Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

23-12

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

23-12

ISSN: 2817-7525

This report presents findings and recommendations made in NSIRA’s annual review of disclosures of information under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act (SCIDA). It was tabled in Parliament by the Minister of Public Safety, as required under subsection 39(2) of the NSIRA Act, on November 1st, 2023.

The SCIDA provides an explicit, stand-alone authority to disclose information between Government of Canada institutions in order to protect Canada against activities that undermine its security. Its stated purpose is to encourage and facilitate such disclosures.

This report provides an overview of the SCIDA’s use in 2022. In doing so, it:

The report contains six recommendations designed to increase standardization across the Government of Canada in a manner that is consistent with institutions’ demonstrated best practices and the SCIDA’s guiding principles.

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

23-08

Date of Publishing:

This quarterly report has been prepared by management as required by section 65.1 of the Financial Administration Act and in the form and manner prescribed by the Directive on Accounting Standards, GC 4400 Departmental Quarterly Financial Report. This quarterly financial report should be read in conjunction with the 2024–2025 Main Estimates.

This quarterly report has not been subject to an external audit or review.

The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) is an independent external review body that reports to Parliament. Established in July 2019, NSIRA is responsible for conducting reviews of the Government of Canada’s national security and intelligence activities to ensure that they are lawful, reasonable and necessary. NSIRA also hears public complaints regarding key national security agencies and their activities.

The NSIRA Secretariat supports the Agency in the delivery of its mandate. Independent scrutiny contributes to strengthening the accountability framework for national security and intelligence activities and to enhancing public confidence. Ministers and Canadians are informed whether national security and intelligence activities undertaken by Government of Canada institutions are lawful, reasonable, and necessary

A summary description NSIRA’s program activities can be found in Part II of the Main Estimates. Information on NSIRA’s mandate can be found on its website.

This quarterly report has been prepared by management using an expenditure basis of accounting. The accompanying Statement of Authorities includes the agency’s spending authorities granted by Parliament and those used by the agency, consistent with the 2024–2025 Main Estimates. This quarterly report has been prepared using a special-purpose financial reporting framework (cash basis) designed to meet financial information needs with respect to the use of spending authorities.

The authority of Parliament is required before money can be spent by the government. Approvals are given in the form of annually approved limits through appropriation acts or through legislation in the form of statutory spending authorities for specific purposes.

The Department uses the full accrual method of accounting to prepare and present its annual departmental financial statements that are part of the departmental results reporting process. However, the spending authorities voted by Parliament remain on an expenditure basis.

This section highlights the significant items that contributed to the net increase or decrease in authorities available for the year and actual expenditures for the quarter ended September 30, 2024.

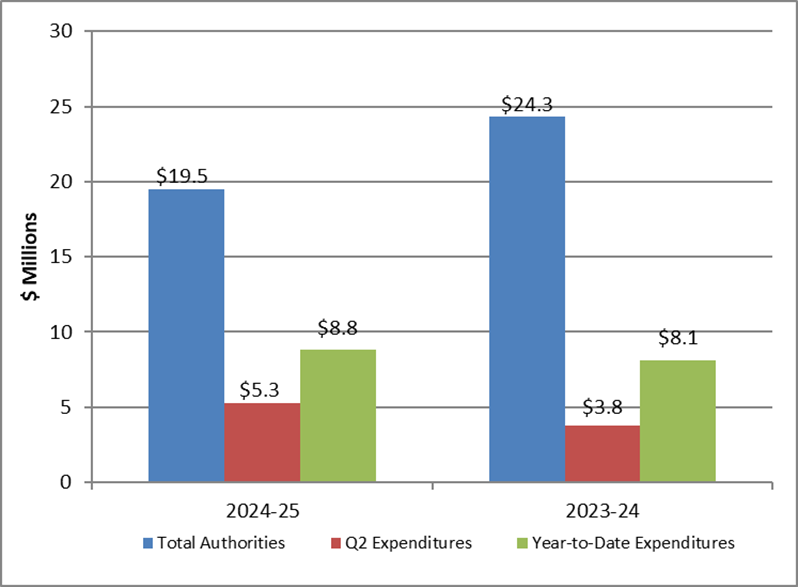

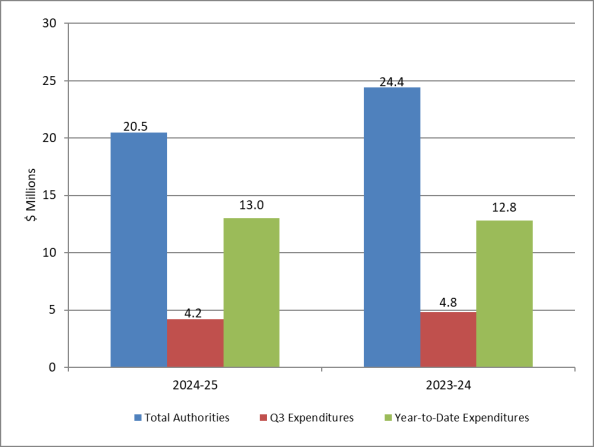

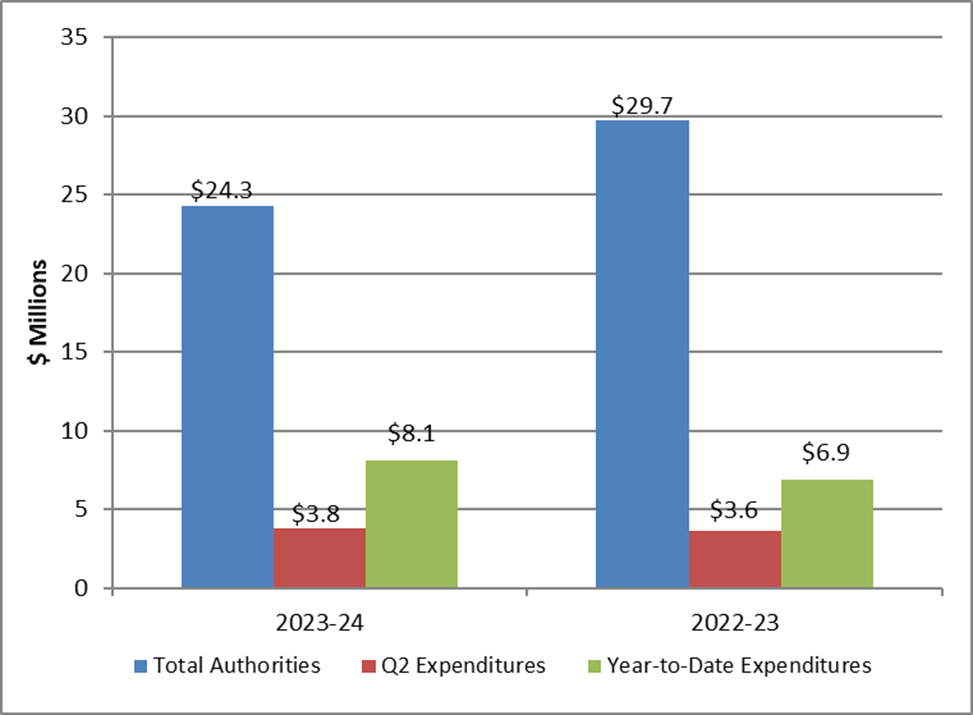

NSIRA Secretariat spent approximately 45% of its authorities by the end of the second quarter, compared with 33% in the same quarter of 2023–2024 (see graph 1).

| 2024-25 | 2023-24 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Authorities | $19.5 | $24.3 |

| Q2 Expenditures | $5.3 | $3.8 |

| Year-to-Date Expenditures | $8.8 | $8.1 |

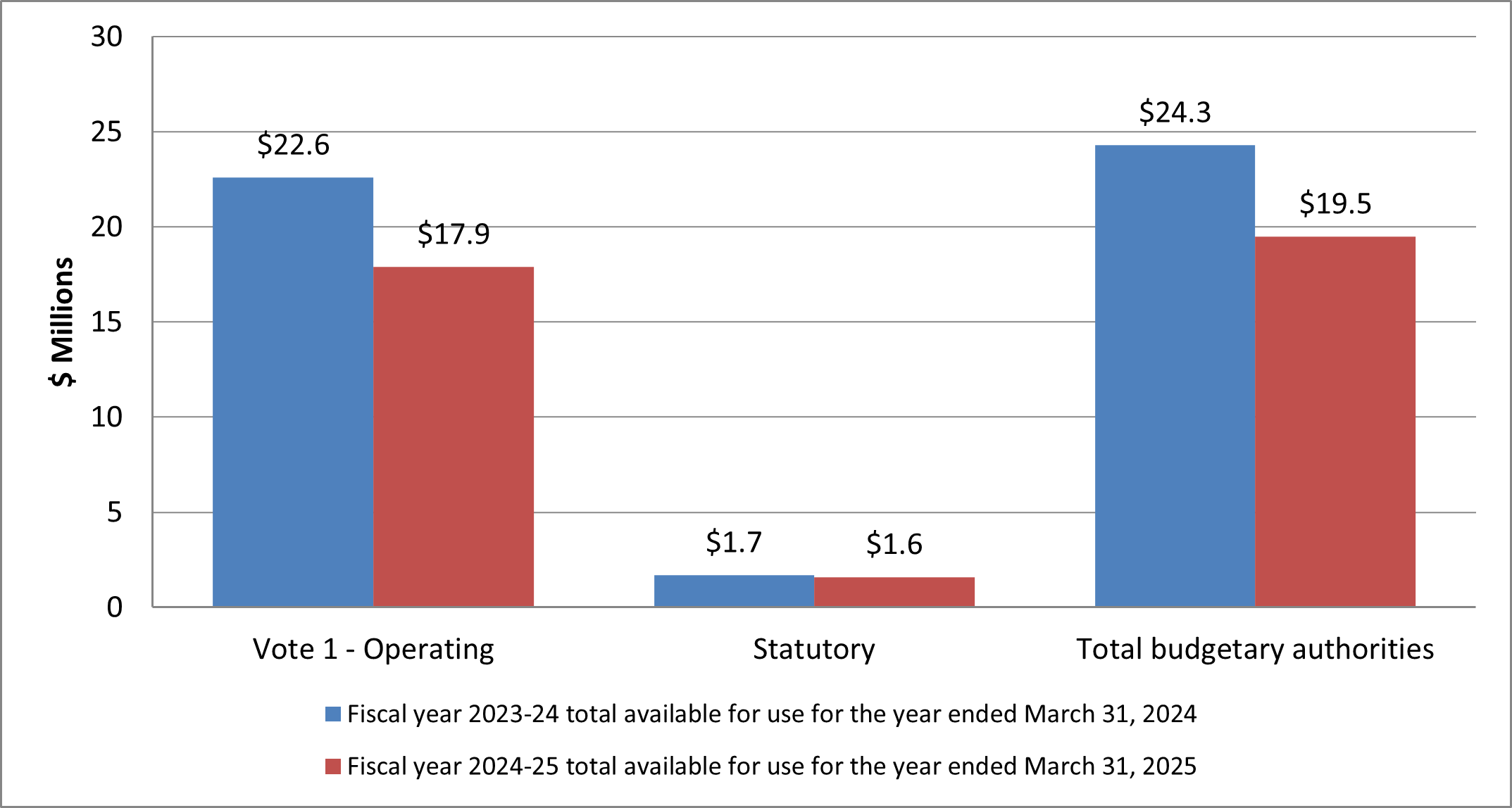

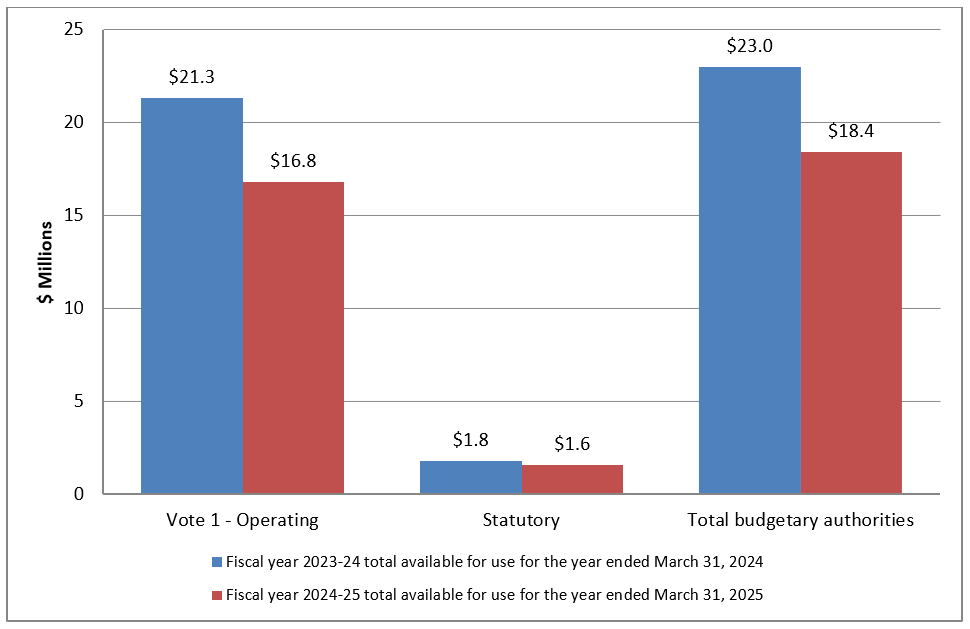

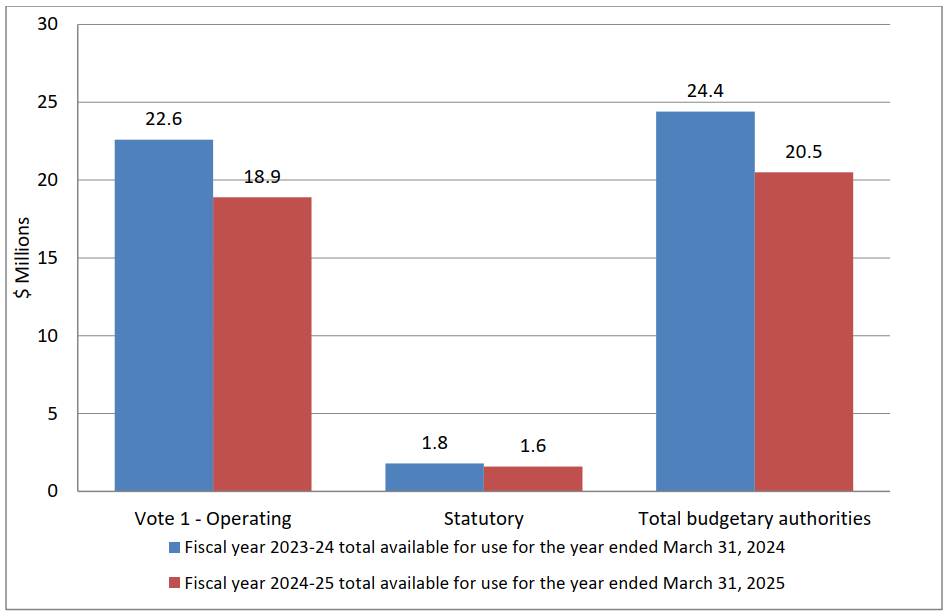

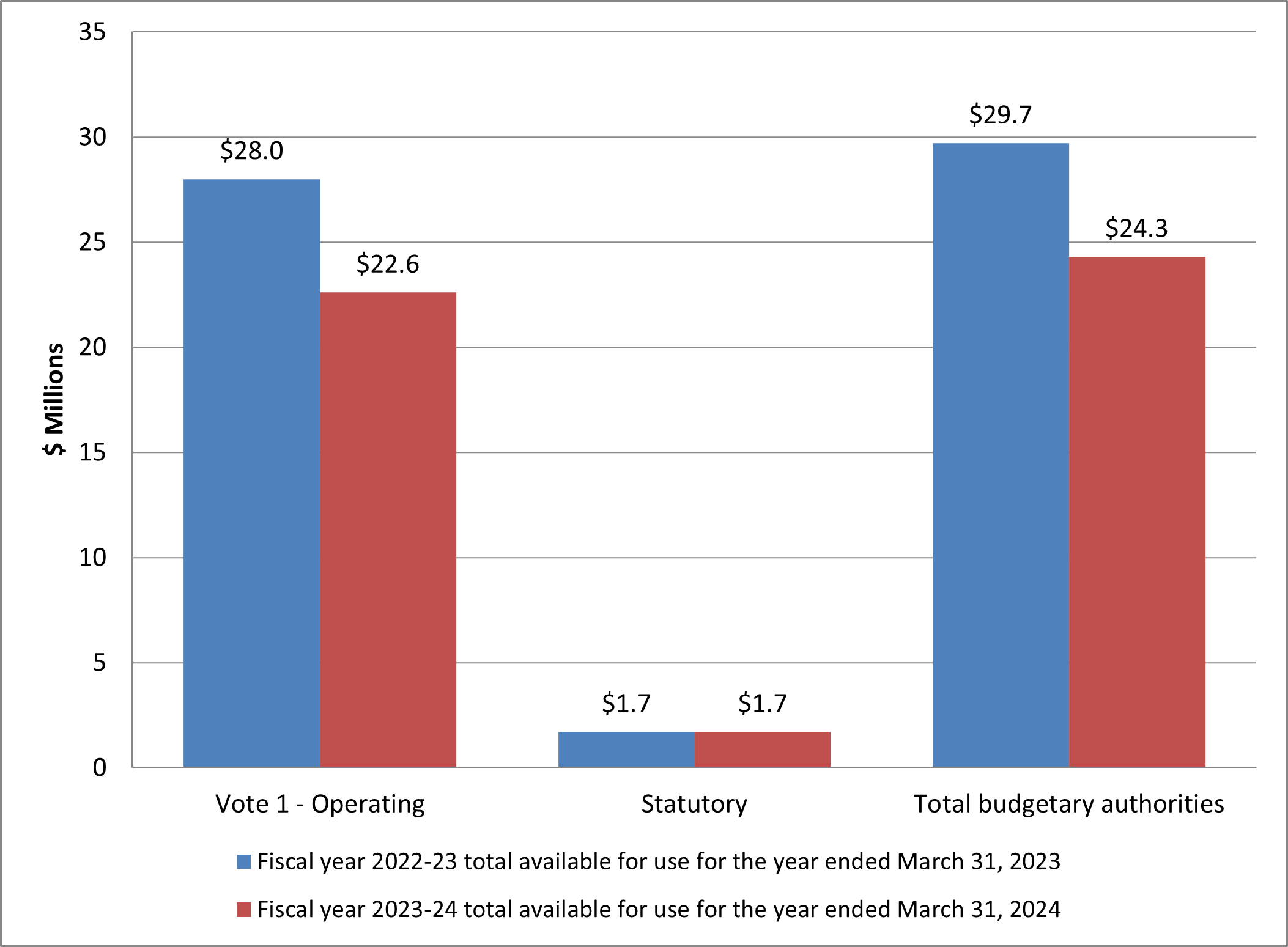

As of September 30, 2024, Parliament had approved $19.5 million in total authorities for use by NSIRA Secretariat for 2024–2025 compared with $24.3 million as of September 30, 2023, for a net decrease of $4.8 million or 19.8% (see graph 2).

| Fiscal year 2023-24 total available for use for the year ended March 31, 2024 | Fiscal year 2024-25 total available for use for the year ended March 31, 2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| Vote 1 – Operating | 22.6 | 17.9 |

| Statutory | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Total budgetary authorities | 24.3 | 19.5 |

*Details may not sum to totals due to rounding*

The decrease of $4.8 million in authorities is mostly explained by a reduction in capital funding for infrastructure projects due to the fact that they have reached completion in this fiscal year.

The second quarter expenditures totalled $5.3 million for an increase of $1.5 million when compared with $3.8 million spent during the same period in 2023–2024. Table 1 presents budgetary expenditures by standard object.

| Variances in expenditures by standard object (in thousands of dollars) | Fiscal year 2024–25: expended during the quarter ended September 30, 2024 | Fiscal year 2023–24: expended during the quarter ended September 30, 2023 | Variance $ | Variance % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel | 3,856 | 3,014 | 842 | 28% |

| Transportation and communications | 77 | 62 | 15 | 24% |

| Information | 7 | 4 | 3 | 75% |

| Professional and special services | 1,320 | 504 | 816 | 162% |

| Rentals | 17 | 25 | (8) | (32%) |

| Repair and maintenance | 37 | 3 | 34 | 1133% |

| Utilities, materials, and supplies | 12 | 50 | (38) | (76%) |

| Acquisition of machinery and equipment | 8 | 4 | 4 | 100% |

| Other subsidies and payments | (38) | 118 | (156) | (132%) |

| Total gross budgetary expenditures | 5,296 | 3,784 | 1,512 | 40% |

The increase of $842,000 reflects management’s decision to increase FTEs to enhance operational capacity in response to greater demand for output. It is also a result of an increase in average salary due to alignment with increases approved as part of collective bargaining.

The increase of $816,000 is mainly explained by a change in the timing of the billing for maintenance and services in support of our classified IT network infrastructure.

The increase of $34,000 is explained by some one-time office repairs in fiscal year 2024-2025.

The decrease of $38,000 is explained by temporarily unreconciled acquisition card purchases in fiscal year 2023-2024.

The decrease of $156,000 is explained by an increase in the recovery of salary overpayments.

The year-to-date expenditures totalled $8.8 million for an increase of $0.7 million (8%) when compared with $8.1 million spent during the same period in 2023-2024. Table 2 presents budgetary expenditures by standard object.

| Variances in expenditures by standard object (in thousands of dollars) | Fiscal year 2024–25: year-to-date expenditures as of September 30, 2024 | Fiscal year 2023–24: year-to-date expenditures as of September 30, 2023 | Variance $ | Variance % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel | 6,864 | 5,900 | 964 | 16% |

| Transportation and communications | 135 | 192 | (57) | (30%) |

| Information | 13 | 4 | 9 | 225% |

| Professional and special services | 1,589 | 1,669 | (80) | (5%) |

| Rentals | 42 | 73 | (31) | (42%) |

| Repair and maintenance | 40 | 27 | 13 | 48% |

| Utilities, materials and supplies | 40 | 57 | (17) | (30%) |

| Acquisition of machinery and equipment | 20 | 52 | (32) | (62%) |

| Other subsidies and payments | 41 | 122 | (81) | (66%) |

| Total gross budgetary expenditures | 8,784 | 8,096 | 688 | 8% |

The decrease of $57,000 is due to the timing of invoicing for the organization’s Network Services.

The increase of $9,000 is due to the timing of invoicing for printing services.

The decrease of $32,000 is mainly explained by the one-time purchase of a specialized laptop in 2023-2024.

The decrease of $81,000 is mainly explained by higher leasehold improvement amortization expenses in 2023-2024.

There is a risk that the funding received to offset pay increases will be insufficient to cover the costs of such increases and the year-over-year cost of services provided by other government departments/agencies is increasing significantly. To mitigate, NSIRA Secretariat is forecasting both personnel and operating expenditures three fiscal years out and identifying critical functions.

NSIRA Secretariat is closely monitoring pay transactions to identify and address over and under payments in a timely manner. It continues to apply ongoing mitigating controls such as participating in PSPC’s Reconciliation Tool (RT) initiative.

Mitigation measures for the risks outlined above have been identified and are factored into NSIRA Secretariat’s approach and timelines for the execution of its mandated activities.

Mr. Charles Fugère was appointed by the Governor-in-Council to be Executive Director of the NSIRA Secretariat, for a period of three years, on July 27, 2024.

Charles Fugère

Executive Director

Martyn Turcotte

Chief Financial Officer

(in thousands of dollars)

| Fiscal year 2024–25 | Fiscal year 2023–24 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total available for use for the year ending March 31, 2025 (note 1) | Used during the quarter ended September 30, 2024 | Year to date used at quarter-end | Total available for use for the year ending March 31, 2024 (note 1) | Used during the quarter ended September 30, 2023 | Year to date used at quarter-end | |

| Vote 1 – Net operating expenditures | 17,857 | 4,895 | 7,983 | 22,564 | 3,345 | 7,218 |

| Budgetary statutory authorities | ||||||

| Contributions to employee benefit plans | 1,601 | 401 | 801 | 1,755 | 439 | 878 |

| Total budgetary authorities (note 2) | 19,458 | 5,296 | 8,784 | 24,319 | 3,784 | 8,096 |

Note 1: Includes only authorities available for use and granted by Parliament as at quarter-end.

Note 2: Details may not sum to totals due to rounding.

(in thousands of dollars)

| Fiscal year 2024–25 | Fiscal year 2023–24 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned expenditures for the year ending March 31, 2025 (note 1) | Expended during the quarter ended September 30, 2024 | Year-to-date used at quarter-end | Planned expenditures for the year ending March 31, 2024 | Expended during the quarter ended September 30, 2023 | Year-to-date used at quarter-end | |

| Expenditures | ||||||

| Personnel | 13,205 | 3,856 | 6,864 | 13,303 | 3,014 | 5,900 |

| Transportation and communications | 685 | 77 | 135 | 650 | 62 | 192 |

| Information | 76 | 7 | 13 | 371 | 4 | 4 |

| Professional and special services | 4,624 | 1,320 | 1,589 | 4,906 | 504 | 1,669 |

| Rentals | 309 | 17 | 42 | 271 | 25 | 73 |

| Repair and maintenance | 436 | 37 | 40 | 4,580 | 3 | 27 |

| Utilities, materials, and supplies | 58 | 12 | 40 | 73 | 50 | 57 |

| Acquisition of machinery and equipment | 65 | 8 | 20 | 132 | 4 | 52 |

| Other subsidies and payments | 0 | (38) | 41 | 33 | 118 | 122 |

| Total gross budgetary expenditures (note 2) |

19,458 | 5,296 | 8,784 | 24,319 | 3,784 | 8,096 |

Note 1: Includes only authorities available for use and granted by Parliament as at quarter-end.

Note 2: Details may not sum to totals due to rounding.

Ottawa, Ontario, November 6, 2024 – The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency’s (NSIRA) fifth annual report has been tabled in Parliament.

This report provides an overview and discussion of NSIRA’s review and investigation work throughout 2023, including its findings and recommendations. It highlights the significant outcomes achieved through strengthened partnerships and an unwavering commitment to all Canadians to provide accountability and transparency regarding the Government of Canada’s national security and intelligence activities.

The annual report also reflects on a major milestone: NSIRA’s five-year anniversary. The agency has matured since its inception in 2019, keeping pace with emerging threats, technological advancements, and evolving security and intelligence activities. In stride, NSIRA has built an enhanced capacity to address complex issues and conduct thorough and effective reviews and investigations with a team of dedicated professionals with diverse expertise.

In 2023, in addition to its mandatory reviews, NSIRA continued executing discretionary reviews that were deemed relevant and appropriate. Of the ongoing reviews in 2023, NSIRA has since completed 12. In particular, NSIRA’s review on the Dissemination of Intelligence on People’s Republic of China Political Foreign Interference, 2018–2023 was a significant achievement. NSIRA evaluated the flow of intelligence within government from the collectors to consumers, including senior public servants and elected officials. This involved scrutinizing internal processes regarding how collected information was shared and escalated to relevant decision-makers. NSIRA determined it was in the public interest to report on this matter and produced its first special report under section 40 of the NSIRA Act, which was tabled in both houses of Parliament in May 2024.

Review highlights in the report include the following:

NSIRA also closed 12 investigations in 2023. Last year, the agency saw an increase in complaints against CSIS under section 16 of the NSIRA Act, alleging process delays in immigration or citizenship security screening.

This annual report demonstrates the value of expanded partnerships and how the organization leveraged its network of international oversight partners in 2023, including lessons learned and shared. NSIRA’s integration into the global community of national security and intelligence oversight has advanced the agency’s development and enhanced its capacity to carry out its mandate.

Over the past five years, NSIRA has sought to demystify the often-opaque domain of national security and intelligence agencies and empower Canadians to participate in informed discussions about their security and rights. Recently, the agency codified its approach by formalizing its vision, mission, and values statements.

Looking ahead, NSIRA is committed to continuing its vital work reporting on whether national security or intelligence activities are respectful of the rights and freedoms of all Canadians and enhancing public awareness and understanding of the critical issues at stake in national security and intelligence.

Date of Publishing:

As members of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA), we are pleased to present our 2023 Annual Report, marking the five-year milestone of our agency’s journey. This report encapsulates our activities of the past year and provides an opportunity for reflection on the progress and evolution of our agency since 2019.

As world events have unfolded, and the pace of security and intelligence activities has advanced, the presence of our agency has never been more important. Since NSIRA’s inception, our mandate has been to provide independent oversight and accountability of Canada’s national security and intelligence activities. Over the last five years, we have brought greater transparency on such activities to the Canadian public, and we are proud of the strides we have made in fulfilling this crucial role.

Our agency has matured and strengthened in many ways. We have built enhanced capacity to conduct thorough and effective reviews and investigations of our country’s diverse range of national security and intelligence activities. We have assembled a team of dedicated professionals with a wealth of expertise in numerous fields, enabling us to address complex issues and provide informed assessments and recommendations.

We have also fostered constructive relationships with our reviewees, partner agencies, parliamentary committees, and civil society organizations. These partnerships have been instrumental in facilitating our access to information, engagement in meaningful dialogue, and our ability to promote transparency and accountability.

Over the last five years, we have enhanced public awareness and understanding of the critical issues at stake in the realm of national security and intelligence. Through the publication of our reports, we have sought to demystify this often-opaque domain and empower Canadians to participate in informed discussions about their security and rights.

As we reflect on our achievements to date, we are mindful of the challenges that lie ahead. The landscape of national security and intelligence is constantly evolving as emerging threats and technological advancements present new challenges. As adaptive and agile responses are required by Canada’s security and intelligence agencies, NSIRA will continue to assess whether such responses are lawful, reasonable, and necessary.

Looking ahead, we are committed to continuing our vital work. We remain dedicated and vigilant in our role of ensuring that Canada’s national security and intelligence framework remains accountable, and reporting on whether national security or intelligence activities are respectful of the rights and freedoms of all Canadians.

We extend our gratitude to all Secretariat staff, past and present, whose dedication and support has contributed to NSIRA’s evolution over the past five years. Their efforts have been invaluable in shaping our agency and our work serving the Canadian public.

Marie Deschamps

Marie-Lucie Morin

Foluke Laosebikan

Jim Chu

Craig Forcese

Matthew Cassar

Colleen Swords

2023 marked a momentous year for the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA). Relentless efforts to mature the agency’s processes and professionalize its approaches allowed NSIRA to conduct its reviews and investigations to the highest standards. This report highlights the significant outcomes achieved through refined methodologies, strengthened partnerships, and an unwavering commitment to all Canadians to provide accountability and transparency of the national security and intelligence activities of the Government of Canada.

NSIRA celebrated its fifth anniversary in July 2024 and has used this as an opportunity to reflect on its growth and development, as well as lessons learned. The agency has embraced its broad and unique mandate, completing reviews that span organizations and increasing its transparency in implementing its investigations mandate. NSIRA has prioritized the growth and development of its staff, enhanced review literacy across reviewed entities, and continued to maintain best practices and the highest standards in implementing its mandate.

NSIRA has expanded and leveraged its network of oversight partners through its numerous engagements with international counterparts and participation in international forums in 2023. This has benefitted all parties through sharing best practices, lessons learned, expertise, and research. NSIRA’s integration into the international community of national security and intelligence oversight has advanced the agency’s development and enhanced its capacity to carry out its mandate.

The following are highlights and key outcomes of the reviews NSIRA completed in 2023. (Ongoing reviews are not included.) Annex B lists all the findings and recommendations associated with reviews completed in 2023.

NSIRA completed the following reviews where Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) activities were solely at issue:

NSIRA completed the following reviews where Communications Security Establishment (CSE) activities were mostly at issue:

NSIRA completed a review of the Canada Border Services Agency’s (CBSA’s) Confidential Human Source (CHS) program, which examined the legal and policy frameworks governing the program, with particular attention to the management and assessment of risk; the agency’s discharge of its duty of care to its sources; and the sufficiency of ministerial direction and accountability in relation to the program.

NSIRA completed a review of the Department of National Defence (DND) and Canadian Armed Forces’ (CAFs) Human Source Handling program, which examined whether DND/CAF conducts its human source-handling activities lawfully, ethically, and with appropriate accountability.

NSIRA completed a review of the operational collaboration between CSE and CSIS, which was NSIRA’s first review to examine the effectiveness of the collaboration by assessing their respective mandates and associated prohibitions. This review also satisfied NSIRA’s annual requirement under section 8(2) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act (NSIRA Act) to review an aspect of CSIS’ threat reduction measures (TRMs).

NSIRA completed two mandated multi-departmental reviews in 2023:

The NSIRA Secretariat – in consultation with NSIRA members – established service standards for complaint investigations and set the goal of completing 90 percent of cases within the service standards. This commitment supports NSIRA’s complaint investigations by ensuring timeliness. NSIRA also implemented an independent verification process for complaints against CSE. Additionally, the agency completed a study on the collection of race-based data and other demographic information.

NSIRA observed an increase of complaints against CSIS, pursuant to section 16 of the NSIRA Act, alleging process delays in immigration or citizenship security screening.

The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) is an independent agency that reports to Parliament and has the authority to conduct an integrated review of Government of Canada national security and intelligence activities. This provides Canada with one of the most extensive systems for independent review of national security in the world. NSIRA has a dual mandate: to conduct reviews, and to carry out investigations, of complaints related to Canada’s national security or intelligence activities. In fulfilling its mandate, the agency is assisted by a Secretariat headed by an Executive Director.

NSIRA’s review mandate is broad, as outlined in subsection 8(1) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act (NSIRA Act). This mandate includes reviewing the activities of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), as well as those of any other federal department or agency that are related to national security or intelligence. The agency may also review any national security or intelligence matter that a Minister of the Crown refers to NSIRA.

NSIRA is responsible for investigating complaints related to national security or intelligence. This is outlined in paragraph 8(1)(d) of the NSIRA Act, and involves investigating the following:

The conversation on national security and intelligence issues is evolving in Canada. In recent years, armed conflicts, the COVID-19 pandemic, and activities of foreign and domestic security and intelligence agencies have all been featured in news headlines. Most recently, Parliament debated the role of Canada’s security and intelligence agencies in responding to the threat of foreign political interference. The importance of robust review and oversight has never been more clear or timely. As the conversation grows, Canadians will want more information about the functioning of their security and intelligence systems. NSIRA is the trusted eyes and ears of Canadians, providing transparency that did not previously exist.

NSIRA’s mandate is to review issues and conduct investigations of complaints related to Canada’s national security or intelligence activities. Prior to NSIRA, although some activities were subject to review, no single agency had the mandate and authority to review activities across the national security and intelligence landscape, and some departments lacked an independent review body.

The siloed framework limited NSIRA’s predecessor agencies, the Security and Intelligence Review Committee (SIRC) and the Office of the Communications Security Establishment Commissioner to reviews and investigations of complaints within their narrow mandates. For example, reviews did not trace the progression of an issue as it traversed government departments.

NSIRA’s broad mandate is unique within the international community, providing a much greater understanding of how departments and agencies work and interact in the national security and intelligence space. For example, in 2023, NSIRA launched a review of the dissemination of intelligence on foreign interference, focusing on how intelligence progressed from departments charged with collecting intelligence through to its ultimate consumers. Such a review was not possible for NSIRA’s siloed predecessors.

NSIRA’s reviews have involved 19 departments and agencies to date. Its expanded mandate for investigating complaints encompasses those against CSIS, CSE and, upon referral, those from the CRCC concerning the RCMP and the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC). NSIRA’s work gets to the heart of how national security and intelligence activities are conducted, allowing for precise and effective recommendations.

NSIRA has prioritized professionalizing how it conducts reviews by developing policies and processes to support the review process. These were created even as the agency was growing and delivering on its complex mandate, and through the COVID-19 pandemic.

NSIRA has also modernized its policies and processes for its investigations of complaints. The agency undertook significant reform of its investigative process and published new Rules of Procedure to replace the previous model, increasing procedural transparency for those involved in the complaints process. When the COVID-19 pandemic made in-person hearings impossible, NSIRA pivoted and introduced alternate solutions, such as conducting its investigative interviews over video conference, thereby retaining access for participants.

NSIRA has built a proactive disclosure practice to publish its reports on its website. It has also undertaken an effort to publish those prepared by SIRC, to the greatest extent possible. The goal is to make NSIRA’s reviews and its findings and recommendations available to the public as soon as possible. Proactive disclosure increases transparency and contributes to the dialogue on national security and intelligence in Canada.

The Secretariat is now staffed by almost 100 full-time employees. NSIRA’s greatest asset is its people, and the Secretariat continues to attract staff with a range of expertise in research, review, technology, and law. This breadth has resulted in a diversity of reviews and a professionalized investigative model for addressing complaints.

NSIRA has actively developed a unique culture and is innovative in how it manages its review process. Review teams are comprised of individuals with diverse skill sets that reflect the need for legal and technical expertise. Teams are responsible for executing reviews under the direction of NSIRA members, with the guidance and support of Secretariat management. The result is detailed, fearless reviews.

Similarly, NSIRA’s model for investigations of complaints is now designed for NSIRA members to be expertly supported by legal, registry, and research staff. This enhances members’ effectiveness in their adjudicative role conducting investigations.

NSIRA’s mission is to serve as the trusted eyes and ears of Canadians through independent, expert review and investigation of the Government of Canada’s national security and intelligence activities. To successfully implement its mission, NSIRA must select the right reviews and have access to the required information.

The NSIRA Act requires NSIRA to conduct certain annual reviews; it also gives the agency discretion to choose topics to review. This discretion is fundamental as NSIRA must be able to “follow the thread” to ensure that activities deserving scrutiny are independently reviewed. Specifically, NSIRA has developed a review planning and consideration matrix, consisting of formal criteria that help identify review topics in accordance with NSIRA’s core mandate and mission. The prioritization of reviews is informed by additional strategic factors, including assessments of the nature of the activity and the compliance risk its poses, the novelty of the activity and any technology it employs, as well as resourcing, ongoing reviews, and public interest.

Access to information is the lifeblood of review, and NSIRA continues to insist upon its access rights. Effective review requires timely and complete responses to NSIRA’s requests for information, open and candid briefings, and mutual respect. Despite the agency’s unfettered access under the NSIRA Act, navigating access issues has not been without its struggles. There has been a learning curve, for both reviewed entities and NSIRA, and increasing review literacy in the departments and agencies under NSIRA’s review mandate is an ongoing priority.

NSIRA’s impact on the national security and intelligence community extends beyond that of the reviewed departments. Recently, the Federal Court released a decision on a CSIS warrant matter that used an NSIRA report to inform its background and analysis. The Court considered the issues identified by NSIRA to be important in relation to the sharing of information collected under certain warrants.

Additionally, Ministers accountable for the security and intelligence community’s activities have recognized the value of independent review and have referred matters to NSIRA. The first of such reviews stemmed from a Federal Court judgment. As a result, the Ministers of Public Safety and Justice referred the matter to NSIRA. NSIRA’s report made findings and recommendations on Justice’s provision of legal advice, CSIS and Justice’s management of the warrant acquisition process, and broader cultural and governance issues.

Since 2019, NSIRA has completed 39 reviews (13 statutory and 26 discretionary). Of these reviews, 21 involved more than one department. NSIRA has also issued 17 different compliance reports to responsible Ministers, as required under section 35 of the NSIRA Act, whenever the agency finds that an activity may not be in compliance with the law. Compliance issues range from a department missing a deadline prescribed in legislation to a potential Charter violation. NSIRA’s reports have included more than 200 recommendations, ranging from specific process changes to wide-ranging structural reform. NSIRA has also received more than 200 complaints, highlighting the importance of accessibility to an independent investigation process to address complaints concerning the activities of CSIS, CSE, and the RCMP.

As NSIRA looks to its future, it will also turn attention inward to ensure NSIRA’s structure and governance is fit for purpose. The upcoming legislative review of the NSIRA Act provides the opportunity to make any required improvements.

NSIRA is immensely proud of its contributions to the scrutiny and transparency of Canada’s security and intelligence activities during its first five years. It has played a pivotal role in ensuring there is independent accountability for the organizations involved in Canada’s security and intelligence activities. As NSIRA looks ahead, it does so with enthusiasm and a renewed mission. NSIRA has recently codified its approach by formalizing its vision, mission, and values statements, and while the formal statements may be new, the underlying elements have provided the agency’s foundation from its beginning.

Under NSIRA’s predecessors, international partnerships were primarily established through the Five Eyes Intelligence Oversight and Review Council (FIORC), which continues to be a foundational alliance for NSIRA. In addition to reinforcing and building upon the relationships it inherited, NSIRA has cultivated new partnerships with foreign counterparts and actively participated in international forums. In 2023 alone, NSIRA engaged with the following organizations and attended the following events:

Connecting with international counterparts and participating in multilateral discussions has enabled NSIRA to tap into a network of partners. Relevant information is shared regarding best practices, methodologies, recent developments, and common issues. Information sharing and cooperation in the traditionally esoteric and insulated field of national security oversight has broadened NSIRA’s outlook and informed its expectations with respect to the departments and agencies that it oversees.

NSIRA has found that many of the challenges it faces have been experienced, and in some cases overcome, by international partners. These include challenges that are operational in nature, such as tactics for acquiring and verifying information, and those that relate to NSIRA’s Secretariat, such as the recruitment, training, and retention of staff. Leveraging the lessons learned by our international counterparts has accelerated NSIRA’s own development and contributed to the agency’s growing reputation as an exemplar in the realm of national security and intelligence oversight.

While certainly a voracious consumer of best practices, NSIRA is an equally active contributor. The agency has reciprocally shared its own unique approaches, processes, and methods with the broader oversight community, which in some instances has led partner organizations to follow NSIRA’s lead and adopt its practices. Even where NSIRA has not been confronted with a specific issue firsthand, its perspective has been sought and acted upon by partners that recognize NSIRA’s wealth of experience and renown for innovation.

Continuous and repeated engagements with international partners have allowed for working- level relationships to take root, flourish, and bear fruit in the form of both regularly scheduled touch points and casual, ad hoc, file-specific exchanges. Lowering the institutional barriers has promoted the exchange of expertise, had a more direct impact on the substantive work of each institution, and produced more tangible outcomes, as described in the examples below.

Through an extended assignment to NSIRA, a communications expert from IPCO UK conducted a wholistic assessment of the agency’s current communications posture and played a critical role in crafting an inaugural communications strategy. The implementation of this strategy has helped NSIRA reach and build connections with domestic stakeholders. NSIRA’s members and Secretariat staff are deeply grateful for the expert’s contributions during their time with the agency.

TET Denmark and EOS Norway were influential in the development and use of a new IT system review inspection, first used as part of NSIRA’s Review of the Lifecycle of CSIS’ Warranted Information. They also contributed to functional and performance benchmarking used by NSIRA in its methodologies, common practices, and assessment criteria.

NSIRA has consulted the American Inspector General to improve the responsiveness of reviewed departments and agencies to NSIRA’s recommendations. NSIRA has begun adopting best practices for ensuring there is follow-up on recommendations it has provided.

At an event hosted by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) as part of Canada’s work in cooperation with the UNCTED, NSIRA gave a presentation to the UNCTED delegation to explain the role that independent review plays in assessing the legality of Canadian activities in the counter-terrorism realm. This showcased to international assessors how the Canadian model has built robust independent mechanisms for review of counter-terrorism operations that reaches both law enforcement and the intelligence service.

NSIRA’s review planning and consideration matrix was shared with New Zealand’s IGIS, TET Denmark, and several other international partners. Following their visit to NSIRA, TET Denmark has updated its IT standards to include quality assurance steps and added additional factors to its risk assessment framework.

Just as security and intelligence agencies regularly cooperate and share information with international partners, so too must the bodies that oversee them. Collaboration among NSIRA and its foreign counterparts has produced, and continues to yield, mutual benefits for all parties involved. As a result, NSIRA has become a more capable organization with greater visibility in the transnational security and intelligence community, ensuring effective and exhaustive accountability of Canada’s national security apparatus.

Domestically, within Canada’s review and oversight community, NSIRA brings a distinct and valued perspective, filling a previously unoccupied space in this important network. As such, the agency complements the activities of its peers. In 2023, NSIRA met with numerous Agents of Parliament, including the Auditor General of Canada, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner, and the Privacy Commissioner. The multi-decade institutional experience and maturity of these agents and their respective offices has proven to be invaluably instructive for NSIRA, and the exchange of best practices has been extremely helpful, particularly in the development of the Secretariat’s communications capacity.

As provided for in the NSIRA Act, NSIRA engages with other oversight bodies to deconflict on issues of mutual interest. For example, in 2023, both NSIRA and the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) launched reviews on the issue of political foreign interference. While maintaining its independence, NSIRA coordinated with NSICOP to avoid any unnecessary duplication of work in relation to each organization’s review.

In addition to its annual reviews, NSIRA continued to execute discretionary reviews that it deemed relevant and appropriate to the authorities of its mandate. Of note was NSIRA’s review on the Dissemination of Intelligence on People’s Republic of China Political Foreign Interference, 2018–2023. NSIRA evaluated the flow of intelligence within government from the collectors to consumers, including senior public servants and elected officials. This involved scrutinizing internal processes regarding how collected information was shared and escalated to relevant decision-makers. NSIRA determined that it was in the public interest to report on this matter and produced its first special report under section 40 of the NSIRA Act. This report was tabled in both houses of Parliament in May 2024.

Table 1 captures all review work that was underway in 2023. This includes annually mandated reviews, discretionary reviews, and annual reviews of CSE and CSIS activities. High-level summaries of their content and outcomes are provided in subsequent sections for those reviews completed by the end of the calendar year; the full findings and recommendations can be found in Annex B. NSIRA makes the reviews available once they have been redacted for public release.

| Review | Department(s) | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Report to the Minister of National Defence on CSE activities for 2022 | CSE | Completed |

| Annual Report to the Minister of Public Safety on CSIS activities for 2022 | CSIS | Completed |

| Review of Government of Canada Institutions’ Disclosures of Information Under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act in 2022 | PS, CSE, CSIS, GAC, RCMP, IRCC | Completed |

| Review of CSE’s Network-based Solutions and Related Cybersecurity & Information Assurance Activities | CSE and SSC | Completed |

| Review of CSIS Dataset Regime | CSIS | Completed |

| Review of the Department of National Defence/Canadian Armed Forces’ Human Source Handling Program | DND/CAF | Completed |

| Review of Operational Collaboration Between the CSE and CSIS | CSE and CSIS | Completed |

| Review of the CBSA’s Confidential Human Source Program | CBSA | Completed |

| Review of Departmental Implementation of the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act for 2022 | CBSA, CRA, CSE, CSIS, DFO, DND/CAF, FINTRAC, GAC, IRCC, PS, RCMP, TC | Completed |

| CSE’s Use of the Polygraph for Security Screening | CSE and TBS | Completed |

| Review of the Dissemination of Intelligence on People’s Republic of China Political Foreign Interference, 2018–2023 | CSIS, RCMP, GAC, CSE, PS, PCO | Completed |

| Review of Public Safety Canada and CSIS’s Accountability Mechanisms | CSIS, GAC, PS, DOJ | Completed |

| Review of the Lifecycle of CSIS’ Warranted Information | CSIS | Completed |

| Review of the RCMP’s Human Source Program | RCMP | Completed |

| Review of Government of Canada Institutions’ Disclosures of Information Under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act in 2023 | PS, CSE, CSIS, GAC, RCMP, CBSA, IRCC | Ongoing |

| Review of CSE’s Vulnerabilities Equities Process | CSE, CSIS, RCMP | Ongoing |

| Review of CRA’s Review and Analysis Division (RAD) | CRA | Ongoing |

NSIRA has a mandate to review any Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) activity. The NSIRA Act requires the agency to submit an annual report on CSIS activities each year to the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness. These reports are classified and include information related to CSIS’s compliance with the law and applicable ministerial directions, and the reasonableness and necessity of CSIS exercising its powers.

In 2023, NSIRA completed one dedicated review of CSIS and its annual review of CSIS activities, both summarized below. Furthermore, CSIS is involved in other NSIRA multi-departmental reviews, such as the agency’s review of the operational collaboration between CSE and CSIS, and the legally mandated annual reviews of the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act (SCIDA) and the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act, the results of which are described in section 4.5, Multi-departmental reviews.

In July 2019, the dataset regime came into force as part of the National Security Act 2017 (NSA 2017), creating sections 11.01–11.25 of the CSIS Act.The regime enables CSIS to collect and retain datasets containing personal information that are not directly and immediately related to threats, but likely to assist in national security investigations.

NSIRA examined the implementation of the regime, including aspects of governance, information management, retention practices, and training. The agency found compliance issues that permeated all aspects of the regime under review. Of concern, NSIRA found that CSIS’s current application of the dataset regime is inconsistent with the statutory framework. NSIRA also found multiple compliance issues with how CSIS has implemented the regime, including the retention of Canadian and foreign information without the requisite legally mandated authorizations and approvals.

The review concluded that CSIS has failed to adequately operationalize its dataset regime. CSIS did not seek to clarify legal ambiguities of the application of the regime before the Federal Court, despite having had the opportunity to do so. CSIS adopted multiple positions on its application and now risks limiting what is intended to be a collection and retention regime to a retention mechanism. Internally, CSIS has not provided sufficient resources and training to ensure compliance with the regime. Absent an internal commitment to adequately operationalize, resource, and support the implementation of a new legal regime, any such regime will fail no matter how fit for purpose it is believed to be.

NSIRA completed its annual review of CSIS activities, which covers a range of activities contemplated and undertaken between January 1 and December 31, 2023. The review highlighted compliance-related challenges faced by CSIS, allowed NSIRA to continue monitoring ongoing trends, and identified emerging issues in CSIS’s exercise of its powers. Information obtained throughout the review, including that which CSIS is required to provide to NSIRA under the CSIS Act, was used in NSIRA’s Annual Report to the Minister of Public Safety on CSIS activities, as well as to inform ongoing NSIRA reviews and internal review planning for upcoming reviews.

To achieve greater public accountability, NSIRA has requested that CSIS publish statistics and data about public interest and compliance-related aspects of its activities. NSIRA is of the opinion that the following statistics will provide the public with information related to the scope and breadth of CSIS operations, as well as display the evolution of activities from year to year.

Section 21 of the CSIS Act authorizes CSIS to apply to a judge for a warrant if it believes, on reasonable grounds, that more intrusive powers are required to investigate a particular threat to the security of Canada. Warrants may be used by CSIS, for example, to intercept communications, enter a location, or obtain information, records, or documents. Each individual warrant application could include multiple individuals or request the use of multiple intrusive powers.

| Applications | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022* | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total section 21 applications | 24 | 24 | 15 | 31 | 28 | 30 |

| Total approved warrants | 24 | 23 | 15 | 31 | 28 | 30 |

| New warrants | 10 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 9 |

| Replacements | 11 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 10 |

| Supplemental | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 11 |

| Total denied warrants | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| *The applications submitted by CSIS to the Federal Court in 2022 resulted in the approval and issuance of 194 judicial authorities, including 164 warrants and 28 assistance orders issued pursuant to sections 12, 16, and 21 of the CSIS Act, as well as two judicial authorizations issued pursuant to section 11.13 of the Act. Each application is subject to a thorough production and vetting process that includes review by an independent Department of Justice counsel and challenge by a committee composed of executives of CSIS, PS, CSE, and the RCMP (as applicable) before seeking ministerial approval. A number of warrants issued during this period reflected the development of innovative new authorities and collection techniques, which required close collaboration between collectors, technology operators, policy analysts, and legal counsel. | ||||||

CSIS is authorized to seek a judicial warrant for a threat reduction measure (TRM) if it believes that certain intrusive measures, outlined in section 21 (1.1) of the CSIS Act, are required to reduce a threat. The CSIS Act is clear that when a proposed TRM would limit a right or freedom protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms or would otherwise be contrary to Canadian law, a judicial warrant authorizing the measure is required. To date, CSIS has sought no judicial authorizations to undertake warranted TRMs. TRMs approved in one year may be executed in future years. Operational reasons may also prevent an approved TRM from being executed.

| Threat reduction measures | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approved | 10 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 24 | 11 | 23 | 16 | 14 |

| Executed | 10 | 8 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 8 | 17 | 12 | 19 |

| Warranted | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CSIS is mandated to investigate threats to the security of Canada, including espionage; foreign- influenced activities; political, religious, or ideologically motivated violence; and subversion. Section 12 of the CSIS Act sets out criteria for permitting the Service to investigate an individual, group, or entity for matters related to these threats. Subjects of a CSIS investigation, whether they be individuals or groups, are called “targets.”

| Targets | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of targets | 430 | 467 | 360 | 352 | 340 | 323 |

Data analytics is an investigative tool for CSIS, through which it seeks to make connections and identify trends that may not be visible using traditional methods of investigation. NSA 2017 gave CSIS new powers, including a legal framework for the Service to collect, retain, and use datasets. The framework authorizes CSIS to collect datasets (divided into publicly available, Canadian, and foreign datasets) that may have the ability to assist it in the performance of its duties and functions. It also establishes safeguards for the protection of Canadian rights and freedoms, including privacy rights. These protections include enhanced requirements for ministerial accountability. Depending on the type of dataset, CSIS must meet different requirements before it is able to use a dataset.

The CSIS Act also requires that NSIRA be kept apprised of certain dataset-related activities. Reports prepared following the handling of datasets are to be provided to NSIRA under certain conditions and within reasonable timeframes. While CSIS is not required to advise NSIRA of judicial authorizations or ministerial approvals for the collection of Canadian and foreign datasets, CSIS has been proactively keeping NSIRA apprised of these activities.

| Type of dataset | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publicly available datasets | |||||

| Evaluated | 9 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Retained | 9 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Canadian datasets | |||||

| Evaluated | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Retained (approved by the Federal Court) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Denied by the Federal Court | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Foreign datasets | |||||

| Evaluated | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Retained (approved by the Minister of Public Safety and Intelligence Commissioner) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Denied by the Minister | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Denied by the Intelligence Commissioner | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CSIS’s Justification Framework establishes a limited justification for its employees, and persons acting at their direction, to carry out activities that would otherwise constitute offences under Canadian law. CSIS’s framework is modelled on those already in place for Canadian law enforcement. It provides needed clarity to CSIS, and to Canadians, about what CSIS may lawfully do in the course of its activities. The framework recognizes that it is in the public interest to ensure that CSIS employees can effectively carry out intelligence collection duties and functions, including by engaging in otherwise unlawful acts or omissions, in the public interest and in accordance with the rule of law. The types of otherwise unlawful acts and omissions that are authorized by the Justification Framework are determined by the Minister of Public Safety and approved by the Intelligence Commissioner. There remain limitations on what activities can be undertaken, and nothing in the framework permits the commission of an act or omission that would infringe on a right or freedom guaranteed by the Charter.

According to section 20.1 of the CSIS Act, employees must be designated by the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness to be covered under the Justification Framework while committing or directing an otherwise unlawful act or omission. Designated employees are CSIS employees who require the Justification Framework as part of their duties and functions. Designated employees are justified in committing an act or omission themselves (commissions by employees) and they may direct another person to commit an act or omission (directions to commit) as a part of their duties and functions.

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authorizations | 49 | 147 | 178 | 172 | 172 |

| Commissions by employees | 1 | 39 | 51 | 61 | 47 |

| Directions to commit | 15 | 84 | 116 | 131 | 116 |

| Emergency designations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CSIS’s operational compliance program unit leads and manages overall compliance within the Service. The objective of this unit is to promote a culture of compliance within CSIS by leading an approach for reporting and assessing potential non-compliance incidents that provides timely advice and guidance related to internal policies and procedures for employees. This program is the centre for processing all instances of potential non-compliance related to operational activities.

NSIRA will continue to monitor closely the instances of non-compliance that relate to Canadian law and the Charter, and work with CSIS to improve transparency around these activities.

| Incidents | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processed compliance incidents | 53 | 99 | 85 | 59 | 79 |

| Administrative | 53 | 64 | 42 | 48 | |

| Operational | 40a | 19b | 21 | 17 | 31 |

| Canadian law | N/A | N/A | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Charter | N/A | N/A | 6 | 5 | 15 |

| Warrant conditions | N/A | N/A | 6 | 3 | 11 |

| CSIS governance | N/A | N/A | 8 | 15 | 27 |

| a For 2021, each operational non-compliance incident was reported based on the highest non-compliance (i.e., if the incident were non-compliant with the Charter and CSIS governance, it would be counted only under the Charter category). For 2022 and 2023, each incident is counted in all of the areas in which it was non-compliant. As such, the sum of operational non-compliance in the various categories exceeds the total number of such incidents. | |||||

| b The total number of incidents of non-compliance were not further broken down in 2019 and 2020. This number represents the number of incidents of non-compliance with requirements such as the CSIS Act, the Charter, warrant terms and conditions, or CSIS internal policies or procedures. | |||||

NSIRA has the mandate to review any activity conducted by the Communications Security Establishment (CSE). NSIRA must submit an annual report to the Minister of National Defence on CSE activities, including information related to CSE’s compliance with the law and applicable ministerial directions, and NSIRA’s assessment of the reasonableness and necessity of CSE exercising its powers.

In 2023, NSIRA completed two dedicated reviews of CSE and commenced an annual review of CSE activities, summarized below. Furthermore, CSE is included in other NSIRA multi-departmental reviews, such as the review of the operational collaboration between CSE and CSIS and the legally mandated annual reviews of the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act (SCIDA) and the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (see section 4.5).

NSIRA’s review of CSE’s use of the polygraph for security screening found that the policies and procedures in place at CSE inadequately addressed privacy issues. In particular, CSE’s use of personal information collected during polygraph exams for staffing purposes may have exceeded the consent provided and may not have complied with section 7 of the Privacy Act.

NSIRA also found issues with the way in which CSE operated its polygraph program, including unnecessarily repetitive and aggressive questioning by examiners, insufficient quality control of exams, and retention issues related to audiovisual recordings. Additionally, the way in which CSE used the results of polygraph exams to inform security screening decision-making could cause uncertainty over the opportunity to challenge denials of security clearances pursuant to the NSIRA Act. CSE generally over-relied on the results of polygraph exams for deciding security screening cases. When taken as a whole, CSE’s use of the polygraph for security screening raised serious concerns related to the Charter.

NSIRA also explored the role of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) in establishing the Standard on Security Screening (the Standard), which governs the use of the polygraph for security screening by the Government of Canada. NSIRA found that TBS did not adequately consider the privacy or Charter implications of the use of the polygraph. TBS also did not implement sufficient safeguards in the Standard to address these implications.

As a result, NSIRA recommended that CSE and TBS both urgently address the fundamental issues related to the legality, reasonableness, and necessity of the use of the polygraph for security screening. If these issues cannot be addressed, NSIRA recommended that TBS remove the polygraph from the Standard and CSE should cease using it for security screening.

Since the CSE Act came into force in 2019, CSE’s cybersecurity and information assurance (CSIA) activities have grown in extent and importance. CSE acquires and analyzes vast amounts of information to identify and prevent cybersecurity threats, a necessary activity that nonetheless engages important privacy interests, a balance NSIRA sought to understand.

This was NSIRA’s first review of CSE’s CSIA activities, along with its first review of Shared Services Canada (SSC). The two departments work together on CSIA activities, as SSC is the system owner for most Government of Canada networks.

NSIRA found that CSE operates a comprehensive and integrated ecosystem of cybersecurity systems, tools, and capabilities to protect against cyber threats, with a design that incorporates measures meant to protect the privacy of Canadians and persons in Canada.

NSIRA made findings and recommendations in two areas of concern:

NSIRA built foundational knowledge about CSE’s CSIA activities through this review, which will inform NSIRA’s future activities.

NSIRA conducted the second annual review of CSE activities. The 2023 review aimed to identify compliance-related challenges, general trends, and emerging issues based on information CSE is required by law to provide to NSIRA, as well as supplementary information. Primarily resulting in NSIRA’s Annual Report to the Minister of National Defence on CSE activities, the review also identified areas for future reviews of CSE activities and bolstered NSIRA’s knowledge of CSE activities.

To achieve greater accountability and transparency, NSIRA has requested statistics and data from CSE about public interest and compliance-related aspects of its activities. NSIRA is of the opinion that these statistics will provide the public with important information related to the scope and breadth of CSE operations, as well as display the evolution of activities from year to year.

Ministerial authorizations are issued to CSE by the Minister of National Defence. The authorizations support specific foreign intelligence, cybersecurity activities, defensive cyber operations, or active cyber operations conducted by CSE pursuant to those aspects of its mandate. Authorizations are issued when these activities could otherwise contravene an Act of Parliament or interfere with a reasonable expectation of privacy of a Canadian or a person in Canada.

| Type of ministerial authorization | Enabling section of the CSE Act | Issued in 2019 | Issued in 2020 | Issued in 2021 | Issued in 2022 | Issued in 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign intelligence | 26(1) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Cybersecurity (federal and non-federal) | 27(1) and 27(2) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Defensive cyber operations | 29(1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Active cyber operations | 30(1) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

Ministerial orders are issued by the Minister for the purpose of (1) designating any electronic information, any information infrastructures, or any class of electronic information or information infrastructures as electronic information or information infrastructures of importance to the Government of Canada (section 21[1] of the CSE Act); or (2) designating recipients of information related to Canadians or persons in Canada – that is, Canadian-identifying information (sections 45 and 44[1] of the CSE Act).

| Name of ministerial order | Enabling section of the CSE Act |

|---|---|

| Designating Recipients of Canadian Identifying Information Used, Analyzed or Retained Under a Foreign Intelligence Authorization | 43 |

| Designating Recipients of Information Relating to a Canadian or Person in Canada Acquired, Used or Analyzed Under the Cybersecurity and Information Assurance Aspects of the CSE Mandate | 44 |

| Designating Electronic Information and Information Infrastructures of Importance to the Government of Canada | 21 |

| Designating Electronic Information and Information Infrastructures of Ukraine as of Importance to the Government of Canada | 21 |

| Designating Electronic Information and Information Infrastructures of Latvia as of Importance to the Government of Canada | 21 |

Under section 16 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to acquire information from or through the global information infrastructure. The CSE Act defines the global information infrastructure as including electromagnetic emissions; any equipment producing such emissions; communications systems; information technology systems and networks; and any data or technical information carried on, contained in, or relating to those emissions, that equipment, those systems, or those networks. CSE uses, analyzes, and disseminates the information for providing foreign intelligence in accordance with the Government of Canada’s intelligence priorities.

| CSE foreign intelligence reporting | 2020 (#) | 2021 (#) | 2022 (#) | 2023 (#) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reports released | Not available | 3,050 | 3,185 | 3,184 |

| Departments and agencies | >25 | 28 | 26 | 28 |

| Specific clients within departments and agencies | >2,100 | 1,627 | 1,761 | 2,049 |

Information relating to a Canadian or a person in Canada (IRTC) is information about Canadians or persons in Canada that may be incidentally collected by CSE while conducting foreign intelligence or cybersecurity activities under the authority of a ministerial authorization. Incidental collection refers to information acquired that CSE was not deliberately seeking and where the activity that enabled its acquisition was not directed at a Canadian or a person in Canada. According to CSE policy, IRTC is defined as any information recognized as having reference to a Canadian or person in Canada, regardless of whether that information could be used to identify that Canadian or person in Canada.

CSE was asked to release statistics or data about the regularity with which IRTC is included in CSE’s end-product reporting. CSE responded that this information “remains classified and cannot be published.”

CSE is prohibited from directing its activities at Canadians or persons in Canada. However, its collection methodologies sometimes result in incidentally acquiring such information. When such incidentally collected information is used in CSE’s foreign intelligence reporting, any part that potentially identifies a Canadian or a person in Canada is suppressed to protect the privacy of the individual(s) in question. CSE may release unsuppressed Canadian-identifying information (CII) to designated recipients when the recipients have the legal authority and operational justification to receive it, and when it is essential to international affairs, defence, or security (including cyber security).

| Type of request | 2021 (#) | 2022 (#) | 2023 (#) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government of Canada requests | 741 | 657 | 1,087 |

| Five Eyes requests | 90 | 62 | 142 |

| Non-Five Eyes requests | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 831 | 719 | 1,229 |

In 2023, of the 1,229 requests received, CSE reported having denied 281 requests. By the end of the calendar year, 40 were still being processed.

CSE was asked to release the number of instances where CII is suppressed in CSE foreign intelligence or cyber security reporting. It indicated that this information “remains classified and cannot be published.”

A privacy incident occurs when the privacy of a Canadian or a person in Canada is put at risk in a manner that runs counter to, or is not provided for, in CSE’s policies. CSE tracks such incidents through its Privacy Incidents File, and for privacy incidents that are attributable to a second-party partner or a domestic partner, through its Second-Party Privacy Incidents File.

| Type of incident | 2021 (#) | 2022 (#) | 2023 (#) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy incidents | 96 | 114 | 107 |

| Second-party privacy incidents | 33 | 23 | 37 |

| Non-privacy compliance incidents | Not available | Not available | 28 |

| Type of incident | 2023 (#) |

|---|---|

| Privacy incidents | 70 |

| Second-party privacy incidents | 37 |

| Non-privacy compliance incidents | 16 |

| Type of incident | 2023 (#) |

|---|---|

| Privacy incidents | 37 |

| Non-privacy compliance incidents | 12 |

Under section 17 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to provide advice, guidance, and services to help protect electronic information and information infrastructures of federal institutions, as well as those of non-federal entities that are designated by the Minister of National Defence as being of importance to the Government of Canada.

The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) is Canada’s unified authority on cybersecurity. The Cyber Centre, which is a part of CSE, provides expert guidance, services, and education while working in collaboration with stakeholders in the private and public sectors. The Cyber Centre handles incidents in government and designated institutions that include:

| Type of cyber incident | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Federal institutions | 1,070 | 977 |

| Critical infrastructure | 1,575 | 1,756 |

| International | Not available | 82 |

| Total | 2,645 | 2,815 |

Under section 18 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to conduct defensive cyber operations (DCO) to help protect electronic information and information infrastructures of federal institutions, as well as those of non-federal entities that are designated by the Minister as being of importance to the Government of Canada, from hostile cyber attacks.

Under section 19 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to conduct active cyber operations (ACO) against foreign individuals, states, organizations, or terrorist groups as they relate to international affairs, defence, or security.

CSE was asked to release the number of DCOs and ACOs approved, and the number carried out in 2023. CSE responded that this information “remains classified and cannot be published.”

As part of the assistance aspect of CSE’s mandate, CSE receives requests for assistance from Canadian law enforcement and security agencies, as well as from the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (DND/CAF).

| Action | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approved | 23 | 32 | 59 | 48 |

| Not approved | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Under review | Not available | Not available | 0 | 2 |

| Cancelled | Not available | Not available | 1 | 0 |

| Denied | Not available | Not available | 2 | 1 |

| Total received | 24 | 35 | 62 | 53 |

| Note: For 2020 and 2021, CSE was able to provide only the number of requests received and actioned. CSE advised, however, that it has since improved its internal tracking system for requests for assistance. | ||||

In addition to the CSIS and CSE reviews above, NSIRA completed the following reviews of departments and agencies in 2023:

This review examined the legal and policy frameworks governing CBSA’s Confidential Human Source (CHS) program. The review had three areas of focus: the management and assessment of risk; CBSA’s discharge of its duty of care to its sources; and the sufficiency of ministerial direction and accountability in relation to the program. Together, these areas support CBSA’s ability to conduct its human source-handling activities lawfully, ethically, and with appropriate accountability.

The review reflects that, as an investigative tool used in support of CBSA’s mandate, the CHS Program rests on an adequate legal framework. However, the review found a number of gaps in the framework governing the program and was especially attentive to how CBSA manages the particular risks associated with the use of human sources without status in Canada. The review contains a number of findings that relate to CBSA’s risk management practices.

In two instances, NSRIA’s review concluded that CBSA’s activities may not be in compliance with the law. In the first, the review concluded through a detailed case study that CBSA may have twice breached the law of informer privilege by improperly disclosing information that might identify the human source. In this and another instance, NSIRA found that CBSA failed to inform the Minister of Public Safety of a human source activity that may have impacted the safety of an individual, as required by the Ministerial Direction on Surveillance and Confidential Human Sources. This constitutes non-compliance with subsection 12(2) of the CBSA Act.

NSIRA made six recommendations in this review. Collectively, they are meant to enhance the governance of the human source program to ensure CBSA is attentive to the welfare of its human sources across the full spectrum of activities. They also reflect NSIRA’s ongoing attention to the principle of ministerial accountability. Overall, NSIRA’s findings and recommendations reflect the level of maturity of CBSA’s program; although it has been operating for almost 40 years, the introduction of the policy suite specific to human sources is a relatively recent innovation. The review also reflects CBSA’s recent efforts to improve its program.

This review examined whether DND/CAF conducts its human source-handling activities lawfully, ethically, and with appropriate accountability.

NSIRA found that DND/CAF’s policy framework allows human source-handling activities that may not be in compliance with the law. These risks arise particularly in relation to sources associated with terrorist groups. NSIRA recommended that Parliament enact a justification framework that would authorize DND/CAF and its sources to commit otherwise unlawful acts outside Canada, where reasonable for the collection of defence intelligence.

NSIRA found that DND/CAF’s risk assessment frameworks do not provide commanders with the accurate, consistent, and objective information they need to evaluate the risks of engaging with particular sources. NSIRA recommended that these frameworks be revised to ensure that all applicable risk factors are considered.

NSIRA found gaps in DND/CAF’s discharge of its duty of care to sources. Safeguarding processes were not always appropriately engaged; the complaints process was underdeveloped; and the risk posed to agents was, at times, insufficiently assessed. Measures to address these issues should be clearly operationalized in governance documents.

NSIRA found that the Minister of National Defence is not sufficiently informed on human source-handling operations to fulfill their ministerial accountabilities. The Minister should be aware of the legal, policy, and governance issues that may affect human source-handling operations.

NSIRA also found that further ministerial direction is required to support the governance of DND/CAF’s human source handling program. NSIRA recommended that the Minister issue ministerial direction to DND/CAF that will guide the lawful and ethical conduct of source-handling operations.

CSE and CSIS are two core pillars of Canadian intelligence collection, which means that effective collaboration between the departments is critical to national security. However, a tension exists between CSIS’s mandate, which authorizes collection and sharing of information about Canadians, and CSE’s core prohibition against directing its activities at Canadians. This is the first review that was able to access information from both departments and consider that tension.

NSIRA examined a sample of CSE and CSIS collaborative operational activities and information sharing, as well as collaboration between CSIS and CSE further to CSIS’s threat reduction measure (TRM) mandate. This satisfied NSIRA’s annual requirement under section 8(2) of the NSIRA Act to review an aspect of CSIS’s TRMs.

With respect to operational collaboration, including under CSIS’s TRM mandate, NSIRA found a lack of information sharing and proactive planning, as well as a failure on CSE’s part to properly account for and mitigate the risk of targeting Canadians when working with CSIS. NSIRA recommended some procedural changes to improve information flow, consultation, transparency, and accountability.

Concerning information sharing, NSIRA found that existing processes between the departments lacked guidance and accountability, and created risks of CSE targeting Canadians that were actualized in some instances. NSIRA recommended both departments establish policies, procedures, and analyst training. Additionally, NSIRA recommended that CSIS cease making requests to CSE pertaining to Canadians and consider the Canadian information it shares with CSE. NSIRA also recommended that CSE reconsider how it collects, retains, and reports Canadian information in certain scenarios and only use foreign lead information from CSIS reporting.

In this review, NSIRA found two cases of non-compliance with the law. Both involved CSE directing its activities at Canadians under its foreign intelligence mandate.

This review provided an overview of the use of the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act (SCIDA) in 2022. In doing so, it documented the volume and nature of information disclosures made under the SCIDA, assesses compliance with the Act, and highlights patterns in its use across Government of Canada institutions and over time.

In 2022, four disclosing institutions made a total of 173 disclosures to five recipient institutions. NSIRA found that institutions complied with the SCIDA’s requirements for disclosure and record keeping in relation to the majority of these disclosures. Observed instances of non-compliance that were related to subsection 9(3), regarding the timeliness of records copied to NSIRA; subsection 5.1(1), regarding the timeliness of destruction or return of personal information; and subsection 5(2), regarding the provision of a statement on accuracy and reliability. These instances did not point to any systemic failures in Government of Canada institutions’ implementation of the Act.

NSIRA also made findings in relation to practices that, although compliant with the SCIDA, left room for improvement. NSIRA’s corresponding recommendations were designed to increase standardization across the Government of Canada in a manner that is consistent with the institutions’ demonstrated best practices and the Act’s guiding principles.

Overall, NSIRA observed improvements in reviewee performance compared to findings from prior years’ reports and over the course of the review. These improvements include corrective actions taken by reviewees in response to NSIRA’s requests for information in support of this review.

This review assessed departments’ compliance with the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACA) and their implementation of the ACA’s associated directions during the 2022 calendar year. Within this context, the review pursued a thematic focus on departments’ conduct of risk assessments, including the ways in which their methodologies may lead to a systematic under-assessment of the level of risk involved in an information-sharing transaction.

NSIRA’s findings and recommendations in this report reflect both developments and stagnations in departments’ implementation of the directions over time. NSIRA observed efforts to collaborate interdepartmentally and standardize certain practices across the Government of Canada. While these efforts reflect an improvement over past approaches, they fall short of the consistent framework for foreign information sharing government-wide envisioned by the Act. Additionally, NSIRA observed a number of practices that may lead departments to systematically under-assess the risks involved in contemplated information exchanges. Such under-assessments may in turn lead to information being exchanged, in contravention of the directions’ prohibitions.

NSIRA made five recommendations in this review. Collectively, they would ensure that all departments’ ACA frameworks reflect a degree of standardization commensurate with the spirit of the Act and its associated directions; and that these frameworks are designed to support compliance with the directions.

NSIRA is mandated to investigate national security-related public complaints. NSIRA complaint investigations are conducted with consistency, fairness, and timeliness. The agency’s public complaint mandate plays a critical role in ensuring that Canada’s national security and intelligence organizations are accountable to the Canadian public.

In 2022, NSIRA had committed to establishing service standards for the investigation of complaints, with the goal of completing 90 percent of investigations within its new service standards. These service standards were implemented and have been in effect since April 1, 2023, and set internal time limits for certain investigative steps for each type of complaint, under normal circumstances. NSIRA is pleased to report that for the period of April 1 to December 31, 2023, 100 percent of the service standards have been met across all investigation files subject to these service standards.

While remaining mindful of the interests of the complainant and the security imperatives of the organization, NSIRA established an independent verification process with CSE for new complaints filed under section 17 of the NSIRA Act. More specifically, after receiving a complaint, NSIRA must evaluate whether it is within NSIRA’s jurisdiction to investigate, based on conditions stated in the NSIRA Act. For complaints against CSE, just as with complaints against CSIS and the RCMP, NSIRA must be satisfied that the complaint against the respondent organization refers to an activity carried out by the organization and is not trivial, frivolous, or vexatious. This new independent verification process assists NSIRA in ascertaining its jurisdiction to investigate complaints filed against CSE.

NSIRA has developed a new internal tracking tool to ensure effective case management of complaint files.