no. 8: CSE and GAC have not sufficiently developed a clear and objective framework with which to assess Canada’s obligations under international law in relation to Active and Defensive Cyber Operations.

Recommendation no. 8: CSE and GAC should provide an assessment of the international legal regime applicable to the conduct of Active and Defensive Cyber Operations. Additionally, CSE should require that GAC conduct and document a thorough legal assessment of each operation’s compliance with international law.

Bilateral communication of relevant information

Both GAC and CSE have implemented methodologies that require them to calculate risks based on certain factors. However, these types of risks are not absolute, and depend on a wide range of factors that can change over time or with the emergence of new information. In the case of GAC, those factors center around [**redacted**].

At present, CSE and GAC’s approach to accounting for any change in risks relies on GAC informing CSE if any change to Canada’s foreign policy should arise. However, based on GAC’s methodology above, the foreign policy risk of an operation may also rise if new information is uncovered about [**redacted**] or in relation to the potential impacts of the operation beyond a [**redacted**] For CSE’s part, it appears to primarily focus on changes to operational risks [**that are uncovered at a certain time or in a certain manner**]. This one-way mechanism does not account for other factors [**redacted**].

In this context, CSE has explained that an ACO/DCO is [**redacted**] and that as result, [**redacted**]. CSE further explained that DX and that subsequent activities may be adjusted as required using information obtained from the previous one. [**redacted**].

In this context, NSIRA observed operations that were planned to take place over a period of time, including a DCO where CSE would undertake [**related to CSE operations**]. Another ACO would see CSE [**redacted**]. In describing this operation to GAC, CSE wrote that activities would take place over a period of time [**redacted**].

[**related to CSE operations**] benefit from [**redacted**] of the ADO/DCOs [**redacted**]. NSIRA believes that a two-way notification mechanism triggering a re-assessment of the risks associated with an ACO/DCO should be established between CSE and GAC, whether those risks are uncovered prior to or during the course of an operation.

Finally, CSE’s internal governance process brings in GAC through [**a certain document/mechanism**]. In this context, GAC has highlighted objectives, [**redacted**] of an operation as information that CSE should provide for the purposes of assessing foreign policy risks. NSIRA has observed that the [**redacted**]. NSIRA notes that these details serve as important context to which GAC should have access as part of its assessment, particularly as GAC includes in its conclusions that the activities complied with [**redacted**].

Finding no. 9: CSE expects GAC to provide notification of any changes to foreign policy risks, but has not sufficiently considered the need to communicate other risks that may arise during an operation to GAC. Further, information critical to GAC’s assessment of foreign policy risks has also been excluded in materials CSE uses to engage GAC on an operation. As such, within the current consultation framework, CSE may not sufficiently communicate relevant information to GAC in support of its foreign policy assessment, and to manage ongoing changes in the risk associated with a cyber operation.

Recommendation no. 9: CSE and GAC should communicate to one another all relevant information and any new developments relevant to assessing risks associated with a cyber operation, both in the planning phases and during its execution.

Conclusion

This was NSIRA’s first review of CSE’s new powers to conduct ACO/DCOs, and it has illustrated CSE and GAC’s development of a governance structure for conducting these operations. CSE has now had the power to conduct these operations since 2019, though this review demonstrated that both departments begun conceptualizing a governance regime prior to the coming into force of the CSE Act. NSIRA is satisfied that CSE has, to date, developed a comprehensive governance structure, and commends its regular engagement with GAC to develop a consultation framework that sets out the roles and responsibilities of both departments.

However, at the broader governance level, CSE can improve the transparency and clarity around the planning of ACO/DCOs, particularly at this early stage, by setting out clearer parameters within the associated MAs for the classes of activities and target sets that could comprise ACO/DCOs. NSIRA further believes the continued development of cyber operations should benefit from consultation with other government departments responsible for Canada’s strategic priorities and objectives in the areas of national security and defence. Finally, CSE and GAC should develop a threshold and a definition for what constitutes a pre-emptive DCO, so as to ensure the appropriate involvement of GAC in an operation.

At the operational level, CSE and GAC should ensure that each operation’s compliance with international law is assessed and documented. On CSE’s part, it should ensure that information critical to assessing the risks of an operation be streamlined and included within all governance documents, and made available to all those involved in the development and approval of ACO/DCOs – including GAC. Finally, CSE should ensure that its operational staff are well-versed in the specifics of their new legislative framework and its applicability to specific operations.

While this review focused on the governance structures at play in relation to ACO/DCOs, of even greater importance is how these structures are implemented, and followed, in practice. We have made several observations about the information contained within the governance documents developed to date, and will subsequently assess how they are put into practice as part of our forthcoming review of ACO/DCOs.

Annex A: ACO/DCO Typologies

Figure 1: Different types of cyber operations. Source: CSE briefing materials

[**redacted figure**]

Figure 2: Difference between ACOs and DCOs. Source: CSE briefing material.

Text version of Figure 2

| DEFENSIVE CYBER OPERATIONS | ACTIVE CYBER OPERATIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| Authorized Activites |

|

|

| Ministerial Approval | MND approval with MFA consultation | MND approval with the consent or request of MFA |

| Intent | To take action online to protect electronic information and infrastructures of importance to the government of Canada | To degrade, disrupt, influence, respond to or interfere with capabilities of foreign individual, state, organization |

| Context | Initiated in response to a cyber threat, or proactively to prevent a cyber threat | Initiated in accordance with Ministerial direction as it relates to international affairs defence or security. |

| Threat Actor/Target Set | Conducted against threats linked to Government systems and systems of importance, irrespective of the actor **Once confirmed not against a Canadian, person in Canada, or on GII in Canada |

Conducted against specific targets in acordance with the Ministerial Authorization **Once confirmed not against a Canadian, person in Canada, or on GII in Canada |

| Outcome | Conducted with a view to stop or prevent cyber threats in a manner that is reasonable and proportionate to the intrusion or threat | Conducted to the extent directed by the Ministerial Authorization and that is reasonable and proportionate |

Annex B: ACO/DCOs (2019-2020)

[**redacted**]

Annex C: CSE-GAC Framework

| Interdepartmental Group | CSE-GAC Senior Management Team (SMT) | DG CSE-GAC ACO/DCO Working Group | ADM-Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-Chairs | SMT Co-Chairs: CSE DG, [**redacted**], GAC, DG Intelligence Bureau | Co-Chairs: CSE, DG [**redacted**] GAC,DG Intelligence Bureau. It iscomposed of some of the same DG-Level participants as the SMT as well as their working-level supports. | Co-Chairs: CSE, Deputy Chief, SIGINT GAC, ADM (Political Director) International Security |

| Roles and Responsibilities | Exchanges information on the departments’ respective plans and priorities, as well as areas of collaboration. | Under the auspices of the SMT, this entity was established with a mandate to collaborate specifically on ACO/DCO matters. Implementation of the governance framework associated with current and planned [**redacted**]. Coordinates information sharing related to the operational planning and execution of ACO/DCOs, as well as their associated risks and adherence to Canada’s foreign policy Collaborates on the renewal, evolution, and development of current and future MAs | Resolves any issues under the purview of the WG that cannot reach resolution at the DG-level. |

Annex D: Findings and Recommendations

Findings

Finding no. 1: The Active and Defensive Cyber Operations Ministerial Authorization Applications do not provide sufficient detail for the Minister(s) to appreciate the scope of the classes of activities being requested in the authorization. Similarly, the Ministerial Authorization does not sufficiently delineate precise classes of activities, associated techniques, and intended target sets to be employed in the conduct of operations.

Finding no. 2: The assessment of the foreign policy risks required by two conditions within the Active and Defensive Cyber Operations Ministerial Authorizations relies too much on technical attribution risks rather than characteristics that reflect Government of Canada’s foreign policy.

Finding no. 3: The current governance framework does not include a mechanism to confirm an Active Cyber Operation’s (ACO) alignment with broader Government of Canada (GC) strategic priorities as required by the CSE Act and the Ministerial Authorization. While these objectives and priorities that are outside CSE and GAC’s remit alone, the two departments govern ACOs without input from the broader GC community involved in managing Canada’s overarching objectives.

Finding no. 4: CSE and GAC have not established a threshold to determine how to identify and differentiate between a pre-emptive Defensive Cyber Operation and an Active Cyber Operation, which can lead to the insufficient involvement of GAC if the operation is misclassified as defensive.

Finding no. 5: CSE’s internal policies regarding the collection of information in the conduct of cyber operations are not accurately described within the Active and Defensive Cyber Operations Ministerial Authorizations.

Finding no. 6: The [**redacted**] process, which occurs after planning documents have been approved, contains information that is pertinent to CSE’s broader operational plans. The [**redacted**] at times contained pertinent information absent from these other documents, even though it is approved at a lower level of management.

Finding no. 7: CSE has provided its employees with high-level learning opportunities to learn about its new authorities to conduct Active and Defensive Cyber Operations (ACO/DCOs). However, employees working directly on ACO/DCOs may not have the requisite understanding of the specifics of CSE’s new legal authorities and parameters surrounding their use.

Finding no. 8: CSE and GAC have not sufficiently developed a clear and objective framework with which to assess Canada’s obligations under international law in relation to Active and Defensive Cyber Operations.

Finding no. 9: CSE expects GAC to provide notification of any changes to foreign policy risks, but has not sufficiently considered the need to communicate other risks that may arise during an operation to GAC. Further, information critical to GAC’s assessment of foreign policy risks has also been excluded in materials CSE uses to engage GAC on an operation. As such, within the current consultation framework, CSE may not sufficiently communicate relevant information to GAC in support of its foreign policy assessment, and to manage ongoing changes in the risk associated with a cyber operation.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1: CSE should more precisely define the classes of activities, associated techniques, and intended target sets to be undertaken for Active and Defensive Cyber Operations as well as their underlying rationale and objectives, both in its Applications and associated Ministerial Authorizations for these activities.

Recommendation no. 2: GAC should include a mechanism to assess all relevant foreign policy risk parameters of Active and Defensive Cyber Operations within the associated Ministerial Authorizations.

Recommendation no. 3: CSE and GAC should establish a framework to consult key stakeholders, such as the National Security and Intelligence Advisor to the Prime Minister and other federal departments whose mandates intersect with proposed Active Cyber Operations, to ensure that they align with broader Government of Canada strategic priorities and that the requirements of the CSE Act are satisfied.

Recommendation no. 4: CSE and GAC should develop a threshold that discerns between an Active Cyber Operation and a pre-emptive Defensive Cyber Operation, and this threshold should be described to the Minister of National Defence within the applicable Ministerial Authorizations.

Recommendation no. 5: In its applications to the Minister of National Defence, CSE should accurately describe the potential for collection activities to occur under separate authorizations while engaging in Active and Defensive Cyber Operations.

Recommendation no. 6: CSE should include all pertinent information, including targeting and contextual information, within all operational plans in place for a cyber operation, and in materials it presents to GAC.

Recommendation no. 7: CSE should provide a structured training program to its employees involved in the execution of Active and Defensive Cyber Operations (ACO/DCOs), to ensure that they have the requisite knowledge of CSE’s legal authorities, requirements, and prohibitions, as required by the associated Ministerial Authorizations.

Recommendation no. 8: CSE and GAC should provide an assessment of the international legal regime applicable to the conduct of Active and Defensive Cyber Operations. Additionally, CSE should require that GAC conduct and document a thorough legal assessment of each operation’s compliance with international law.

Recommendation no. 9: CSE and GAC should communicate to one another all relevant information and any new developments relevant to assessing risks associated with a cyber operation, both in the planning phases and during its execution.