- Revisions

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Background

- Findings, Analysis, and Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Annex A. Findings and Recommendations

- Part 1: CSIS’s collection and dissemination of intelligence on PRC foreign interference in the 2019 and 2021 federal elections

- Part 2: The SITE Task Force and the CEIPP Panel

- Part 3: The flow of intelligence on PRC foreign interference

- Part 1: CSIS’s collection and dissemination of intelligence on PRC foreign interference in the 2019 and 2021 federal elections

- Part 2: The SITE Task Force and the CEIPP Panel

- Part 3: The flow of intelligence on PRC foreign interference

Date of Publishing:

Revisions

Pursuant to section 40 of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act (NSIRA Act), NSIRA may submit a special report to the appropriate Minister on any matter related to NSIRA’s mandate. The Minister must then table the special report in Parliament within 15 sitting days.

Prior to the submission of such a report, subsection 52(1)(b) of the NSIRA Act requires NSIRA to consult with the deputy heads concerned to ensure that the special report does not contain information the disclosure of which would be injurious to national security, national defence or international relations or is information that is protected by solicitor-client privilege, the professional secrecy of advocates and notaries or litigation privilege.

This document is NSIRA’s section 40 special report. It is a revised version of the classified report provided to the Prime Minister on March 5, 2024. Revisions were made to remove injurious information. Where information could simply be removed without affecting the readability of the document, NSIRA noted the removal with three asterisks (***). Where more context was required, NSIRA revised the document to summarize the information that was removed. Those sections are marked with three asterisks at the beginning and the end of the summary, and the summary is enclosed by square brackets (see example below).

EXAMPLE: [**Revised sections are marked with three asterisks at the beginning and the end of the sentence, and the summary is enclosed by square brackets.**]

List of Acronyms

| Abbreviation | Expansion |

|---|---|

| CEIPP | Critical Election Incident Public Protocol |

| CTSN | Canadian Top Secret Network |

| CSE | Communications Security Establishment |

| CSIS | Canadian Security Intelligence Service |

| DND | Department of National Defence |

| DM | Deputy Minister |

| FI | Foreign Interference |

| GAC | Global Affairs Canada |

| HUMINT | Human Intelligence |

| IAS | Intelligence Assessment Secretariat |

| ISR | Independent Special Rapporteur |

| MP | Member of Parliament |

| NHQ | National Headquarters |

| NSIA | National Security and Intelligence Advisor |

| NSICOP | National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians |

| NSIRA | National Security and Intelligence Review Agency |

| PCO | Privy Council Office |

| PRC | People’s Republic of China |

| PMO | Prime Minister’s Office |

| PSB | Protective Security Briefing |

| PS | Public Safety Canada |

| RCMP | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| RRM | Rapid Response Mechanism |

| SIGINT | Signals Intelligence |

| SITE TF | Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections Task Force |

| TRM | Threat Reduction Measure |

| UFWD | United Front Work Department |

| Abréviation | Développement |

|---|---|

| AC | Administration centrale |

| AMC | Affaires mondiales Canada |

| BCP | Bureau du Conseil privé |

| CPM | Cabinet du premier ministre |

| CPSNR | Comité des parlementaires sur la sécurité nationale et le renseignement |

| CSNR | Conseiller à la sécurité nationale et au renseignement |

| CST | Centre de la sécurité des télécommunications |

| DER | Direction de l’évaluation du renseignement |

| DTFU | Département du travail du Front uni |

| GRC | Gendarmerie royale du Canada |

| GT MSRE | Groupe de travail sur les menaces en matière de sécurité et de renseignements visant les élections |

| HUMINT | Renseignement humain (Human Intelligence) |

| IE | Ingérence étrangère |

| MDN | Ministère de la Défense nationale |

| MRM | Mesure de réduction de la menace |

| MRR | Mécanisme de réponse rapide |

| OSSNR | Office de surveillance des activités en matière de sécurité nationale et de renseignement |

| PPIEM | Protocole public en cas d’incident électoral majeur |

| RCTS | Réseau canadien Très secret |

| RPC | République populaire de Chine |

| RSI | Rapporteur spécial indépendant |

| SCRS | Service canadien du renseignement de sécurité |

| SIGINT | Renseignement électromagnétique (Signals Intelligence) |

| SISP | Séance d’information sur la sécurité préventive |

| SM | Sous ministre |

| SP | Sécurité publique Canada |

Executive Summary

The security and intelligence community is of the consensus view that political foreign interference is a significant threat to Canada, and that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is a major perpetrator of this threat at all levels of government. Nonetheless, the present review of how intelligence related to PRC political foreign interference was disseminated from 2018 to 2023 (a period covering the last two federal elections) indicates that there were significant disagreements between constituent components of that community, both within and across organizations, as to whether, when, and how to share what they knew.

Underlying these disagreements and misalignments was a basic challenge for the security and intelligence community: how to address the so-called “grey zone” whereby political foreign interference may stand in close proximity to typical political or diplomatic activity. NSIRA saw evidence of this challenge across the activities under review, including in decisions about whether to disseminate information and how to characterize what was shared. The risk of characterizing legitimate political or diplomatic behaviour as a threat led some members of the intelligence community to not identify certain activities as threat activities.

Intelligence is by its nature provisory. It does not constitute proof that the described activities took place, or took place in the manner suggested by the source(s) of the information. At the same time, the fact that it is not proof does not mean it should be withheld – by this standard, very little (if any) intelligence would ever be shared. What is required – between collection and dissemination – is an evaluation of the intelligence and a decision as to whether it should, or should not, be communicated in some way.

With respect to disseminating intelligence about foreign interference in elections, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) confronted a basic dilemma. On one hand, information about foreign interference in elections was a priority for the government, and CSIS had geared its collection apparatus toward investigating political foreign interference. On the other, CSIS was sensitive to the possibility that the collection and dissemination of intelligence about elections could itself be construed as a form of election interference. A basic tension held: any action – including the dissemination of intelligence – taken by CSIS prior to or during an election must not, and must not be seen to, influence that election.

This dynamic was known within CSIS, but is not formally addressed in policy or guidelines. It was not always clear, particularly to those collecting intelligence, what the general rationale and/or policy guiding the dissemination of intelligence on political foreign interference was, let alone how that rationale/policy applied to specific decisions. Overall, the perception arose within CSIS that rules and decisions were being made, and frequently changed, absent a coherent strategy or guiding principles.

NSIRA recommends that CSIS develop a comprehensive policy and strategy specifically pertaining to all aspects of how CSIS engages – investigates, reports about, and takes action against – threats of political foreign interference. This would bring coherence across the organization. It would also signal to Government of Canada stakeholders that CSIS has carefully considered all aspects of political foreign interference, including its unique sensitivities, and is reporting and advising on those threats using rigorous standards and thresholds.

CSIS is a member of the Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) Task Force, along with the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), and Global Affairs Canada (GAC). One of the Task Force’s primary functions is to provide coordinated intelligence reporting to a panel of senior public servants, the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol (CEIPP) Panel, during writ periods. These two bodies were established to receive, analyze, and respond to intelligence coming from the intelligence community with respect to foreign interference in federal elections.

The orientations of the SITE Task Force and CEIPP Panel were geared toward addressing broad, systematic, and largely online interference (such as that witnessed in the 2016 US presidential election). As such, they could not adequately address so-called traditional, human-based, riding-by-riding interference. NSIRA recommends several adjustments to the SITE Task Force and CEIPP Panel, meant to ensure that the full range of threats associated with foreign interference is adequately addressed by these two entities moving forward.

Outside the election context, the intelligence community collects intelligence on PRC political foreign interference on an ongoing basis. This intelligence is shared both horizontally within the community and vertically to senior decision makers, including elected officials.

During the review period, CSIS lacked the ability to definitively track who had received and read its intelligence. This was partly a consequence of the internal tracking systems of the various recipient departments, which may not have comprehensively captured this data. In the end, however, it is incumbent on CSIS, as the originator of sensitive information, to control and document access.

The consequences of not knowing who has received what manifested in the controversy regarding intelligence related to the PRC targeting of a sitting Member of Parliament.

The media and public conversation regarding this intelligence focused on two CSIS products, one from May 2021 and the other from July 2021. In fact, neither product was the mechanism through which the Minister and Deputy Minister of Public Safety were initially meant to be informed of the PRC’s threat activities against the Member of Parliament and his family. Rather, [**prior to May 2021**] there [**was CSIS intelligence**] related to the PRC’s targeting of the Member of Parliament. CSIS sent [**this intelligence**] to named-recipient lists which included the Deputy Minister and Minister of Public Safety.

Public Safety confirmed that at least one [**redacted**] was provided to the Minister [**prior to May**] 2021, likely as part of a weekly reading package. However, the department was unable to account for [**redacted**]. This is an unacceptable state of affairs. NSIRA recommends that, as a basic accountability mechanism, CSIS and Public Safety rigorously track and document who has received and, as appropriate, read intelligence products.

At the same time, tracking who has received what is not a panacea. There must be interest on the part of consumers for the intelligence they receive, and an understanding as to how the intelligence can support the fulfillment of their responsibilities.

In 2021, PCO and CSIS analysts produced reports meant to serve as synthesizing overviews of PRC foreign interference activities, but which the National Security and Intelligence Advisor to the Prime Minister (NSIA) saw as recounting standard diplomatic activity. This disagreement played a role in those intelligence products not reaching the political executive, including the Prime Minister.

The gap between CSIS’s point of view and that of the NSIA is significant, because the question is so fundamental. CSIS collected, analyzed, and reported intelligence about activities that it considered to be significant threats to national security; one of the primary consumers of that reporting (and the de facto conduit of intelligence to the Prime Minister) disagreed with that assessment. Commitments to address political foreign interference are straightforward in theory, but will inevitably suffer in practice if rudimentary disagreements as to the nature of the threat persist in the community.

NSIRA recommends that regular consumers of intelligence work to enhance intelligence literacy within their departments and that, further, the security and intelligence community develop a common, working understanding of what constitutes political foreign interference. While the NSIA plays a coordinating role within the security and intelligence community, the bounds of this role are not formally delineated. As such, the extent of their influence in decisions regarding the distribution of CSIS intelligence products is unclear. NSIRA therefore recommends that the role of the NSIA, including with respect to decisions regarding the dissemination of intelligence, be described in a legal instrument.

Introduction

Authority

This review was conducted under the authority of paragraphs 8(1)(a) and 8(1)(b) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act (NSIRA Act).

Scope of the Review

The scope of the review included all intelligence on People’s Republic of China (PRC) foreign interference in federal democratic institutions and processes from 2018 to 2023. The specific focus was on the flow of this intelligence within government. That is, from the collectors of intelligence to consumers of intelligence (“clients”), including senior public servants and elected officials.

The review included the following departments and agencies:

- The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS)

- The Communications Security Establishment (CSE)

- The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

- Global Affairs Canada (GAC)

- Public Safety Canada (Public Safety)

- The Privy Council Office (PCO)

These are the core members of the security and intelligence community with mandates relevant to foreign interference in Canadian democratic institutions and processes. The review also received information from Elections Canada regarding its relationship with, and the information it received from, the departments and agencies noted above.

Methodology

NSIRA gathered information through a variety of means. This included:

- Document Review (approximately 17,000 documents);

- Nine (9) Briefings;

- Fourteen (14) Interviews;

- Twenty-one (21) Requests for Information;

- These included requests for documents as well as requests for written responses to questions.

- Direct Access to CSIS’s operational database and corporate repository.

- Direct access to CSE’s foreign intelligence reporting database.

The NSIRA Act grants NSIRA rights of timely access to any information in the possession or under the control of a reviewed entity (reviewee), with the exception of Cabinet confidences, and to receive from them any documents and explanations NSIRA deems necessary.

Initially, NSIRA did not request the release of Cabinet confidences, as the scope of the review did not include policy responses to foreign interference from government, focussing instead on the flow of information within government. However, in his initial public report, the Independent Special Rapporteur on Foreign Interference (ISR), the Right Honourable David Johnston, recommended that NSIRA be given access to any Cabinet confidences that were provided to him for his review. In light of this recommendation, on June 7, 2023, NSIRA wrote to the Prime Minister to request that all Cabinet confidences related to its review be released to the Review Agency, and not just those reviewed by the ISR.

On June 13, 2023, an Order in Council authorized the release, to NSIRA, of the Cabinet confidences reviewed by the ISR. The scope and focus of NSIRA’s review differs from the ISR’s May 23, 2023 report. The ISR’s report focused specifically on intelligence related to foreign interference in the 43rd and 44th general federal elections and reported on in the media. To safeguard the integrity of its reviews and maintain its independence, NSIRA could not consider a subset of Cabinet confidences (those provided to the ISR) without reviewing all other Cabinet confidences relevant to NSIRA’s particular scope and focus. NSIRA’s broader request to the Prime Minister went unanswered. As a result, NSIRA declined to consider the subset of Cabinet confidences that were provided. Given the scope of the review, NSIRA is nonetheless confident that it received all information necessary to fully support its analysis, findings and recommendations. Pursuant to its obligations under s. 13 of the NSIRA Act, NSIRA cooperated with the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP) to avoid any unnecessary duplication of work in relation to each organization’s review of the topic of foreign interference.

Review Statements

CSIS, CSE, the RCMP, GAC, and Public Safety met NSIRA’s expectations for responsiveness during this review. PCO only partially met NSIRA’s expectations, due to delays in responding to requests for information.

NSIRA was able to verify information for this review in a manner that met expectations.

Background

Beginning in the fall of 2022, a series of reporting by The Globe and Mail and Global News cited classified CSIS documents on PRC foreign interference into Canadian democratic institutions and processes, including the 43rd and 44th federal elections. This reporting raised concerns regarding the government’s response to the threat of foreign interference and, consequently, the integrity of Canada’s democratic institutions and processes.

On March 9, 2023, NSIRA announced that it would initiate the present review of the production and dissemination of intelligence on foreign interference with respect to the 43rd and 44th federal elections. The review’s focus was on the flow of this information within government, in order to address the fundamental question: did the security and intelligence community adequately report information to those responsible for protecting Canada’s democratic processes and institutions from threats of foreign interference? The granularity of this question – which includes comparing collected raw information to the intelligence ultimately disseminated in finished products – lent itself to NSIRA’s unique mandate and access, including direct access to CSIS’s systems and the ability to speak to intelligence officers in the field. Broader policy considerations (for example what policymakers did or did not do with the information they received) were considered out of scope, and should be addressed by other organizations reviewing activities in this area, including NSICOP and the Commission of Inquiry under the direction of the Honourable Marie-Josée Hogue. NSIRA’s question is foundational in that an effective response requires adequate information.

Political Foreign Interference

Foreign interference includes covert, clandestine or deceptive activities undertaken by foreign actors to advance their strategic, geopolitical, economic, and security interests. This can occur in any sphere of society, including the private sector, academia, the media, and the political system. The latter, political foreign interference, is a subset of foreign interference more broadly.

A prominent example of political foreign interference is the spreading and amplifying of disinformation on social media platforms, such as was perpetrated by Russia during the 2016 US presidential election. Also prevalent are “traditional” (human-based) forms of interference which consist of, among other things: cultivating relationships with political officials for the purpose of interference activities; the recruitment and coercion of individuals involved in politics (including political staff); illicit, illegal, or clandestine financial donations to politicians or political parties; and targeting diaspora communities through threats and intimidation.

According to Canada’s security and intelligence community, the largest perpetrator of foreign interference (political or otherwise) in Canada is the PRC. The PRC engages in widespread and systematic interference operations at all levels of government. These activities are generally the purview of the PRC’s United Front Work Department (UFWD), which is dedicated to shaping and influencing perceptions of, and policy toward, the PRC on a global scale, through a variety of overt and covert means. While the UFWD has been in existence for decades, it is widely recognized that its activities have accelerated following the accession of Xi Jinping to permanent leadership of the PRC, coinciding with increasing tensions between the PRC and Western nations, including Canada.

CSIS has reported about foreign interference since its inception in 1984. The CSIS Act defines “threats to the security of Canada” in section 2, including what it calls “foreign influenced activities” which are “activities that are detrimental to the interests of Canada and are clandestine or deceptive or involve a threat to any person.”

CSIS’s reporting on PRC foreign interference has been subject to public controversy in the past. Most notably, in 2010, then-CSIS Director Richard Fadden made public statements regarding PRC political foreign interference in Canada, indicating that CSIS was investigating multiple politicians whom it believed were “under the influence of a foreign government.” These comments generated significant public criticism, including from the House Committee on Public Safety and National Security, which concluded that “the allegations made by the Director of CSIS tarnished the reputation of politicians and of the Chinese-Canadian community.”

Eventually, in [**redacted**], CSIS created dedicated desks to investigate PRC foreign interference; [**One sentence edited and one sentence deleted to remove injurious information. The sentences described the organization of CSIS investigations**]. CSIS noted to NSIRA that the volume of foreign interference activity was significant, [**redacted**].

In the following years, investigations have continued to evolve, even as the sensitivity of investigating and reporting about political foreign interference (as demonstrated by the Fadden controversy) remains acute. This tension – between pushing forward on investigations related to foreign interference and tempering such efforts to account for the sensitivities involved – permeated all of the activities examined below. Intelligence is by its nature provisory. It does not constitute proof that the described activities took place, or took place in the manner suggested by the source(s) of the information. That intelligence was “collected” does not imply, necessarily, that it ought to have been disseminated to government clients. At the same time, the fact that it is not proof does not mean it should be withheld – by this standard, very little (if any) intelligence would ever be shared. What is required – between collection and dissemination – is an evaluation of the intelligence and a decision as to whether it should, or should not, be communicated in some way. This process, and these decisions, are fundamental to the work of the security and intelligence community. They are at the heart of the present review.

Findings, Analysis, and Recommendations

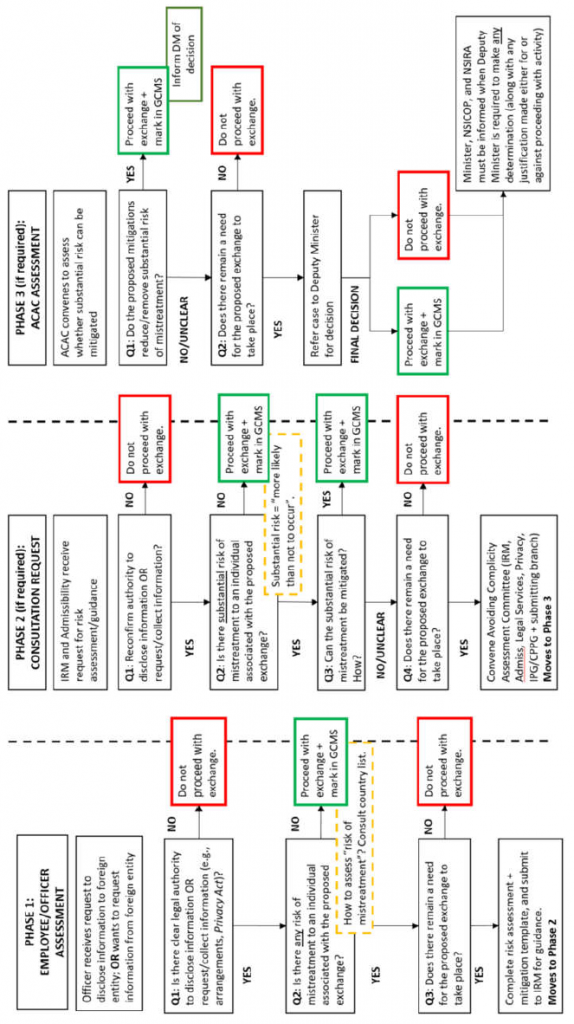

This section presents the review’s findings, supporting analysis, and resulting recommendations. The section is organized into three parts, as follows:

- Part 1 reviews CSIS’s dissemination of intelligence on PRC foreign interference in the 43rd and 44th federal elections. Assessing this flow was the principal aim of the review. NSIRA selected three cases for in-depth review. The details of these cases, along with other information reviewed by NSIRA, inform general findings related to the dissemination of intelligence on PRC political foreign interference, culminating in a broad recommendation to CSIS regarding its governance in this area.

- Part 2 examines the role of the Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) Task Force and Critical Election Incident Public Protocol (CEIPP) Panel. These bodies were established to receive, analyze, and respond to intelligence provided by the intelligence community. The analysis highlights deficiencies and provides recommendations to better position these bodies to address the threat of political foreign interference.

- Part 3 steps away from the election-specific context, to assess the broader flow of intelligence on PRC political foreign interference across the security and intelligence community between 2018 and 2023, including to senior public servants and elected officials. Particular attention is given to CSIS’s methods of dissemination, and the role of the National Security and Intelligence Advisor (NSIA) to the Prime Minister. This analysis includes an overview of the dissemination of intelligence regarding the PRC’s targeting of a Member of Parliament, and an assessment of the dissemination of two in-depth analytical intelligence products on PRC political foreign interference.

Taken collectively, these components offer insight into the overall challenges associated with how intelligence about PRC political foreign interference moved within the Government of Canada during the review period.

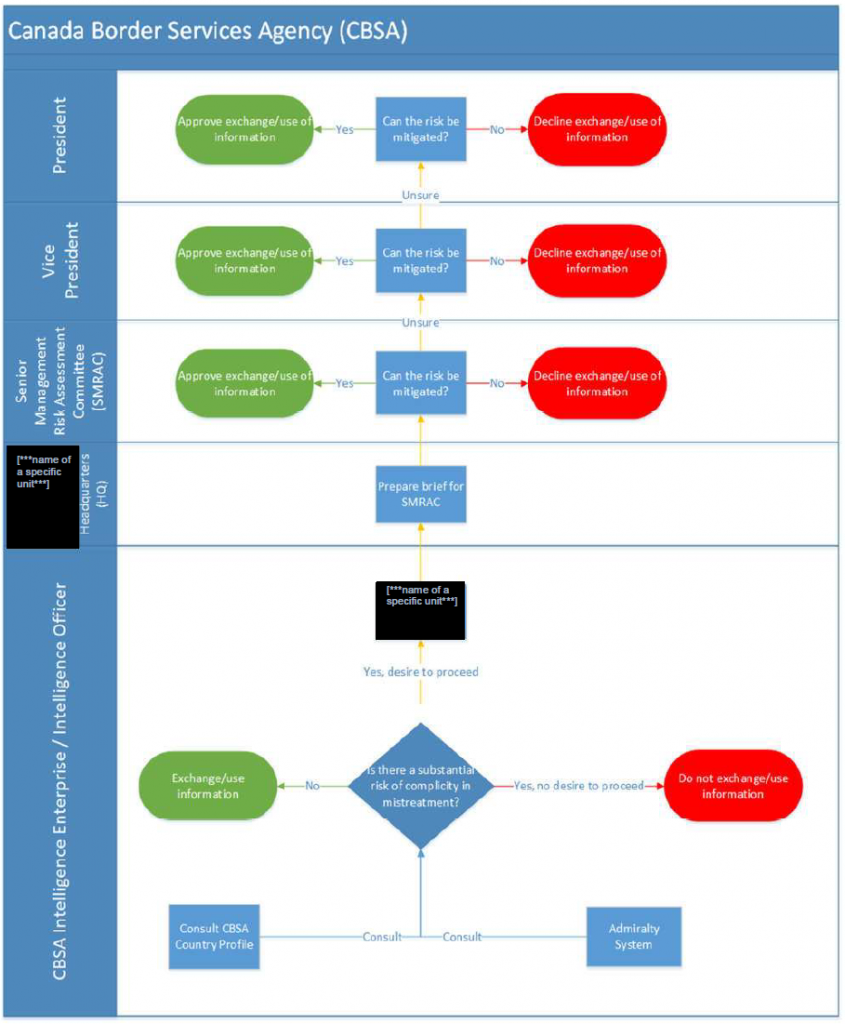

Part 1: CSIS’s collection and dissemination of intelligence on PRC foreign interference in the 2019 and 2021 federal elections

NSIRA reviewed the intelligence produced by CSIS, CSE, GAC, PCO, and the RCMP related to foreign interference in the 43rd and 44th federal elections. In three cases – one from 2019, two from 2021 – NSIRA examined how CSIS disseminated intelligence to relevant entities in the government of Canada, including the SITE Task Force and CEIPP Panel.

Case Study 1 (2019 election)

Case Study 1 involved collected intelligence on PRC foreign interference activities in support of a federal election candidate.

Intelligence associated with this case was widely disseminated, including to the SITE Task Force, the candidate’s party, Elections Canada, the Office of the Commissioner of Canada Elections, senior public servants (including the CEIPP Panel), the Minister of Public Safety, and the Prime Minister. However, in certain instances the dissemination of intelligence lacked timeliness and clarity.

For example, CSIS disseminated and then recalled a key analytical intelligence product on the case prior to the election. On October 1, 2019, CSIS released a six-page National Security Brief on PRC foreign interference activities associated with the case. The brief was disseminated to a list of named recipients, including senior public servants and representatives of the SITE Task Force. Ten days later, on October 10, CSIS recalled the product, and requested that all recipients destroy the copies that had been provided. This decision was taken by the CSIS Director, following a conversation with the NSIA. When asked by NSIRA to explain the rationale behind recalling the product, CSIS indicated that neither the Director nor the Director’s office could remember the specifics of the decision, other than that it was by request of the NSIA.

At the same time, the analysis and associated assessment included in the product were provided (though not necessarily with the same detail) in oral briefings. On September 28, CSIS (in its capacity as a member of the SITE Task Force and facilitated by PCO) briefed Secret-cleared members of the candidate’s party on the intelligence indicating PRC foreign interference. Two days later, on September 30, the CSIS Director briefed this intelligence and CSIS’s assessment to the CEIPP Panel.

The Prime Minister was not directly briefed by CSIS on intelligence regarding PRC foreign interference associated with the case until February of 2021, sixteen months following the election. Nonetheless, the Prime Minister may have indirectly been made aware of the relevant CSIS intelligence. PCO noted that a briefing by PCO to the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) on “issues related to [Case Study 1] likely took place in late September/early October 2019”, but could not provide NSIRA any documentation to this effect. Further, there is evidence to suggest that the Prime Minister was informed of the content of CSIS’s September 28 briefing on September 29.

In December 2019, the PCO Assistant Secretary of Security and Intelligence prepared a memorandum to the NSIA recommending that the NSIA brief the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff on CSIS’s assessment [**redacted**]. The briefing would also have raised the potential vulnerabilities in the candidate nomination process. PCO indicated that there was no record confirming that the memorandum was delivered to the NSIA (though PCO was “confident that [the NSIA] was made aware of the information it contained”) and no record that the PMO was briefed as per the memorandum’s recommendation. The NSIA and the Clerk of the Privy Council, as members of the CEIPP Panel, received the September 30, 2019, briefing. In January 2020, CSIS briefed them again on the same issue. CSIS then briefed the Minister of Public Safety on the case in March 2020.

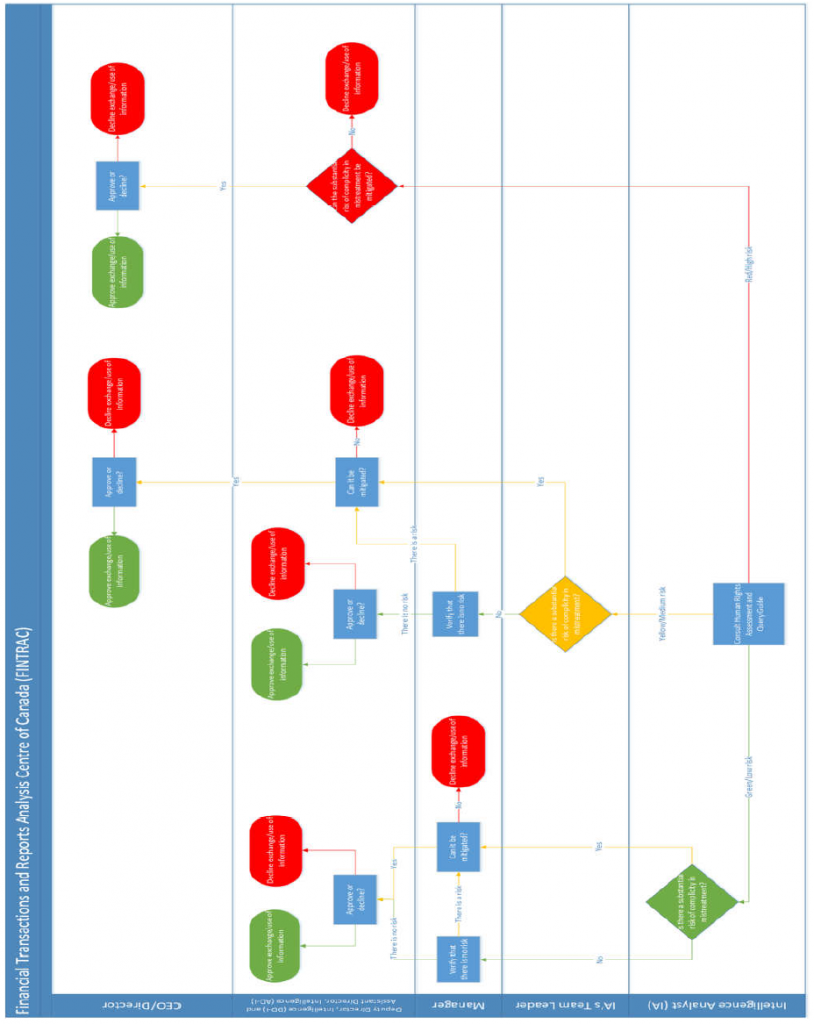

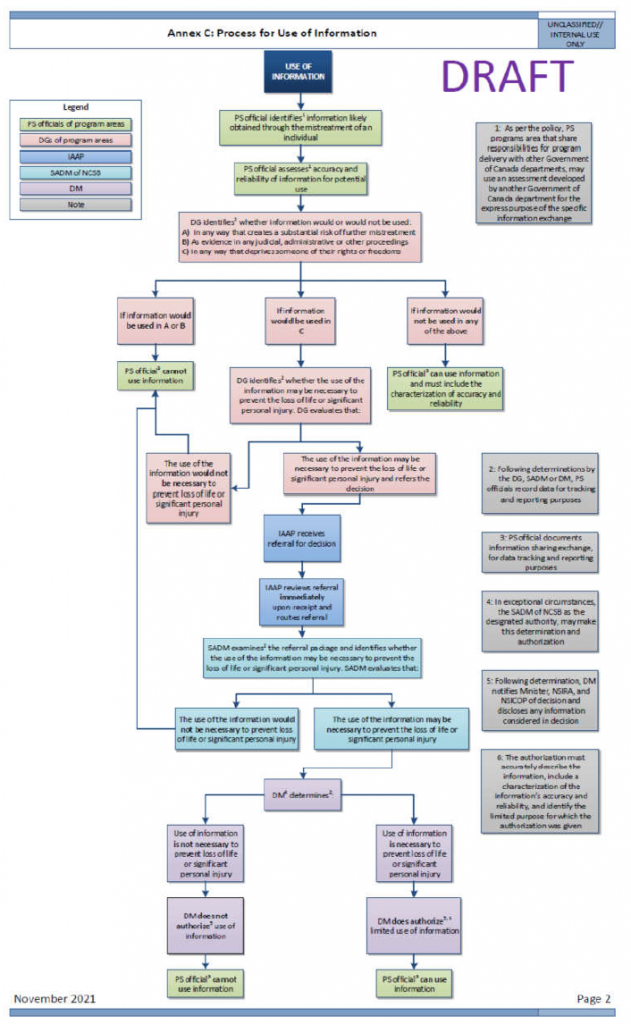

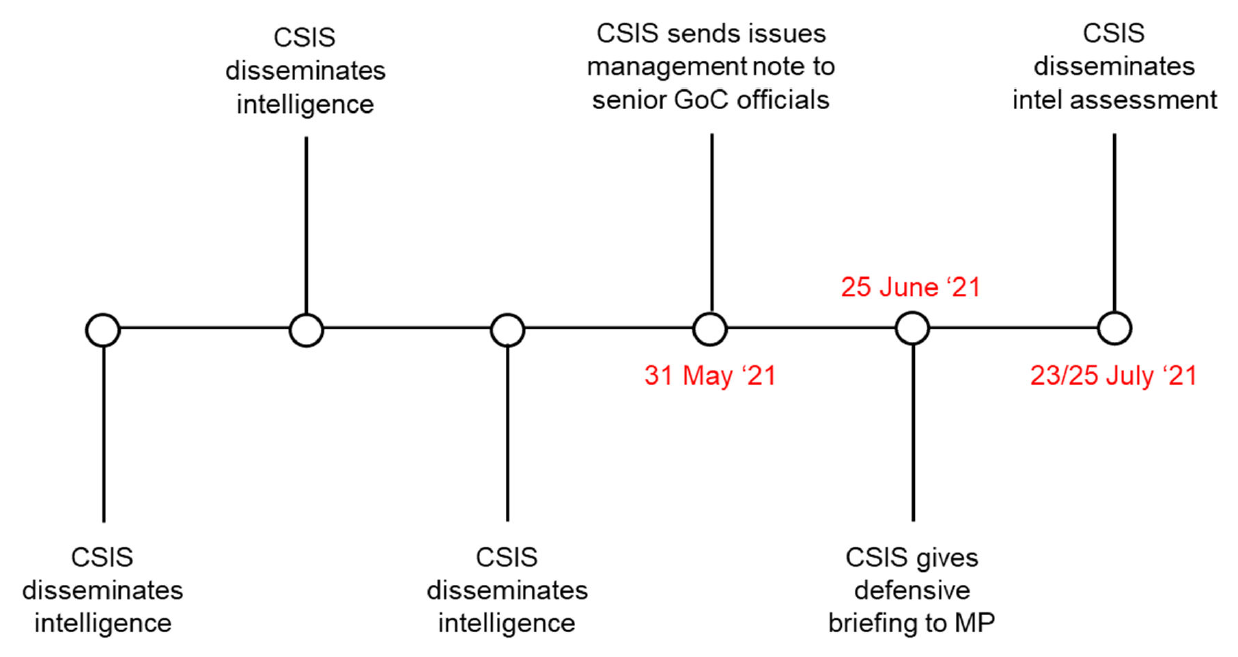

Figure 1. Keydates, dissemination of intelligence on Case Study 1

[**Figure has been edited to remove injurious information**]

Early intelligence reporting on foreign interference activities related to the case did not sufficiently distinguish typical political activity from threat-related foreign interference. While this distinction was largely implicit, absent a clear articulation of why CSIS believed that specific activities constituted foreign interference, consumers – particularly those familiar with the tactics of political campaigns – may not have appreciated the intended import of the intelligence provided.

Case Study 2 (2021 election)

Case Study 2 involved collected intelligence on PRC foreign interference activities [**redacted**].

Intelligence associated with Case Study 2 was disseminated to [**redacted**], the SITE Task Force, the CEIPP Panel and, shortly following the election, the Prime Minister.

While this dissemination was timely, CSIS deviated from its most common dissemination practices by limiting the number of written Intelligence Reports. It is unclear whether there was an explicit, blanket decision to suspend all Intelligence Report production on Case Study 2 during the election period, or whether the lack of Intelligence Reports was the natural consequence of case-by-case situational factors.

CSIS considered several options for addressing/mitigating foreign interference in this case. [**redacted**]. CSIS deliberated as to whether [**redacted**] should occur before or after the election. Ultimately, the risks of [**redacted**] were considered prohibitive. CSIS noted in particular the risk that if its efforts became public, CSIS might be blamed for interfering in the democratic process [**redacted**].

[**Two sentences deleted to remove injurious information. The sentences describe the dissemination of intelligence related to PRC foreign interference activities**].

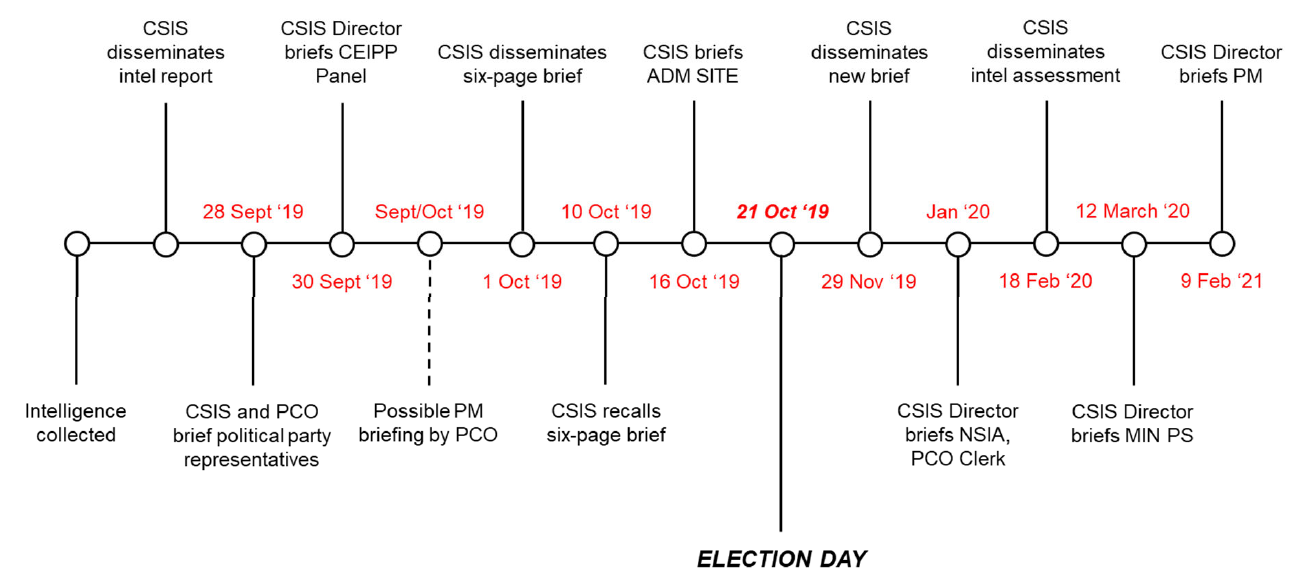

Figure 2. Key dates, dissemination of intelligence on Case Study 2

[**Figure has been edited to remove injurious information**]

As in Case Study 1, there were also issues in terms of consumers understanding the intended significance of the intelligence provided. For example, a member of the CEIPP Panel requested clarification as to how the activities were “deceptive and clandestine” (key components of CSIS’s definition of foreign interference) [**redacted**]. [**redacted**]. CSIS further noted that the PRC [**redacted**], ignoring the general notice from GAC to all foreign diplomatic missions in Canada that direct or indirect [**involvement**] in the election was inappropriate.

The intelligence CSIS collected was provided to relevant entities – in particular the CEIPP Panel [**redacted**] – in advance of the election. Indeed, according to those familiar with the Panel’s work, [**redacted**] was considered a clear “success” in terms of the 2021 election. This perception is generally shared by CSIS, [**redacted**] informing senior public officials [**redacted**].

Nonetheless, CSIS deviated from its most common dissemination process, at least partly as a consequence of the subject matter (political foreign interference). Further, that CSIS could not definitively say whether an explicit decision had been made to eschew written intelligence products is itself indicative of a lack of clarity with respect to how intelligence on political foreign interference ought to be handled, particularly during elections.

Overall, Case Study 2 is most instructive not as an example of the failed or inadequate dissemination of intelligence, but as further illustration of the unique challenges associated with disseminating intelligence on political foreign interference that, when combined with other examples and cases, reveal broader, systemic issues with how CSIS communicates the information it collects about political processes.

Case Study 3 (2021 election)

Case Study 3 involved collected intelligence on PRC foreign interference across several ridings in a specific geographic region, as well as broader campaigns, with a nexus to that region, targeting the election as a whole. There were multiple pieces of intelligence, on different activities, collected at different times, from different sources, subject to different caveats and considerations, disseminated (or not) at different moments, in different formats, to different recipients.

Decisions regarding whether, when, and how to disseminate this intelligence were the subject of disagreement, uncertainty, and lack of communication within CSIS. This disconnect was largely between intelligence officers collecting intelligence in the region, and those responsible for disseminating that intelligence at National Headquarters (NHQ) (NHQ includes both the [**dedicated unit in NHQ combining operational and analytical capabilities (hereafter referred to as “dedicated unit in NHQ”)**] and the CSIS executive). Put simply, intelligence officers did not understand why some of the intelligence they collected was either not disseminated at all or disseminated following what they perceived to be atypical delays. NHQ, by contrast, often had reasons for not disseminating (or delaying) intelligence – typically tied to the unique nature of political foreign interference – that were not communicated or, in the absence of standard criteria or rationale, appeared arbitrary.

Intelligence related to PRC foreign interference in a particular riding is a case in point. [**One sentence deleted to remove injurious information. The sentence discussed the date(s) of collection and the threat activities described by the intelligence**]. The desk collecting and analyzing this intelligence believed it was worthy of being placed into an Intelligence Report for dissemination, particularly because it related directly to the election. In [**Fall 2021**], multiple emails were sent from the region to the [**dedicated unit in NHQ**] requesting an explanation as to why the information had not been disseminated. Eventually, the intelligence was placed into an Intelligence Report (***) and disseminated on [**redacted**] 2021. To the desk, this delay (***) significantly reduced the impact of the information.

Additional intelligence [**redacted**] regarding other examples/instances of PRC foreign interference was never disseminated. In [**redacted**] 2021, a regional analyst drafted an analytical product incorporating this intelligence in order to detail [**redacted**] PRC foreign interference. However, a senior analyst at the [**dedicated unit in NHQ**] found that the draft product insufficiently contextualized [**redacted**] PRC foreign interference. While the regional desk recognized [**redacted**] it nonetheless believed that appropriate caveats (as are often included in CSIS reporting [**redacted**]) could have sufficiently contextualized the information.

[**Dedicated unit in NHQ**], by contrast, believed that [**redacted**] problematized the intelligence, such that reporting it would require “contextualizing [**redacted**]. The concern was that the [**redacted**] information [**redacted**] if disseminated absent this context and characterization. For the region, this perceived reticence to push out collected information suggested that different standards were being applied to intelligence on political foreign interference.

There were also challenges and disagreements with respect to intelligence pertaining to broader interference campaigns. Following the election, a political party sent a letter to PCO detailing what they believed to be foreign interference against their candidates in thirteen federal ridings. At the core of the party’s concerns was an online disinformation campaign directed against them.

The SITE Task Force, specifically CSIS and GAC’s Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) team, devoted significant analysis to this campaign. Ultimately, neither CSIS nor the RRM definitively linked the campaign directly to the PRC. The SITE Task Force’s After Action Report for the 2021 election, finalized in December 2021, concluded that [**one sentence edited to remove injurious information. The sentence summarized the SITE Task Force’s conclusion that it could not definitively link online narratives against the political party to a foreign state actor**]

However, prior to the publication of this report, in [**redacted**] 2021, CSIS collected intelligence [**redacted**] the online disinformation campaign against the political party.

There was disagreement within CSIS as to how to characterize [**redacted**] in the online campaign, and whether or not intelligence about [**redacted**] should or should not be disseminated as intelligence indicating PRC foreign interference. [**Two sentences deleted to remove injurious information. The sentences discussed competing perspectives between the region and a dedicated unit in NHQ regarding how to characterize intelligence regarding potential foreign interference activities**]

The crux of these competing perspectives was differing orientations to, and appreciation for, the sensitivities associated with reporting about political foreign interference, which manifested in different attitudes regarding the threshold for intelligence reporting. [**Two sentences deleted to remove injurious information. The sentences described competing interpretations within CSIS with respect to certain intelligence on possible foreign interference activities, and corresponding differences of opinion regarding dissemination of that intelligence**] This would ensure consumers of the intelligence that CSIS was not simply reporting on the normal political activity [**redacted**] routinely involved in the political process, but rather on activities which posed a threat to Canada’s national security.

A draft Intelligence Report detailing [**redacted**] in foreign interference during the 2021 election was not disseminated. Rather, this intelligence was repurposed into a more general product on [**redacted**] foreign interference activities overall. In July 2022, [**dedicated unit in NHQ**] advised the region that they were delaying publication of the longer intelligence product until they could secure [**redacted**]for the inclusion of [**redacted**] SIGINT as part of the analysis. The region, by contrast, felt that the product as drafted sufficiently established [**redacted**] threat activities, and ought to be disseminated right away. Given that CSIS could itself view the [**redacted**] SIGINT, delaying dissemination to include this information in the product suggests CSIS felt the need to convince consumers of CSIS’s assessment [**redacted**] rather than simply providing that assessment in its capacity as the security intelligence service of Canada. [**Dedicated unit in NHQ**] further noted that the CSIS executive planned to discuss the product with senior officials outside of CSIS (including the NSIA and the Clerk of the Privy Council) prior to finalization.

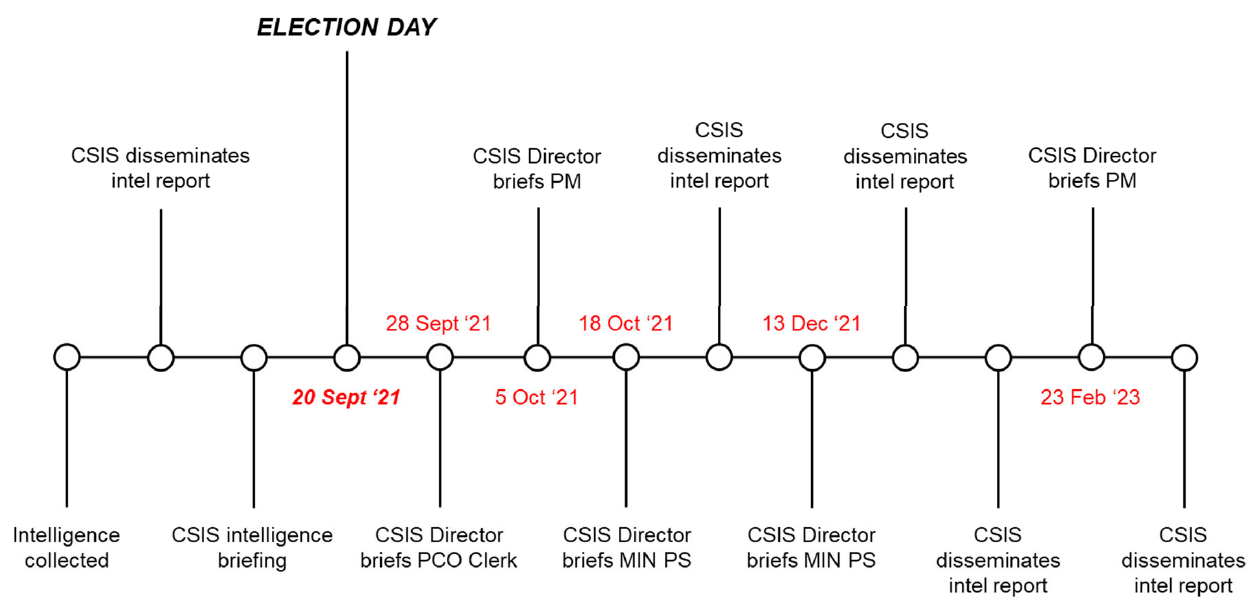

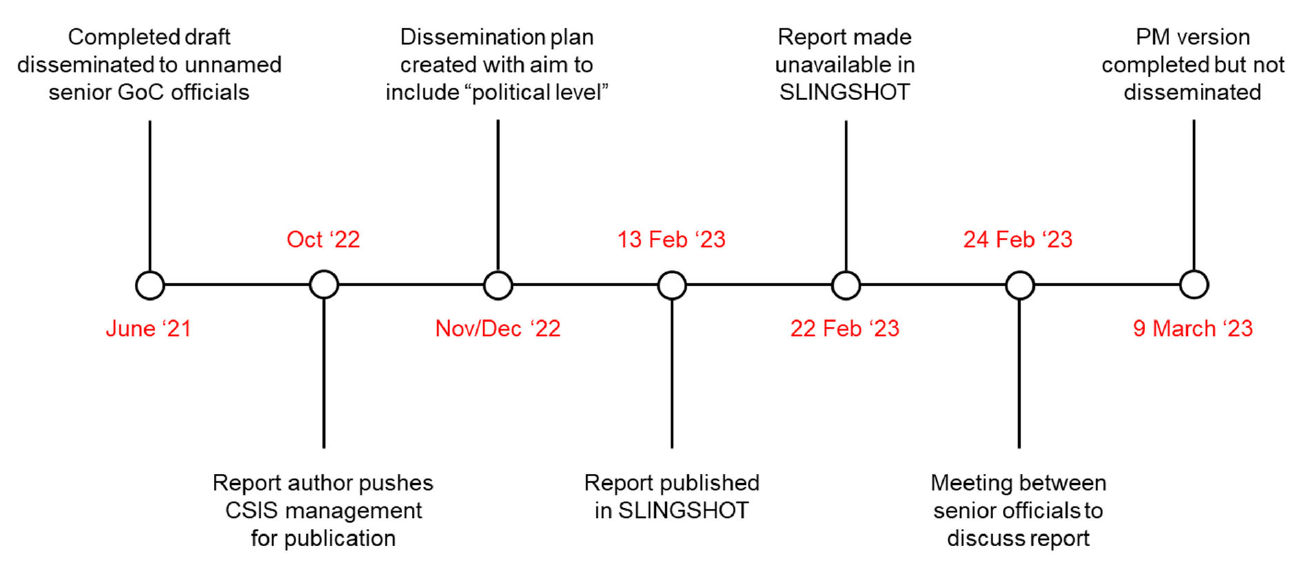

Figure 3. Key dates, dissemination of intelligence [**redacted**] in 2021 election

[**Figure has been edited to remove injurious information**]

Discussions about the product continued over the winter and spring of 2023, culminating in a decision to publish the product in July 2023 for CSIS-only distribution. As of November 2023, CSIS’s intelligence regarding the [**redacted**] potential involvement in foreign interference activities against the 2021 election has not been disseminated in a written intelligence product outside of CSIS, [**redacted**] years since it was initially collected.

Evaluating CSIS’s dissemination of intelligence

Finding 1: NSIRA found that CSIS’s dissemination of intelligence on political foreign interference during the 43rd and 44th federal elections was inconsistent. Specifically, in certain instances:

- The rationale for decisions regarding whether, when, and how to disseminate intelligence was not clear, directly affecting the flow of information; and

- The threat posed by political foreign interference activities was not clearly communicated by CSIS.

Finding 2: NSIRA found that CSIS’s dissemination and use of intelligence on political foreign interference was impacted by the concern that such actions could interfere, or be seen to interfere, in the democratic process.

Finding 3: NSIRA found that CSIS often elected to provide verbal briefings as opposed to written products in disseminating intelligence on political foreign interference during elections.

Finding 4: NSIRA found that there was a disconnect within CSIS between a region and National Headquarters as to whether reporting on political foreign interference was subject to higher thresholds of confidence, corroboration and contextualization for dissemination.

Within CSIS, political foreign interference is considered a subset of foreign interference more generally, while investigations touching on democratic institutions and processes are subsumed within broader procedures governing CSIS’s treatment of Canadian Fundamental Institutions. However, intelligence on political foreign interference presents several distinct challenges which are not addressed in policy or guidelines.

CSIS confronted a basic dilemma. On one hand, information about foreign interference in elections was a priority for the government, and CSIS’s collection apparatus was geared toward investigating political foreign interference. On the other, CSIS was sensitive to the possibility that the collection and dissemination of intelligence about the election could itself be construed as a form of election interference. A basic tension held: any action – including the dissemination of intelligence – taken by CSIS prior to or during an election must not, and must not be seen to, influence that election.

This dynamic was known within CSIS, but is not formally stated in policy or guidelines. Even more importantly, the specific criteria or considerations by which CSIS might balance these potentially competing imperatives are opaque. Absent their clear articulation, decisions appeared arbitrary. It was not always clear, particularly to those collecting intelligence, what the general rationale and/or policy guiding the dissemination of intelligence on political foreign interference was, let alone how that rationale/policy applied to specific decisions. Absent this clarity, frustration mounted (as one email opined, “if we’re not going to inform and share what we know, why are we collecting it?”).

Further, there was no clear basis to justify a decision to take action (including to outwardly report information), leading to a natural risk aversion on the part of decision-makers. Inevitably, this created frustration for those presenting decision-makers with options. Finally, because the rationale remained amorphous, there was no possibility of reasoned discussion and debate within CSIS regarding the proper calibration between the competing imperatives (to inform, but not to influence), nor any consistency in how they were balanced.

There were several instances in which intelligence was not placed into short, raw Intelligence Reports but instead held back for inclusion in longer, analytical pieces. The unique dynamics of political foreign interference may suggest that, in general, such analytical products are better vehicles for reporting collected information; as it stood, the decisions appeared ad hoc, to the point of suggesting a reluctance to place information in Intelligence Reports, as is CSIS’s typical dissemination process.

Likewise, the preference for oral briefings as the mode of dissemination during elections represented a deviation from CSIS’s most common dissemination practices. Whether justified or not, this deviation suggested special practices associated with political foreign interference in the absence of policy or procedures articulating what those special practices are or ought to be, while also creating challenges for tracking and documenting the provision of information.

This opacity with respect to process extended to approvals for counter political foreign interference activities. Whereas formal approval authority for a particular activity might reside at a certain level (for example Regional Director General), there was a recognition that the informal approval level for counter political foreign interference-related activities was the senior executive, including the Deputy Director of Operations or Director. Although not dictated by policy, it also became standard practice to “sensitize” or inform officials from PCO before CSIS could undertake certain counter-foreign interference activities.

For example, prior to the 2021 election, CSIS conducted Protective Security Briefings (PSB) in an effort to educate Members of Parliament (MPs) as to the threat of foreign interference. A regional desk planned a set of PSBs for a limited set of local MPs they determined to be at higher risk for being targets of political foreign interference. However, NHQ directed that the PSBs be paused, so that the [**dedicated unit in NHQ**] could devise a national PSB strategy along the same lines, based on lessons learned from a similar campaign prior to the 2019 election.

The national campaign was designed [**one sentence edited and one sentence deleted to remove injurious information. The sentences described CSIS methods and tactics**]. Such interest, if revealed, might be construed as inappropriate CSIS involvement in the democratic process.

Likely as a consequence of this sensitivity, the national campaign was further complicated by an extensive approvals process, which ultimately expanded to include sensitizing officials at PCO and Public Safety prior to conducting the briefings. In the end, the complexity and delay associated with the national campaign meant that it could not occur as planned. Instead, the region proceeded with as many of its initially planned PSBs as it could prior to the start of the writ period. Contact with MPs during the writ period was deemed inappropriate.

General sensitivities associated with counter-political foreign interference activities also influenced a [**one sentence edited and three sentences deleted to remove injurious information. The sentences described the objectives and implementation of a CSIS operational activity**]. This was a “conscious choice…due to political sensitivities” which, CSIS assessed, may have reduced the intended strategic impact of the [**CSIS operational activity**].

Finally, sensitivities also influenced the dissemination of specific intelligence products. Most prominently, as discussed above, intelligence collected in [**redacted**] 2021 was ultimately published in an intelligence product for CSIS-only distribution in July 2023. After extensive delay, revision, and consultation, a senior CSIS executive decided not to disseminate the product more widely (see Case Study 3).

At the core of the issues discussed above is a lack of clarity and communication pertaining to CSIS’s investigations of political foreign interference. Overall, the perception arose within CSIS that rules and decisions were being made, and frequently changed, absent a coherent strategy or guiding principles.

Intelligence is not evidence. Nor is it wild speculation, conjecture, or rumour. In theory, the threshold or standard for what intelligence is disseminated is uniform across the spectrum of threat-related activities. In practice, however, the cases examined demonstrate that, at the very least, there was a perception that standards were higher for intelligence related to political foreign interference. Although a senior CSIS executive told NSIRA that intelligence standards for political foreign interference were not different as compared to other threat-related information, they also outlined that there are sensitivities associated with disseminating intelligence about an individual involved in politics. For example, such information could have an impact on the career of that individual, including their ability to participate in democratic processes.

In some instances, regional collectors and analysts believed that CSIS NHQ (both [**dedicated unit in NHQ**] and senior management) placed too great an emphasis on “smoking guns” in terms of connecting activities directly to state actors.

Pushing for additional corroboration is a fundamental part of intelligence work. Standards, by their very definition, are meant to be uniform, and not differ by circumstance. Yet insisting that the push for corroboration or the standards for dissemination are the same for political foreign interference as compared to other reporting is untenable if it does not accurately reflect how decisions are made in practice. The failure to appreciate and account for the distinct nature of political foreign interference leads to confusion and consternation.

Political foreign interference often operates in the “grey-zone” between legitimate, overt political/diplomatic activity and covert, clandestine interference. Many of the consumers of intelligence on political foreign interference are familiar with political (in the case of ministers, members of parliament, and political parties) or diplomatic (for example officials at GAC) activities. This creates challenges for CSIS with respect to intelligence consumers in terms of making clear to consumers why the reporting is important and threat-related.

In short, CSIS is reporting about activities taking place in the milieu of the clients they serve. The practical implication is that any intelligence that is disseminated must sufficiently distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate activity. This can be difficult in practice, especially as the nature of PRC foreign interference in particular consists of the steady accumulation over time of activities and pressure that, in isolation and absent additional context, may appear innocuous, but in sum constitute a campaign to interfere in Canada’s democracy. PRC foreign interference is a growing rumble, not a loud bang.

There are several key shortcomings related to CSIS’s dissemination and use of intelligence on political foreign interference. First and foremost, CSIS has not clearly articulated its risk tolerance for counter political foreign interference activities. A defined risk tolerance allows those approving action to understand the parameters within which CSIS is comfortable operating.

Second, and relatedly, the approvals process for counter politicalforeign interference activities does not always reflect actual practice. For example, there are few clear directions and expectations in existing CSIS policy regarding when and why external entities – such as Public Safety and PCO – will be consulted prior to particular actions or activities, and none that account for the specific dynamics of counter political foreign interference activities noted above. Of note, in May 2023 the Minister of Public Safety issued a Ministerial Direction to CSIS on Threats to the Security of Canada Directed at Parliament and Parliamentarians, which outlines consultation principles in that specific context. However, the MD does not pertain to foreign interference against other democratic institutions.

Third, CSIS does not make explicit its thresholds for production and dissemination specifically related to intelligence on political foreign interference. That is, the level of confidence and corroboration required for collected information to be placed in an intelligence product, and the level of additional contextualization, such that the product can be disseminated to Government of Canada clients. The sensitivities associated with this type of intelligence, and the corresponding requirements for greater confidence and corroboration as compared to other types of security intelligence, should be acknowledged. For example, CSIS may wish to evaluate whether [**redacted**] criteria for Intelligence Report production are well suited for the specific nature of intelligence on political foreign interference.

What is needed, ultimately, is a comprehensive policy and strategy specifically pertaining to all aspects of how CSIS engages – investigates, reports about, and takes action against – threats of political foreign interference. This would bring coherence across all regions and NHQ, and generally facilitate greater understanding and communication between levels of the organization, from intelligence officers to analysts to senior management. At the same time, it would signal to Government of Canada stakeholders, and in particular senior decision-makers, that CSIS has carefully considered all aspects of political foreign interference, including its unique sensitivities, and is reporting and advising on those threats using rigorous standards and thresholds.

Canada is not alone in facing PRC political foreign interference. In the last several years, all of Canada’s Five Eyes partners (Australia, New Zealand, the US, and the UK) have publicly acknowledged the threat posed by PRC foreign interference to their respective democracies. There is a significant opportunity to leverage these shared experiences into best practices.

Recommendation 1: NSIRA recommends that CSIS develop, in consultation with relevant government stakeholders, a comprehensive policy governing its engagement with threats related to political foreign interference. This policy should:

- make explicit CSIS’s thresholds and practices for the communication and dissemination of intelligence regarding political foreign interference. This would include the relevant levels of confidence, corroboration, contextualization and characterization necessary for intelligence to be reported;

- clearly articulate CSIS’s risk tolerance for taking action against threats of political foreign interference;

- establish clear approval and notification processes (including external consultations) for all activities related to countering political foreign interference;

- make clear any special requirements or procedures that would apply during election/writ periods, as necessary, including in particular procedures for the timely dissemination of intelligence about political foreign interference; and,

- consider best practices from international partners (in particular the Five Eyes) regarding investigating and reporting about political foreign interference.

Part 2: The SITE Task Force and the CEIPP Panel

In the wake of well-documented Russian foreign interference in the 2016 US presidential election, the Government of Canada instituted a suite of measures meant to protect the integrity of federal elections. Three such measures are pertinent to the present review:

- Critical Election Incident Public Protocol (CEIPP) Panel. Established by Cabinet directive, the CEIPP is in place during the election period and administered by a panel of senior public servants. The Panel assesses security and intelligence information to determine whether to make a public announcement that “an incident or an accumulation of incidents has occurred that threatens Canada’s ability to have a free and fair election.” The Protocol was not invoked – that is, no public announcements were made – in either the 2019 or 2021 election.

- The Security and Intelligence Threats to Election (SITE) Task Force. The SITE Task Force is composed of representatives from CSIS, CSE, the RCMP, and GAC. The primary purpose of the Task Force is to provide coordinated intelligence reporting on threats to elections to the CEIPP Panel.

- G7 Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM). Established at the 2018 G7 meeting in Charlevoix, Canada’s RRM is housed within GAC, and focuses on foreign threats to democratic processes via threat analysis and reporting on online information manipulation activities by foreign state actors. The RRM team serves as GAC’s representative on the SITE Task Force.

These entities played significant roles with respect to the flow of intelligence on PRC foreign interference during the 2019 and 2021 elections. In essence, the SITE Task Force served – or was intended to serve – as a conduit for threat intelligence, while the Panel stood in receipt of that information, with a unique mandate to communicate, or not, with the Canadian public regarding the information it was provided.

Finding 5: NSIRA found that the SITE Task Force and the CEIPP Panel were not adequately designed to address traditional, human-based foreign interference. Specifically:

- The SITE Task Force focuses on threat activities during the election period, but traditional foreign interference also occurs between elections.

- Global Affairs Canada’s representation on the SITE Task Force focused on online foreign interference activities.

- The CEIPP Panel’s high threshold for a public announcement is unlikely to be triggered by traditional foreign interference, which typically targets specific ridings.

The structure and orientation of both the Task Force and the Panel were shaped by the imperative to protect elections against widespread and coordinated foreign interference occurring up to and including Election Day. That is, to protect Canadian elections from the type of foreign interference (largely online disinformation) witnessed in the US and elsewhere.

At the same time, the security and intelligence community recognized that human-based, so-called “traditional” foreign interference had been, and continued to be, the most significant threat to Canadian democratic processes and institutions. For example, the SITE Task Force’s 2021 threat overview noted that foreign interference actors predominately used human-based tactics “partly as a result of the way that Canada conducts its elections…but also due to the efficacy of HUMINT-based influence operations as compared to cyber activities given the structure of the Canadian electoral system.” Overall, the predominance of traditional foreign interference was known prior to 2019, and subsequent experience reinforced this perception.

Despite this recognition, the parameters of the SITE Task Force and the CEIPP Panel are not aligned with the nature of the threat stemming from traditional foreign interference.

In a post-election Panel debrief, a Panel member noted that a major, widespread and successful interference campaign did not occur and that the election had been “clean” despite “some stuff” occurring. The foreign interference in a specific riding [**redacted**], according to this panelist, was “not material to the election” and therefore not of direct concern to the Panel’s remit. At the same meeting, the CSIS Director asserted that the “strongest case” of PRC foreign interference during the election were the events cited in this riding. The Director also lamented that “the machine” (the SITE Task Force and the CEIPP Panel) was not set up to address foreign interference outside of the election period.

Unlike broad patterns or campaigns (such as widespread online disinformation), intelligence on traditional foreign interference in elections is typically granular and specific, pertaining to the activities of individuals in particular ridings. Assessing the impact of those activities at the riding-by-riding level requires receiving and analyzing all relevant intelligence on an ongoing basis. This is doubly challenging given the short time frame in which elections occur.

Similarly, a core feature of traditional foreign interference is that it takes place over the long term, and is not confined simply to election periods. While the SITE Task Force is in continual operation, its capacity and operational tempo is reduced outside election periods. Moreover, its focus remains on the election period, and on the outcome/integrity of the vote on Election Day. These features undermine the Task Force’s ability to fully address traditional foreign interference, which is not confined to election periods and threatens democratic institutions more broadly.

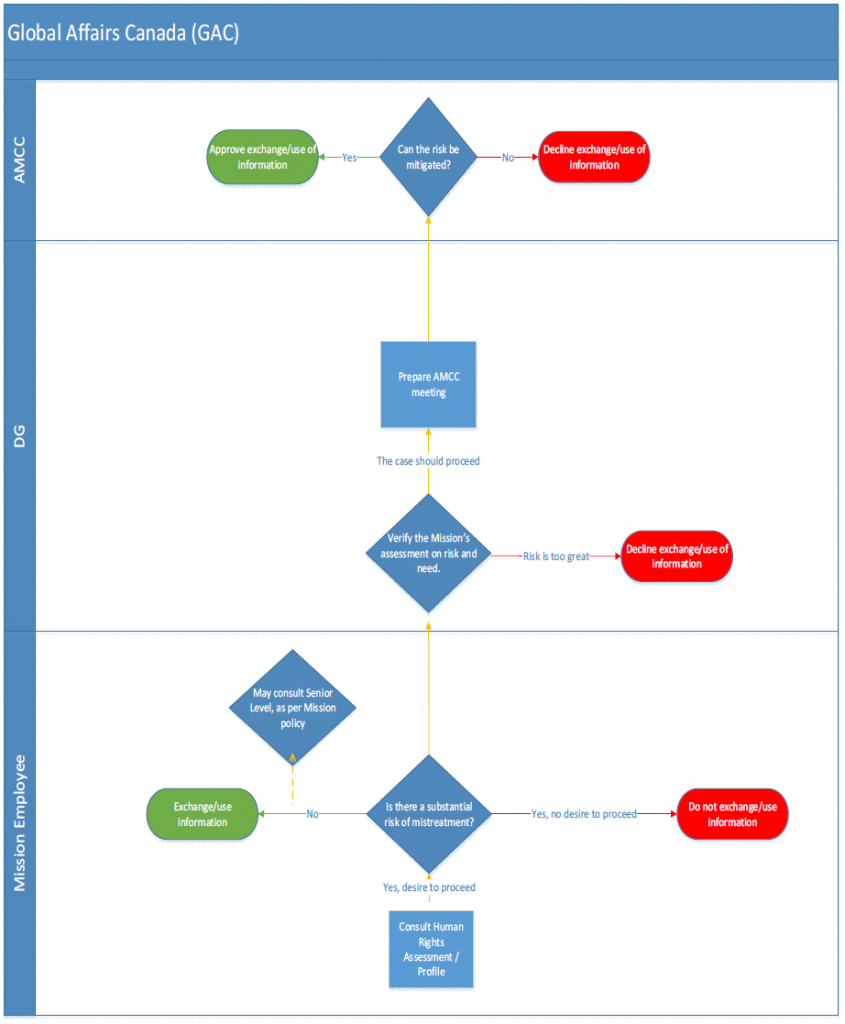

Consider also the inclusion of the RRM team as GAC’s representation on the Task Force. The RRM is specifically geared toward the online space, and monitoring social media for potential foreign interference activities, including the spreading and amplification of disinformation. By contrast, GAC’s capacity to analyze intelligence related to, and devise potential responses against, traditional foreign interference is not sufficiently represented on the Task Force. Traditional foreign interference frequently runs through [**redacted**]. There is a significant role for GAC to play in terms of response (for example issuing démarches or expelling diplomats) and interpretation (for example on the difference between foreign interference and legitimate diplomatic activity) that extends beyond the RRM team’s specific remit.

Finally, the CEIPP Panel’s threshold for a public announcement as to the integrity of the election is geared toward broad, systematic foreign interference such as that constituted by online disinformation campaigns or other cyber activities. This means that, in practice, the public may hear nothing from the Panel, even as significant foreign interference takes place, so long as that interference remains below what is recognized to be an incredibly high threshold.

A lack of public communication – transparency – creates several potential issues and can be interpreted in multiple ways. If information about specific foreign interference attempts emerges following the election, no communication during the election may be interpreted as a lack of action, or lack of willingness to take action, on the part of the government. If no such information emerges, the lack of communication, and associated implication that the integrity of the election was not threatened by foreign interference, may give a false impression as to the level of foreign interference that occurred.

Recommendation 2: NSIRA recommends that the SITE Task Force align its priorities with the threat landscape, including threats which occur outside of the immediate election period.

Recommendation 3: NSIRA recommends that Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and the Privy Council Office ensure that GAC’s representation on the SITE Task Force leverages the department’s capacity to analyze and address traditional, human-based foreign interference, in addition to the online remit of the Rapid Response Mechanism Team.

Recommendation 4: NSIRA recommends that the Privy Council Office empower the CEIPP Panel to develop additional strategies to address the full threat landscape during election periods, including when threats manifest in specific ridings.

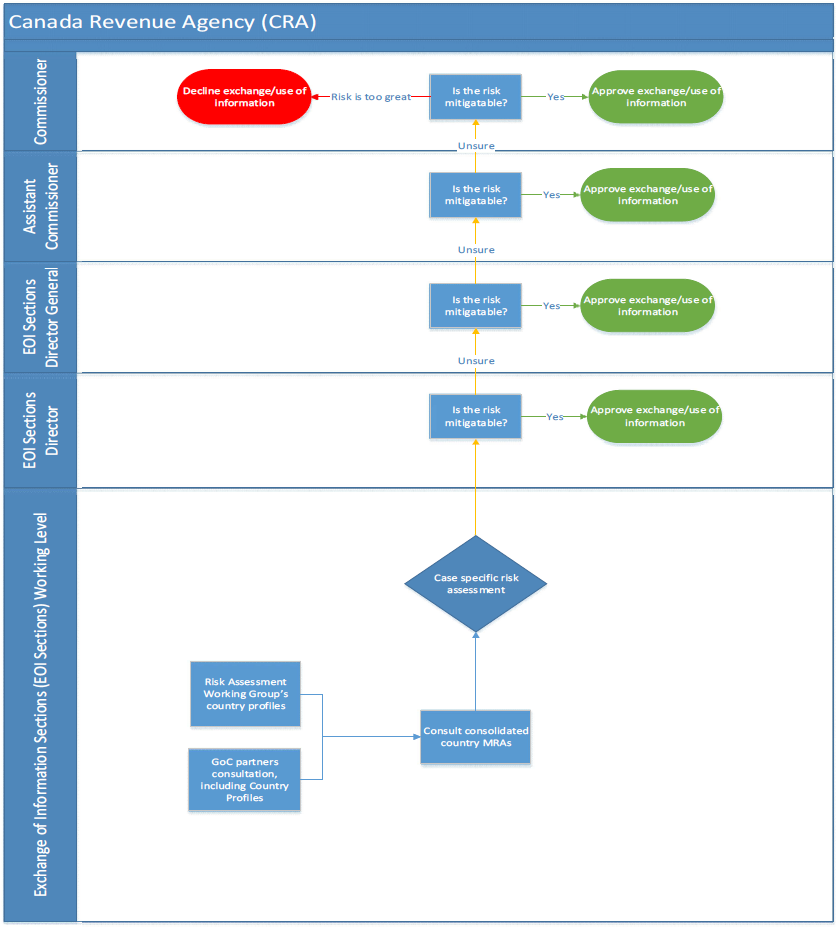

Part 3: The flow of intelligence on PRC foreign interference

This final section of the report steps away from the election-specific context to consider the flow of intelligence on PRC foreign interference between 2018 and 2023 more broadly. As noted, political foreign interference is everywhere and all the time. The intelligence community collects intelligence on PRC political foreign interference on an ongoing basis. This intelligence is shared both horizontally within the community and vertically to senior decision makers, including elected officials.

The responsible sharing of intelligence between organizations is an important feature of a healthy security and intelligence community. While sensitivities, particularly of sources and methods, make the classification of material necessary, and the need-to-know principle further conscribes the circle of individuals who may view certain information, the cross-fertilization of intelligence enhances the ability of organizations to inform decision-makers from the perspective of their particular mandates.

Finding 6: NSIRA found that the limited distribution of some CSIS and CSE intelligence to senior officials-only reduced the ability of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Global Affairs Canada, and the Privy Council Office to incorporate that intelligence into their analysis.

With respect to intelligence on PRC foreign interference, reporting from the core “collectors” (CSIS and CSE) informed intelligence analysis by the other security and intelligence organizations under review (GAC, the RCMP, and PCO).

However, this cross-fertilization was not without issues. For example, a GAC assessment from late August 2021 discusses CSIS intelligence indicating PRC political interference but omits other, specific CSIS intelligence directly relevant to GAC’s assessment. Given the sensitivity of the intelligence, however, the CSIS Intelligence Report pertinent to, but missing from, GAC’s analysis was sent to “named recipients only”, meaning that although senior officials at GAC had access to it, analysts within GAC’s Intelligence Bureau did not. This dynamic was typical of many Intelligence Reports produced and disseminated on PRC political foreign interference, making it challenging, on occasion, for recipient organizations to incorporate that intelligence into their own analytical assessments.

In the case of the expulsion of PRC diplomat Zhao Wei in May 2023, [**redacted**]. (At the same time, disagreements persisted between CSIS and GAC as to what does or does not constitute “legitimate diplomatic activity”.)

A similar dynamic pertained to CSE SIGINT on PRC foreign interference. While many End Product Reports – CSE’s standard intelligence product – were incorporated into GAC, PCO, and RCMP analysis, some of the most pertinent intelligence was classified at a level which significantly limited its distribution, due to the sensitivity of the collection method. This intelligence was available to a limited number of individuals (including senior officials) within government who possessed the requisite indoctrination.

There is a balance to be struck between protecting sensitive information by limiting its distribution and ensuring pertinent information is shared to inform intelligence analysis and potential action across the government. NSIRA did not assess whether specific intelligence products were or were not “over-classified”, other than to note that decisions regarding classification have direct consequences for dissemination.

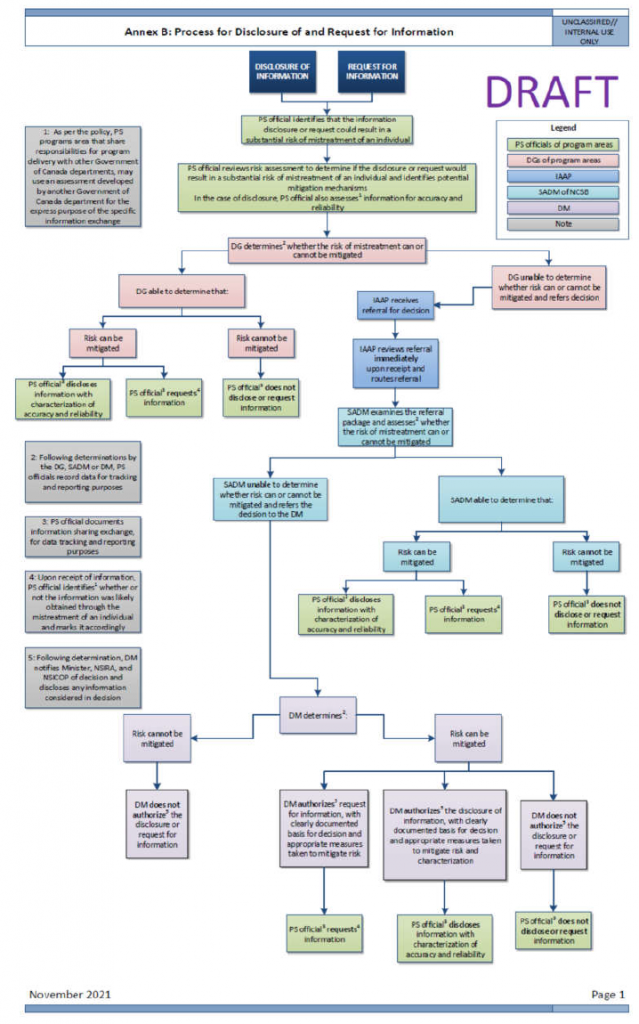

Finding 7: NSIRA found that CSIS and Public Safety did not have a system for tracking who received and read specific intelligence products, creating unacceptable gaps in accountability.

Intelligence is shared within the Government of Canada in a multitude of ways. CSIS intelligence in particular may be shared directly by secure email, or by uploading products to platforms such as the Canadian Top Secret Network (CTSN) and CSE’s SLINGSHOT repository. Hard copies of products can be disseminated via CSE’s Client Relations Officer (CRO) program, with embedded officers serving clients in various departments and agencies. Some departments, such as GAC and Public Safety, have their own in-house intelligence dissemination officers. Secure emails with intelligence products in attachment provide instructions to contacts regarding who in the department should receive the product (for example Deputy Ministers and Ministers).

During the review period, CSIS lacked the ability to definitively track who had received and read its intelligence. Partly this was a consequence of the internal tracking systems of the various recipient departments, who may not have comprehensively captured this data. In the end, however, it is incumbent on CSIS, as the originator of sensitive information, to control and document access.

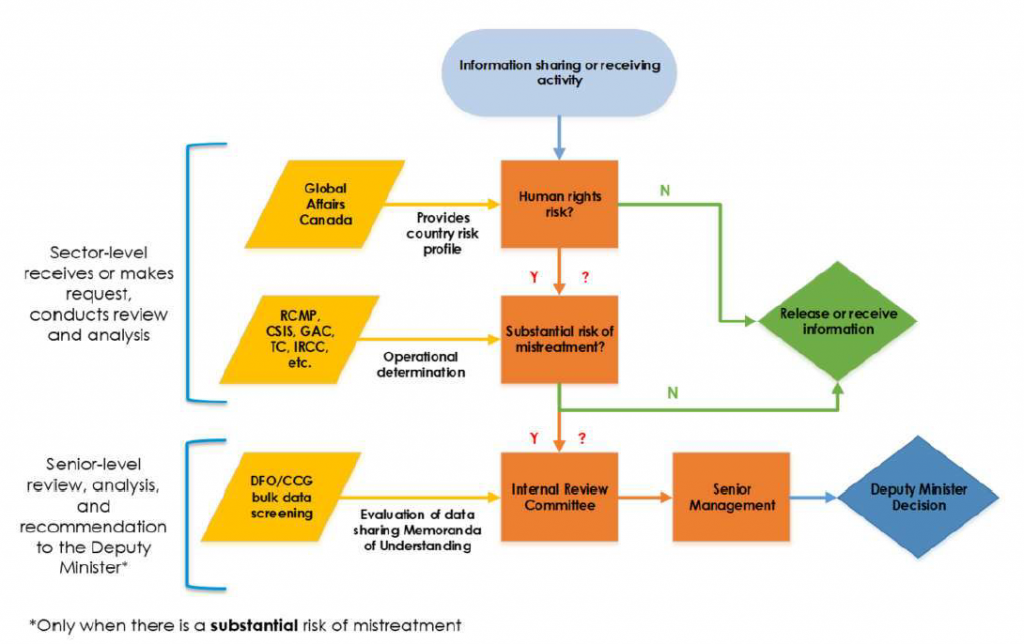

Intelligence on the PRC targeting of a Member of Parliament

The consequences of not knowing who has read what manifested in the controversy regarding intelligence related to the PRC’s targeting of a sitting Member of Parliament.

In May 2023, media reporting revealed that the Government of Canada had intelligence that a Member of Parliament and his family members had been “targeted” for sanction by the PRC.

The media and public conversation centered around two CSIS products. First, a July 2021 CSIS Intelligence Assessment [**sentence edited to remove injurious information. The sentence described the contents of the Intelligence Assessment, which included intelligence related to PRC foreign interference activities**]. And second, a May 2021 “Issues Management Note” sent by CSIS to senior government officials to inform them that CSIS would be briefing two MPs (including the Member of Parliament in question) on PRC threat-activities against them.

The focus on these two products was misplaced. Neither was the mechanism through which the Minister and Deputy Minister of Public Safety were initially meant to be informed of the PRC’s threat activities against the Member of Parliament and his family.

Rather, [**prior to May 2021**] there was [**CSIS intelligence**] related to the PRC’s targeting of the Member of Parliament. [**CSIS intelligence was**] sent to named recipients lists which included the Deputy Minister and Minister of Public Safety. [**CSIS intelligence**] was disseminated by secure email directly to individuals and departmental contacts. The departmental contacts were directed to provide the information to named senior individuals, including the Minister of Public Safety, as these officials would not have had direct access to secure email. Additional named recipients of [**CSIS intelligence**] included the NSIA, the Clerk of the Privy Council, the Deputy Minister of National Defence, the Foreign and Defence Policy Advisor, the Chief of CSE, and other senior officials at GAC, PCO, DND, CSE, and Public Safety.

CSIS disseminated [**redacted**] 2021. [**Sentence deleted to remove injurious information. The sentence summarized CSIS intelligence**] Public Safety indicated to NSIRA that [**CSIS intelligence**] was distributed internally the week of [**redacted**] 2021 and that the “only indication is that it was sent to senior management.”

Next, on [**redacted**] 2021, CSIS disseminated [**redacted**] containing intelligence that [**Sentence edited to remove injurious information. The sentence summarized CSIS intelligence**] Public Safety indicated to NSIRA that [**CSIS intelligence**] was distributed internally the week of [**redacted**], 2021 and that the “only indication is that it was sent to the Minister.”

Finally, on [**redacted**] 2021, CSIS disseminated [**Sentence edited to remove injurious information. The sentence summarized CSIS intelligence**] The information was required urgently as [**redacted**]. Public Safety indicated to NSIRA that it had no record of receiving this [**CSIS intelligence**].

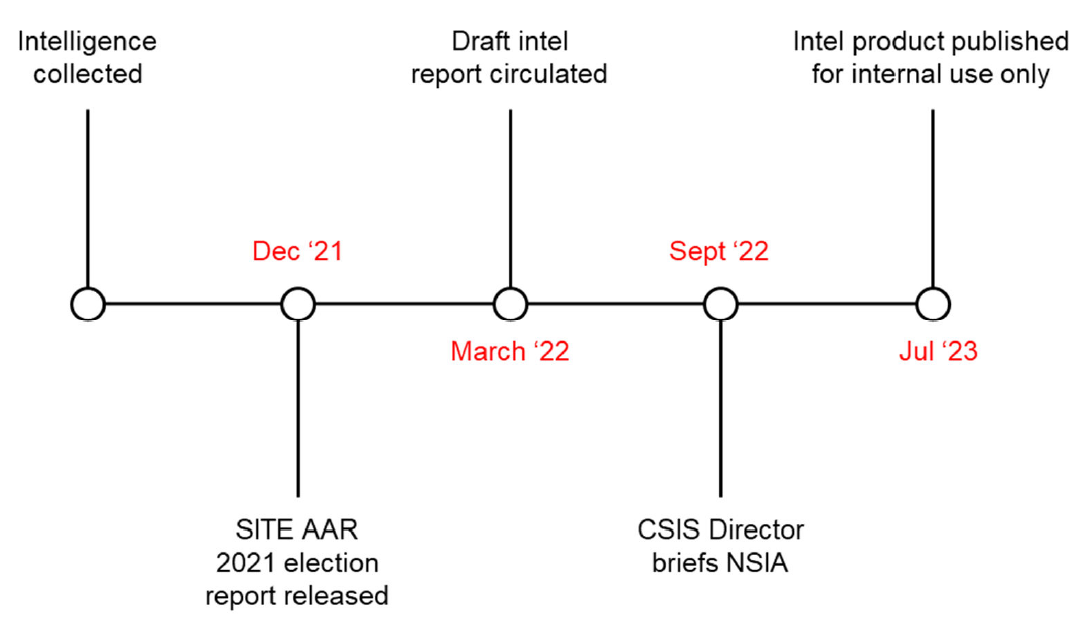

Figure 4. Key dates, dissemination of intelligence on targeting of a federal MP

[***Figure has been edited to remove injurious information***]

As noted above, Public Safety stated that at least one [**piece of CSIS intelligence**] was provided to the Minister of Public Safety, likely as part of a weekly reading package in [**redacted**] 2021. This would have preceded by several months both the Issues Management Note of May 2021 and the Intelligence Assessment of July 2021. There is no indication that [**redacted**] was provided to the minister, despite the fact that he was a named recipient on the distribution list.

Most problematic is Public Safety’s inability to account for [**redacted**]. In the wake of the public controversy in 2023, CSIS and Public Safety compiled a chronology of relevant events. Public Safety suggested that perhaps “human error” accounted for the gap in its records, and that the file may have accidently been deleted. Further, the CSIS Director and the NSIA requested that the joint CSIS-PS chronology reflect the fact that “the distribution of a document does not indicate that a document was received or read by the recipient.” This notion – of a possible black hole between the dissemination of a critical product and its receipt on the other end – is a demonstrably unacceptable state of affairs.

As this case makes clear, it is incumbent on CSIS to implement a system that comprehensively tracks the dissemination and receipt of its own intelligence, including, in the case of certain prioritized intelligence, who has read specific products. Prioritized intelligence could include highly sensitive and urgent intelligence, for example regarding threats of foreign interference against elections or other key democratic institutions or processes.

Recommendation 5: NSIRA recommends that, as a basic accountability mechanism, CSIS and Public Safety rigorously track and document who has received intelligence products. In the case of highly sensitive and urgent intelligence, this should include documenting who has read intelligence products.

At the same time, tracking who has read what is not a panacea. There must be interest on the part of consumers for the intelligence they receive, and an understanding as to how the intelligence can support the fulfillment of their responsibilities.

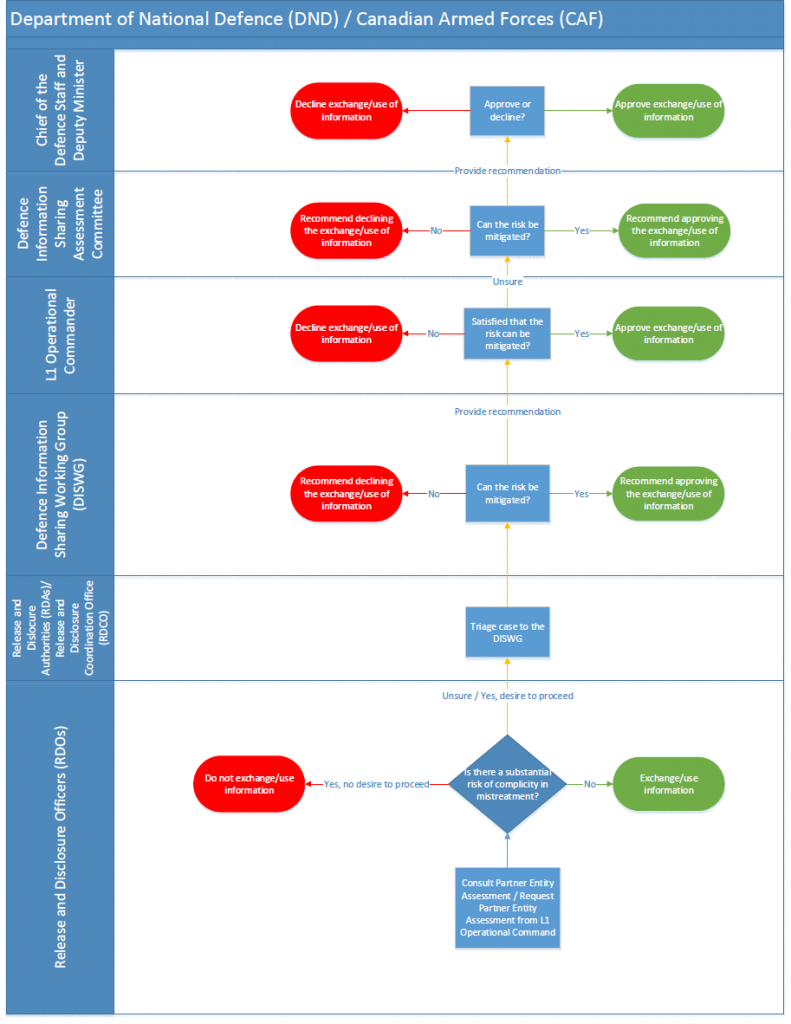

Finding 8: NSIRA found that the dissemination of intelligence on political foreign interference from 2018 to 2023 suffered from multiple issues. Specifically:

- Intelligence consumers did not always understand the significance of the intelligence they received nor how to integrate it into their policy analysis and decision-making;

- There was disagreement between intelligence units and senior public servants as to whether activities described in specific intelligence products constituted foreign interference or legitimate diplomatic activity.

Finding 9: NSIRA found that there was disagreement between senior public servants and the NSIA as to whether intelligence assessments should be shared with the political executive. Ultimately, the NSIA’s interventions resulted in two products not reaching the political executive, including the Prime Minister.

Finding 10: NSIRA found that the NSIA’s role in decisions regarding the dissemination of CSIS intelligence products is unclear.

In multiple briefings and interviews from across the community, NSIRA heard about the challenge of articulating the “so-what” in intelligence analysis. Part of this challenge stems from so-called “literacy gaps” between the intelligence and policy communities; that is, low policy literacy on the part of intelligence analysts, and low intelligence literacy on the part of policy analysts or policymakers. This gap can create confusion as to what intelligence is for, and what can be done about the threats that intelligence describes.

Consider for example the emphasis on “actionable” intelligence or “recommendations” for action that consumers look to the intelligence community to provide. Not all intelligence will come with these characteristics. Instead, intelligence may be provided for information and awareness purposes only (including to increase the salience of important trends and threats). Intelligence analysts explained that, ultimately, it is the consumers of intelligence who have the mandate to take action (including to shape strategic policy), while the analyst’s job is to provide them with information that best allows them to do so.

The core function of the intelligence process is the provision of intelligence analysis to policymakers. In-depth analysis – the weaving together of disparate data into a coherent narrative, with judgments and assessments as to the implications of the information presented – is the purview of dedicated units within security and intelligence agencies, such as CSIS’s Intelligence Assessment Branch (IAB) and PCO’s Intelligence Assessment Secretariat (IAS). It is the job of analysts to contextualize collected intelligence for senior consumers.

The dissemination of intelligence to the political executive can occur verbally, in both formal and informal briefings, by senior public servants, such as Deputy Ministers and, in the case of the Prime Minister, the NSIA. At the same time, written analytical products can provide the political executive with key analysis and pressing takeaways regarding threats to the security of Canada.

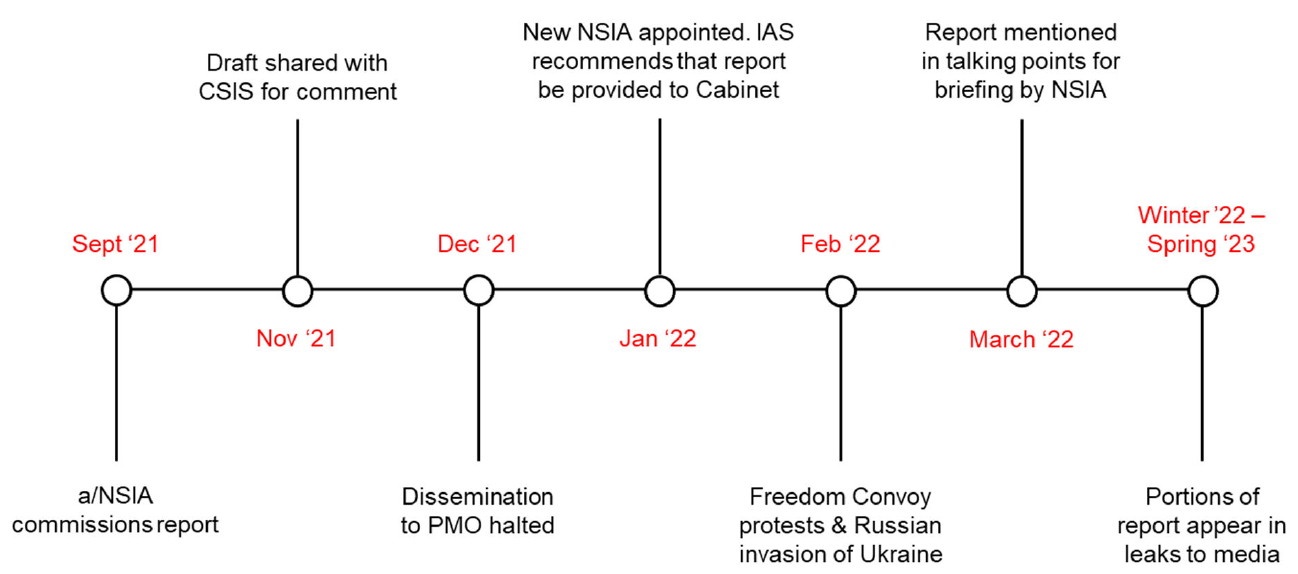

PCO “Special Report”

In the fall of 2021, the acting NSIA received a series of briefings from PCO IAS on PRC foreign interference. In order to understand more about the issue the acting NSIA commissioned a “Special Report” that would combine foreign intelligence (the traditional purview of IAS) with domestic, security intelligence (CSIS’s domain).