Protected: Review of Government of Canada Institutions’ Disclosures of Information Under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act in 2023: Backgrounder

- Date Modified:

Date of Publishing:

This quarterly report has been prepared by management as required by section 65.1 of the Financial Administration Act and in the form and manner prescribed by the Directive on Accounting Standards, GC 4400 Departmental Quarterly Financial Report. This quarterly financial report should be read in conjunction with the 2023–24 Main Estimates.

This quarterly report has not been subject to an external audit or review.

The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) is an independent external review body that reports to Parliament. Established in July 2019, NSIRA is responsible for conducting reviews of the Government of Canada’s national security and intelligence activities to ensure that they are lawful, reasonable and necessary. NSIRA also hears public complaints regarding key national security agencies and their activities.

A summary description NSIRA’s program activities can be found in Part II of the Main Estimates. Information on NSIRA’s mandate can be found on its website.

This quarterly report has been prepared by management using an expenditure basis of accounting. The accompanying Statement of Authorities includes the agency’s spending authorities granted by Parliament and those used by the agency, consistent with the 2023–24 Main Estimates. This quarterly report has been prepared using a special-purpose financial reporting framework (cash basis) designed to meet financial information needs with respect to the use of spending authorities.

The authority of Parliament is required before money can be spent by the government. Approvals are given in the form of annually approved limits through appropriation acts or through legislation in the form of statutory spending authorities for specific purposes.

This section highlights the significant items that contributed to the net increase or decrease in authorities available for the year and actual expenditures for the quarter ended September 30, 2023.

NSIRA Secretariat spent approximately 52% of its authorities by the end of the third quarter, compared with 39% in the same quarter of 2022–23 (see graph 1).

| 2023-24 | 2022-23 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Authorities | $24.4 | $29.8 |

| Q2 Expenditures | $4.8 | $4.7 |

| Year-to-Date Expenditures | $12.8 | $11.6 |

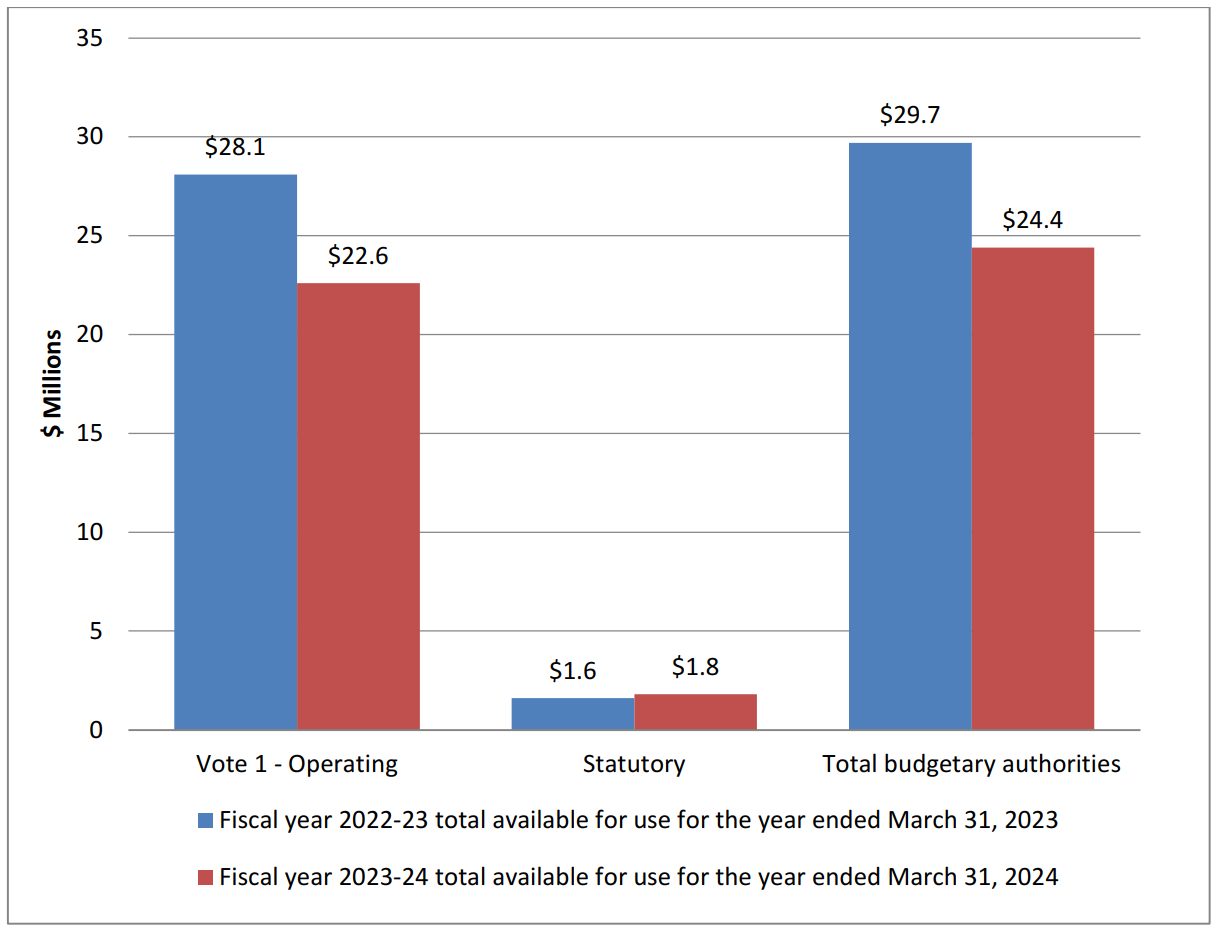

As at December 31, 2023, Parliament had approved $24.4 million in total authorities for use by NSIRA Secretariat for 2023–24 compared with $29.8 million as of December 31, 2022, for a net decrease of $5.3 million or 18% (see graph 2).

| Fiscal year 2022-23 total available for use for the year ended March 31, 2023 | Fiscal year 2023-24 total available for use for the year ended March 31, 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

| Vote 1 – Operating | 28.1 | 22.6 |

| Statutory | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Total budgetary authorities | 29.7 | 24.4 |

The decrease of $5.3 million in authorities is mostly explained by a gradual reduction in NSIRA Secretariat’s ongoing operating funding due to an ongoing construction project nearing completion.

The third quarter expenditures totalled $4.8 million for an increase of $0.1 million when compared with $4.7 million spent during the same period in 2022–2023. Table 1 presents budgetary expenditures by standard object.

| Variances in expenditures by standard object(in thousands of dollars) | Fiscal year 2023–24: expended during the quarter ended December 31, 2023 | Fiscal year 2022–23: expended during the quarter ended December 31, 2022 | Variance $ | Variance % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel | 2,866 | 2,503 | 363 | 15% |

| Transportation and communications | 110 | 82 | 28 | 34% |

| Information | 1 | 4 | (3) | (75%) |

| Professional and special services | 486 | 1,271 | (785) | (62%) |

| Rentals | 78 | 83 | (5) | (6%) |

| Repair and maintenance | 1,161 | 685 | 476 | 69% |

| Utilities, materials and supplies | (1) | 21 | (22) | (105%) |

| Acquisition of machinery and equipment | 83 | 2 | 81 | 4050% |

| Other subsidies and payment | (33) | 17 | (50) | (294%) |

| Total gross budgetary expenditures | 4,751 | 4,668 | 83 | 2% |

*Details may not sum to totals due to rounding*

The decrease of $785,000 is due to the timing of invoicing for our Internal Support Services agreement.

The increase of $476,000 is due to the timing of invoicing for an ongoing capital project.

The decrease of $22,000 is due to a temporarily unreconciled acquisition card suspense account.

The increase of $81,000 is due to the purchase of software licenses and the corresponding support and maintenance.

The decrease of $50,000 is explained by a prior year refund that was deposited to NSIRA’s account in error.

The year-to-date expenditures totalled $12.8 million for an increase of $1.2 million (11%) when compared with $11.6 million spent during the same period in 2022–23. Table 2 presents budgetary expenditures by standard object.

| Variances in expenditures by standard object(in thousands of dollars) | Fiscal year 2023–24: year-to-date expenditures as of December 31, 2023 | Fiscal year 2022–23: year-to-date expenditures as of December 31, 2022 | Variance $ | Variance % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personnel | 8,766 | 7,751 | 1,015 | 13% |

| Transportation and communications | 302 | 196 | 106 | 54% |

| Information | 5 | 9 | (4) | (44%) |

| Professional and special services | 2,155 | 2,695 | (540) | (20%) |

| Rentals | 151 | 132 | 19 | 14% |

| Repair and maintenance | 1,188 | 749 | 439 | (59%) |

| Utilities, materials and supplies | 56 | 49 | 7 | 14% |

| Acquisition of machinery and equipment | 135 | 15 | 120 | 800% |

| Other subsidies and payment | 89 | 18 | 71 | 394% |

| Total gross budgetary expenditures | 12,847 | 11,614 | 1,233 | 11% |

*Details may not sum to totals due to rounding*

The increase of $1,015,000 relates to an increase in average salary, an increase in full time equivalent (FTE) positions, and back-pay from the new collective agreement for the EC and AS occupational groups.

The increase in $106,000 is due to the timing of the invoicing for our internet connections.

The decrease of $540,000 is mainly explained by the conclusion of guard services contracts associated to a capital construction project and the timing of invoicing for internal support services.

The increase of $439,000 is due to the timing of invoicing for an ongoing capital project.

The increase of $120,000 is mainly explained by the one-time purchase of a specialized laptop and licenses.

The increase of $71,000 is due to an increase in salary overpayments.

The NSIRA Secretariat has made progress on accessing the information required to conduct reviews; however, there continues to be risks associated with reviewees’ ability to respond to, and prioritize, information requests, hindering NSIRA’s ability to deliver its review plan in a timely way. The NSIRA Secretariat will continue to mitigate this risk by providing clear communication related to information requests, tracking their timely completion within communicated timelines, and escalating issues when appropriate.

There is a risk that the funding received to offset pay increases anticipated over the coming year will be insufficient to cover the costs of such increases and the year-over-year cost of services provided by other government departments/agencies is increasing significantly.

Mitigation measures for the risks outlined above have been identified and are factored into NSIRA Secretariat’s approach and timelines for the execution of its mandated activities

There have been no changes to the NSIRA Secretariat Program.

John Davies

Executive Director

Martyn Turcotte

Director General, Corporate Services, Chief Financial Officer

(in thousands of dollars)

| Fiscal year 2023–24 | Fiscal year 2022–23 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total available for use for the year ending March 31, 2024 (note 1) | Used during the quarter ended December 31, 2023 | Year to date used at quarter-end | Total available for use for the year ending March 31, 2023 (note 1) | Used during the quarter ended December 31, 2022 | Year to date used at quarter-end | |

| Vote 1 – Net operating expenditures | 22,633 | 4,313 | 11,531 | 28.063 | 4,236 | 10,318 |

| Budgetary statutory authorities | ||||||

| Contributions to employee benefit plans | 1,755 | 438 | 1,316 | 1,728 | 432 | 1,296 |

| Total budgetary authorities (note 2) | 24,388 | 4,751 | 12,847 | 29,791 | 4,668 | 11,614 |

Note 1: Includes only authorities available for use and granted by Parliament as at quarter-end.

Note 2: Details may not sum to totals due to rounding.

(in thousands of dollars)

| Fiscal year 2023–24 | Fiscal year 2022–23 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned expenditures for the year ending March 31, 2024 (note 1) | Expended during the quarter ended December 31, 2023 | Year to date used at quarter-end | Planned expenditures for the year ending March 31, 2023 | Expended during the quarter ended December 31, 2022 | Year to date used at quarter-end | |

| Expenditures | ||||||

| Personnel | 13,372 | 2,866 | 8,766 | 13,389 | 2,503 | 7,751 |

| Transportation and communications | 650 | 110 | 302 | 597 | 82 | 196 |

| Information | 371 | 1 | 5 | 372 | 4 | 9 |

| Professional and special services | 4,906 | 486 | 2,155 | 4,902 | 1,271 | 2,695 |

| Rentals | 271 | 78 | 151 | 271 | 83 | 132 |

| Repair and maintenance | 4,580 | 1,161 | 1,188 | 9,722 | 685 | 749 |

| Utilities, materials and supplies | 73 | (1) | 56 | 173 | 21 | 49 |

| Acquisition of machinery and equipment | 132 | 83 | 135 | 232 | 2 | 15 |

| Other subsidies and payments | 33 | (33) | 89 | 133 | 17 | 18 |

| Total gross budgetary expenditures (note 2) |

24,388 | 4,751 | 12,847 | 29,791 | 4,668 | 11,614 |

Note 1: Includes only authorities available for use and granted by Parliament as at quarter-end.

Note 2: Details may not sum to totals due to rounding.

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

24-08

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

24-07

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

24-05

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

24-01

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

24-06

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

23-14

Last Updated:

Status:

In Progress

Review Number:

23-13