- Executive Summary

- Authorities

- Introduction

- FINDINGS

- Reporting and Framework Updates

- Referrals to Deputy Head

- Case Triage

- Initial Case Triage Category 1: Case-by-Case

- Initial Case Triage Category 2: Informed by Country Assessment Rating

- Case Escalation

- Consistency in Implementation Across Departments

- Box 1: A divergent decision-making process

- Mitigation Measures

- CONCLUSION

- Annex A: Findings

- Annex B: Canada Border Services Agency

- Annex C: Canada Revenue Agency

- Annex D: Communications Security Establishment

- Annex E: Canadian Security Intelligence Service

- Annex F: DFO

- Annex G: Department of National Defence/Canadian Armed Forces

- Annex H: FINTRAC

- Annex I: Global Affairs Canada

- Annex J: IRCC

- Annex K: Public Safety

- Annex L: Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Annex M: Transport Canada

Date of Publishing:

Executive Summary

The Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACA or Act) and its associated directions seek to prevent the mistreatment of any individual as a result of information exchanged between a Government of Canada department and a foreign entity. At the heart of the directions is the consideration of substantial risk, and whether that risk, if present, can be mitigated. To do this, the Act and the directions lay out a series of requirements that need to be met or implemented when handling information. This review covers the implementation of the directions sent to 12 departments and agencies from their date of issuance, January 1, 2020, to the end of the previous calendar year, December 31, 2020. It was conducted under subsection 8(2.2) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act (NSIRA Act), which requires NSIRA to review, each calendar year, the implementation of all directions issued under ACA.

This was the first ACA review to cover a full calendar year. Many of the reviewed departments noted that the pandemic impacted their information sharing activities, thus impacting the number of cases requiring further review as per the ACA. As such, NISIRA found that from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020, no cases under the ACA were escalated to deputy heads in any department.

While NSIRA was pleased with the considerable efforts made by many departments new to ACA in building their frameworks, Canada Boarder Services Agency (CBSA) and Public Safety did not finalize their policy frameworks in support of the Directions received under the ACA for the review period.

As part of the review, NSIRA examined the case triage process of all twelve departments. NSIRA found that even when departments employ similar methodologies and sources of information to inform their determination of whether or not a case involving the same country of concern should be escalated, significant divergences in the evaluation of risk and the required level of approval emerge.

A case sent to both GAC and CSIS was reviewed by NSIRA for its implications under the ACA. While the information was ultimately not shared with the requesting foreign entity, nonetheless, NSIRA found that the risk of mistreatment was substantial and the decision should have been referred to the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs as the accountable deputy minister for this request.

Mitigation measures used by departments were also reviewed this year, since they are an integral part in the information sharing process for departments. NSIRA observed that there are gaps in departments’ ability to verify whether a country or entity has actually complied with caveats or assurances because of the difficulty in tracking compliance to mitigation measures.

NSIRA believes that it is now in a position to conduct in-depth case study assessments of individual departments’ adherence to the ACA and Directions, irrespective of whether or not a department reported any cases to its deputy head. Finally, future reviews will follow up on the ongoing implementation of NSIRA’s past recommendations.

In keeping with NSIRA’s 2020 Annual Report which emphasized the implementation of a “trust but verify” approach for assessing information provided over the course of a review, NSIRA continues to work on various verification strategies with the Canadian intelligence community. However, due to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, implementation of verification processes was not possible across all twelve departments which fall under the ACA. Notwithstanding, the information provided by departments has been independently verified by NSIRA through documentation analysis and meetings with department subject matter experts, as warranted. Further work is underway to continue developing an access model for the independent verification of information relevant to ACA considerations.

Authorities

This review was conducted under subsection 8(2.2) of the NSIRA Act, which requires NSIRA to review, each calendar year, the implementation of all directions issued under the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACA or the Act).

Introduction

Review background

Departments and agencies in the Government of Canada routinely share information with a range of foreign entities. However such practices can sometimes bring into play a risk of mistreatment for individuals who are the subjects of these exchanges or other individuals. It is therefore incumbent upon the Government of Canada to evaluate and mitigate the risks that this sharing entails.

In 2011, the Government of Canada implemented a general framework for Addressing Risks of Mistreatment in Sharing Information with Foreign Entities. The aim of the framework was to establish a coherent approach across government when sharing with and receiving information from foreign entities. Following this, Ministerial Direction was issued to applicable departments in 2011 (Information Sharing with Foreign Entities), and then again in 2017 (Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities).

On July 13, 2019, the ACA came into force. The preamble of the Act recognizes Canada’s commitments with respect to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and Canada’s international legal obligations on prohibiting torture and other cruel and inhumane treatment. The Act also recognizes that information needs to be shared to enable the Government to fulfill its fundamental responsibility to protect Canada’s national security and the safety of Canadians.

On September 4, 2019, pursuant to section 3 of the ACA, the Governor in Council (GiC) issued written directions (Orders in Council (OiCs) or Directions) to the deputy heads of 12 departments and agencies. This added six new Canadian entities in addition to those that were already associated with the 2011 and 2017 Directions.

This report is NSIRA’s first full year assessment of the implementation of the Directions issued under ACA for the 2020 calendar year. The review builds upon two previous reviews conducted in respect of avoiding complicity in mistreatment. The first was in respect to the 2017 Ministerial Directions, while the second assessed the Directions issued under the ACA, but was limited to the four months from when the Directions were issued to the end of the 2019 calendar year.

ACA and Directions

The ACA and the Directions issued under its authority seek to prevent the mistreatment of any individual due to the exchange of information between a Government of Canada department or agency and a foreign entity. The Act and the Directions also aim to limit the use of information received from a foreign entity that is likely to have been obtained through the mistreatment of an individual.

Under the authority of subsection 3(1) of the Act, the Directions issued to the 12 departments and agencies are near identical in language and focus on the three aspects of handling information when interacting with a foreign entity: the disclosure of information, the requesting of information, and the use of any information received.

In regards to disclosure of information, the Directions state:

If the disclosure of information to a foreign entity would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual, the Deputy Head must ensure that the Department officials do not disclose the information unless the officials determine that the risk can be mitigated, such as through the use of caveats or assurances, and appropriate measures are taken to mitigate the risk.

With respect to requesting information, the Directions read as follows:

If the making of a request to a foreign entity for information would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual, the Deputy Head must ensure that Department officials do not make the request for information unless the officials determine that the risk can be mitigated, such as through the use of caveats or assurances, and appropriate measures are taken to mitigate the risk.

Lastly, as it relates to the use of information, the Directions provide:

The Deputy Head must ensure that information that is likely to have been obtained through the mistreatment of an individual by a foreign entity is not used by the Department

(a) in any way that creates a substantial risk of further mistreatment;

(b) as evidence in any judicial, administrative or other proceeding; or

(c) in any way that deprives someone of their rights or freedoms, unless the Deputy Head or, in exceptional circumstances, a senior official designated by the Deputy Head determines that the use of the information is necessary to prevent loss of life or significant personal injury and authorizes the use accordingly.

The consideration of substantial risk figures prominently in subsection 3(1) of the Act as well as the Directions. In considering whether to disclose or request information, a department must determine whether a substantial risk is present and if so whether it can be mitigated. As noted in the previous reviews on information sharing, the ACA does not define “substantial risk”. Departments refer to a definition of this term as set out in the 2017 Ministerial Directions as a general starting point when conducting assessments under the ACA. The 2017 Ministerial Directions define substantial risk as:

‘Substantial risk’ is a personal, present and foreseeable risk of mistreatment that is real and is based on something more than mere theory or speculation. In most cases, the test of a substantial risk of mistreatment would be satisfied when it is more likely than not there would be mistreatment; however, in some cases, particularly where the risk if of severe harm, the standard of substantial risk may be satisfied at a lower level of probability.

Based on the outcome of these determinations, the decision may be to approve, deny, or elevate to the Deputy Head for his or her consideration. Substantial risk is also contemplated in the consideration of the use of information received from a foreign entity. If it is evaluated that the information was likely obtained from the mistreatment of an individual, the department is prohibited from using the information in any way that creates a substantial risk of further mistreatment.

Throughout the process to determine whether to disclose or use information, the Directions require that the accuracy, reliability, and limitations of use of all information being handled are appropriately described and characterized.

Additionally, reporting requirements are found at sections 7 and 8 of the Act as well as within the Directions. Among these requirements, the Minister responsible for the department must provide a copy of the department’s annual report in respect of the implementation of the Directions during the previous calendar year as soon as feasible to NSIRA, the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICoP) and, if applicable, the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission (CRCC) for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Reporting requirements as articulated in the Directions oblige the reporting of decisions which were considered by the Deputy Head in regards to disclosure, requesting of information, or authorizing use of information that would deprive someone of their rights or freedoms be made as soon as feasible to the responsible Minister, NSIRA, and NSICoP.

Review Objectives and Methodology

The review period was January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020. The objectives of this review included:

- Following-up on departments’ implementation of the directives received under the ACA;

- Assessing departments’ operationalization of frameworks/processes that enable them to meet the obligations set out in the ACA and directives; and

- Assessing coordination and consistency in implementation across applicable departments.

Additionally, NSIRA evaluated all twelve ACA member departments’ ‘case triage’ frameworks (i.e., the combination of policy assessment criteria and a pre-determined ‘escalation ladder’ for cases that require higher levels of managerial approvals). Refer to annexes B to M that provide additional details on each departments’ triage process. Finally, NSIRA reviewed the use and policies around departmental mitigation measures.

FINDINGS

Reporting and Framework Updates

As per the Act, all twelve departments fulfilled their obligations to report to their respective ministers and NSIRA on progress made in operationalizing frameworks and identifying cases escalated to the deputy head level.

Of the nine departments who had reported to NSIRA last year that they had finalized frameworks, all continued to refine assessment protocols over the 2020 review period. Based on submissions to NSIRA, TC has developed a corporate policy to highlight the department’s ACA-related requirements. However, CBSA and PS had yet to finalize their ACA policy. As a result, employees may not have adequate and up to date guidance on how to make determinations related to the ACA.

NSIRA Finding #1: NSIRA found that CBSA and PS did not finalize their policy frameworks in support of Directions received under the ACA over the review period.

Referrals to Deputy Head

The Directions specify that when departmental officials are unable to determine whether the risk of mistreatment arising from a disclosure of or request for information can be mitigated, the matter must be referred to the Deputy Head. The Directions also require the Deputy Head, or in exceptional circumstances a senior official designated by the Deputy Head, to determine the matter where the use of information that is likely to have been obtained through mistreatment of an individual by a foreign entity would in any way deprive an individual of their rights or freedoms and the use of this information is necessary to prevent loss of life or significant injury. In 2020, no cases were escalated to the deputy head level. NSIRA sought clarification on the absence of cases referred; the most common reason provided by departments for this outcome was that cases were either mitigated before deputy head involvement and/or this was a result of an overall reduction in the number of foreign information exchanges generally due to the ongoing pandemic.

NSIRA Finding #2: NSIRA found that from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020, no cases under the ACA were escalated to deputy heads in any department.

Case Triage

Typically, when departments are making ACA applicability decisions, they employ varying “case triage” processes, that is, the combination of policy assessment criteria and a pre-determined ‘escalation ladder’ for cases that require higher levels of managerial assessment. NSIRA closely evaluated all twelve ‘case triage’ frameworks of the departments subject to the ACA (Refer to Annex B-M). In carrying out this work, NSIRA noted some issues in the implementation of triage systems; for example, there were instances of not having one designed and of information being outdated.

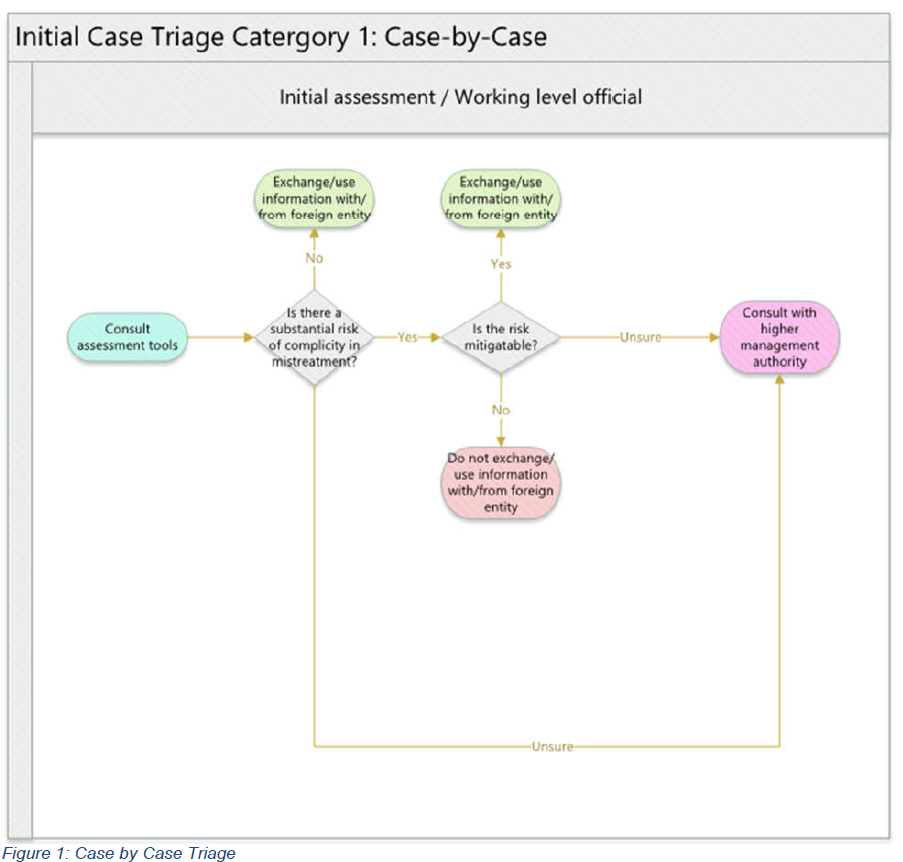

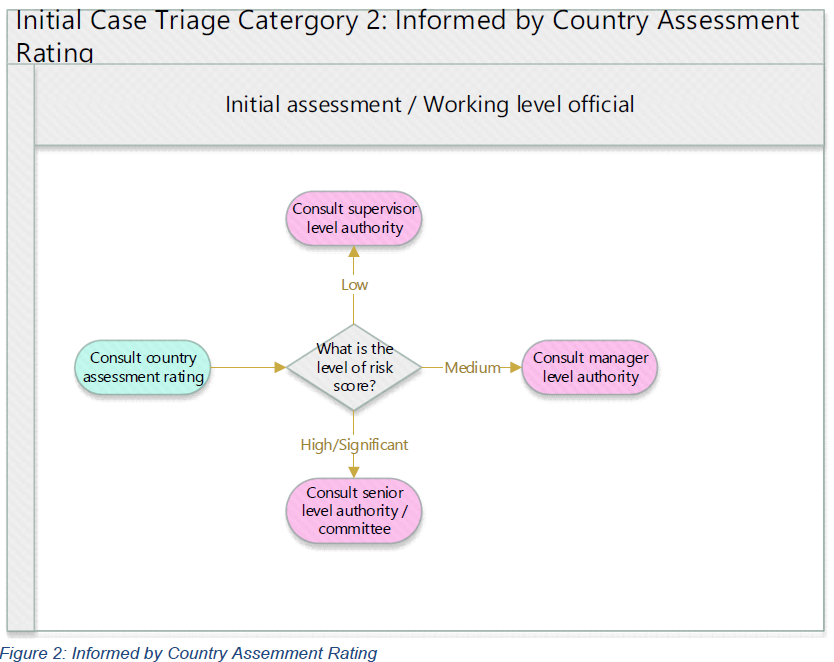

NSIRA observed that there were two main types of initial case triage processes: case-by-case, where the framework places the onus on the working level official to first make determinations based on policy assessment tools, relevant training, and individual experience; and country assessment rating, which emphasizes the initial use of a country-based risk level that may trigger case escalation. A country assessment rating is a representation of the assessed risk of mistreatment associated to a country, based on a number of criteria and often derived from a range of sources.

Initial Case Triage Category 1: Case-by-Case

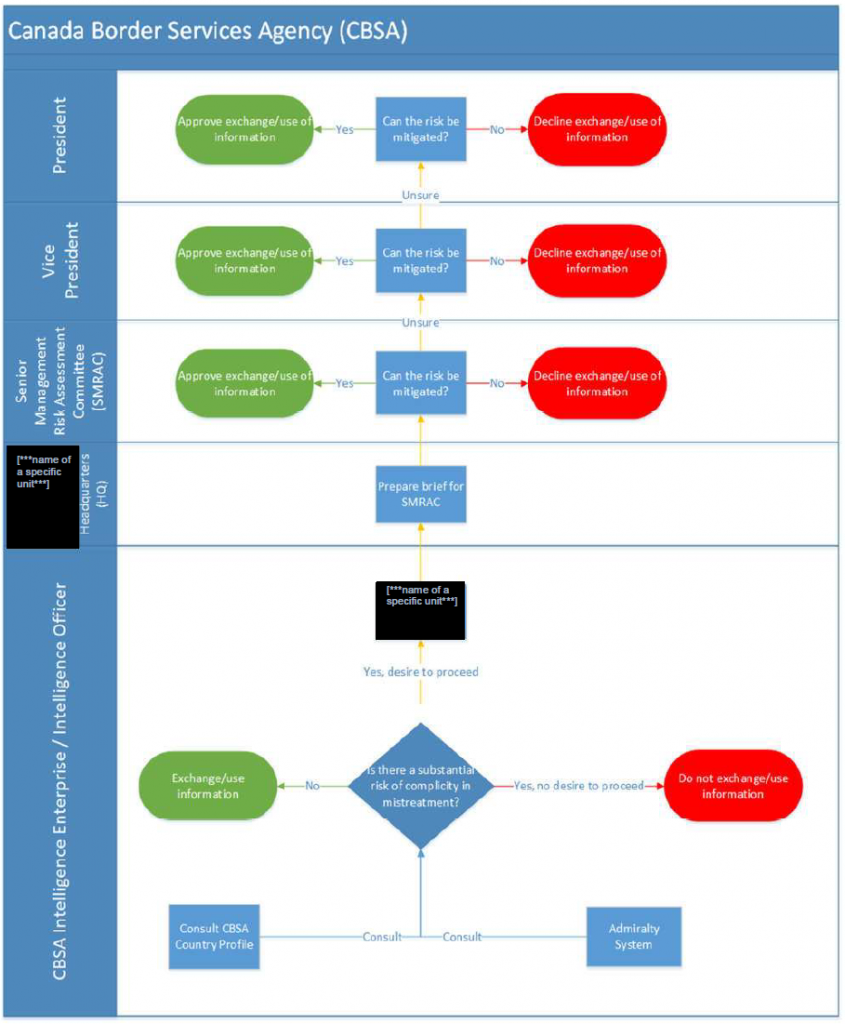

All departments use working level officials to determine whether there is a risk of mistreatment. When a working level officials’ assessment is inconclusive as to whether a substantial risk of mistreatment exists, they will defer the decision to a higher management authority. NSIRA has developed Figure 1 to illustrate this type of triage process where the working level official consults assessment tools at his or her disposal to determine whether a substantial risk of mistreatment exists.

Initial Case Triage Category 2: Informed by Country Assessment Rating

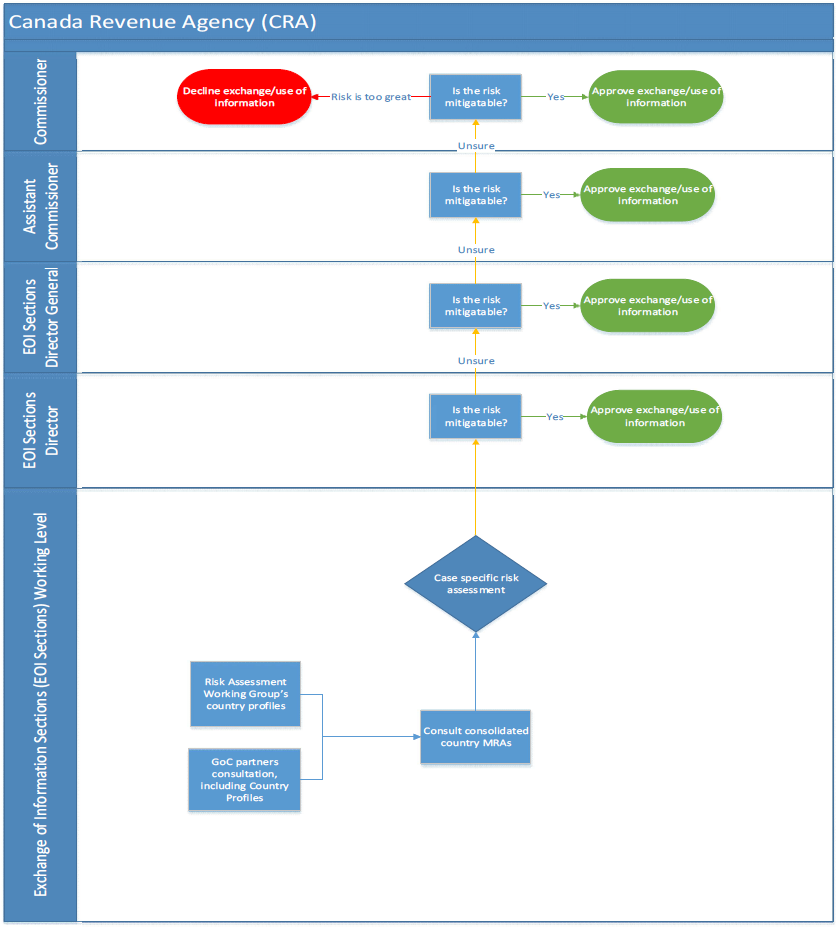

CSIS, CSE, FINTRAC, and RCMP require working level officials to use country assessment ratings that may trigger case escalation. For example, NSIRA has developed Figure 2 to illustrate this type of triage process where country assessment ratings may trigger case escalation.

Case Escalation

In addition to the two categories of case triage frameworks identified above, all departments except for FINTRAC, PS, CSE and TC make use of internal consultation groups/senior decision making committees when cases are identified as requiring consultation/escalation (e.g. working groups and senior management committee secretariats). The following table illustrates the various consultation groups across departments that would make determinations related to the ACA.

The general purpose of consultation groups is to serve as a single point of contact for employees who require assistance in assessing foreign information sharing activities or interpreting policy and procedure. Senior decision making committees are responsible for making determinations on the information exchange. They are the final decision making authority prior to escalation to the deputy head. NSIRA observed that leveraging the overall expertise of these groups may assist officials in consistently applying assessment criteria, as well as provide greater oversight for information exchanges with foreign entities.

Consistency in Implementation Across Departments

Beginning with the 2017 Ministerial Directions on Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities, it was required that departments maintain policies and procedures to assess the risks of information sharing relationships with foreign entities. While not specified in the Act or Directions, departments continue to implement country and entity assessments, a practice NSIRA has supported. NSIRA has previously raised concerns regarding the absence of unified and standardized approach to departments’ country assessments. The PCO-led community response to last year’s recommendation on this element stated in part that:

The information sharing activities of these organizations all serve either an intelligence, law enforcement, or administrative purpose with each carrying different risk profiles, privacy concerns, and legal authorities. Individual departments and agencies are responsible for establishing specific thresholds or triggers in their information sharing frameworks that are appropriate for their operational contexts. It is the view of the Government of Canada that applying the same threshold across all organizations for triggering, evaluating, and elevating cases is not necessarily practical nor essential to ensuring that each department or agency is operating in compliance with the Act.

In order to engage in the questions to which the divergence of thresholds gives rise, NSIRA asked departments to rank bi-lateral information exchanges with foreign partners in terms of volume, excluding exchanges with [***example of foreign entity information sharing***]. Nine of the twelve departments identified ███████ as a foreign exchange entity, a country which is widely recognized as having human rights concerns.

NSIRA then selected only those departments that initially utilize country assessment ratings as a triage method (i.e. FINTRAC, RCMP, CSIS and CSE). [***description of how departments determined foreign entity example***]. Nonetheless, in carrying out this analysis, NSIRA observed that all four departments relied on a combination of open source human rights reports and consultations with other departments. Additionally, RCMP, CSIS and CSE utilize classified intelligence sources.

However, although these departments utilize a similar approach when assessing a country, the assigned rating for ████ was not consistent. CSIS assigned █████████████; FINTRAC and RCMP assigned a [***description of department’s specific ratings***] ; and finally, CSE assigned a ██████ rating.

NISRA examined to what degree country ratings affected the level of approval required for an information exchange. Because CSE has assigned a rating of █████ when they receive a request from ████, a CSE official could require [***description of the factors used to determine the appropriate level process***] CSE acknowledged that its “human rights assessments do not necessarily correlate with the risk level assigned to an instance of sharing,” and nor do they “necessarily correlate to levels of approval or to restrictions to sharing.” [***description of the factors used to determine the appropriate level process***]

In contrast, according to their framework and methodology, an exchange with any one of the █████ authorities listed in the RCMP’s country and entity assessment list could result in an [***description of department’s specific ratings***] because █████ is associated with a country assessment rating. When an entity is yellow, the employee must consider whether or not there is a risk of mistreatment by looking at a list of criteria. If one or more of these criteria exist, the employee must send the case to a senior management committee. NSIRA observes that where the RCMP has a red country rating, the working level official must escalate to the senior management committee. Therefore, unlike CSE and CSIS, country ratings within the RCMP have direct impacts on approval levels.

NSIRA’s ACA report from last year recommended that departments should identify a means to establish unified and standardized country and entity risk assessment tools to support a consistent approach when interacting with Foreign Entities of concern. While PCO disagreed with this recommendation, NSIRA believes that there remain concerns regarding divergences in country and risk assessments.

NSIRA Finding #3: NSIRA found that even when departments employ similar methodologies and sources of information to inform their determination of whether or not a case involving the same country of concern should be scalated, significant divergences in the evaluation of risk and the required level of approval emerge.

Following this review, NSIRA intends to further scrutinize the processes employed regarding ACA triage and decision making by reviewing GAC and RCMP.

A case study as provided for in Box 1 exemplifies the divergent nature on the evaluation of risk where two departments’ considered responding to an identical request made by a foreign entity.

Box 1: A divergent decision-making process

[***description of the case study***] The foreign entity provided this information to GAC and CSIS and requested confirmation [***description of the information sharing request***]

In considering whether to respond to this request, GAC determined that the human rights record of the country in question generally and of the foreign entity specifically making the request were of significant concern. GAC’s senior decision making committee, working under the presumption that the individual’s detention was ongoing, considered whether the disclosure of this information “would not substantially increase the detainee’s risk of mistreatment.” The senior decision making committee determined that confirmation of the individual’s previous employment status with GAC was permissible, subject to the determination of CSIS’s assessment.

Ultimately, the decision by CSIS was made by a DG-level executive and, as the foreign entity was listed by CSIS as a restricted partner, information was not shared.

The assessment by GAC’s senior decision-making committee is of concern. The Act and the Directions impose that departments consider whether disclosing or requesting information “would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment.” [***legal advice to department***]

NSIRA agrees with this interpretation of the law, but not with its implementation by GAC in this case. GAC’s position was that responding to the request “would not aggravate” the risk of mistreatment. However, NSIRA is of a different view. Regardless of the information sought, the human rights record of the foreign entity and of the foreign country was of significant concern, and GAC was operating under the presumption that the individual may have already been subjected to mistreatment. While GAC’s sharing could not have accounted for any mistreatment that could have occurred earlier, responding to the request given the facts of this case would have nonetheless resulted in a substantial risk of mistreatment. Therefore, this case should have been refered to the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs for consideration.

NSIRA also observes that this case was triaged at different levels within GAC and CSIS. In GAC’s triage process, the decision was made at the higher senior decision-making committee that disclosure was permissible. Comparatively, CSIS’s decision-making process was completed prior to reaching their senior-level committee and yielded the opposite result. The different levels of decision-making and different outcomes underscore a problematic inconsistency in how each organization considers the same information to be disclosed to the same foreign entity. Furthermore, while a department responsible for the information may consult with other departments as to whether disclosure of information is permissible, it cannot abdicate this responsibility and decision-making to another department.

NSIRA Finding #4: NSIRA found a procedural gap of concern in a case study involving the disclosure of information, even though information was ultimately not shared. The risk of mistreatment was substantial and the decision should have been referred to the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs as the accountable deputy minister for this request.

Mitigation Measures

Use of Mitigation Measures

To decrease the risk of mistreatment, departments will employ mitigation measures such as caveats, assurances, sanitization, and redactions. The most common mitigation measures are caveats and assurances. Caveats are specific stipulations appended to information to limit or prohibit certain uses of information unless otherwise authorized by the issuing department. For example, any departments use a ‘third party’ caveat that restricts further dissemination of the information to other departments (domestic and foreign), unless the originating department is consulted on the request to share.

Assurances are not specific to a single information exchange; rather, these are agreements with foreign entities (whether formal or informal), which aim to help ensure that a particular foreign entity understands Canada’s position on human rights and that the entity, in turn, agrees to comply with this expected behaviour. For example, when formulating a risk mitigation strategy for an information exchange, departments will consider written or verbal assurances, who provided the assurance (i.e. working level official or agency head), and whether the assurance is considered credible and reliable.

Furthermore, CSIS, CSE, and GAC have highlighted a number of differences in the types of assurances sought, including a number of informal and formal methods. For example, verbal assurances, scheduled formal assurances, and ad-hoc written assurances can be sought by various levels.

In a related issue, NSIRA observed that there are [***description and an example of a Department’s ability to track compliance***] CSIS, GAC, and CSE indicated that there is ████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ is not specific to the ACA but is nonetheless key ████████████ when exchanging information with the Government of Canada.

Given that no cases were escalated to the level of deputy head, departments’ lower-level use of mitigation strategies would have taken on considerable prominence in decision making. In a subsequent review, NSIRA intends to further investigate policies of mitigation measures pertaining to their use and tracking.

CONCLUSION

This review assessed departments’ implementation of the directives received under the ACA and their operationalization of frameworks to address ACA requirements.

NSIRA’s first review of departments’ implementation of the Act and Directions was limited to a four month period (September-December 2019). As such, this review constitutes the first examination of the ACA over the course of one full year. NSIRA believes that it is now in a position to conduct in-depth case study assessments of individual departments’ adherence to the ACA and Directions, irrespective of whether or not a department reported any cases to its deputy head. Additionally, future reviews will follow up on the ongoing implementation of NSIRA’s past recommendations.

Annex A: Findings

NSIRA Finding #1: NSIRA found that CBSA and PS did not finalize their policy frameworks in support of Directions received under the ACA over the review period.

NSIRA Finding #2: NSIRA found that from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020, no cases under the ACA were escalated to deputy heads in any department.

NSIRA Finding #3: NSIRA found that even when departments employ similar methodologies and sources of information to inform their determination of whether or not a case involving the same country of concern should be escalated, significant divergences in the evaluation of risk and the required level of approval emerge.

NSIRA Finding #4: NSIRA found a procedural gap of concern in a case study involving the disclosure of information, even though information was ultimately not shared. The risk of mistreatment was substantial and the decision should have been referred to the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs as the accountable deputy minister for this request.

Annex B: Canada Border Services Agency

Framework updates: In 2018, Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) issued a high-level policy document in response to the 2017 MD. Since then, CBSA has drafted updated policies and procedures that have not yet been finalized.

Working Groups: CBSA Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment Working Group (ACMWG)

Senior Management Committee: Senior Management Risk Assessment Committee (SMRAC). This committee convenes on an as needed basis, to assess cases that have a potential for mistreatment.

[***description of CBSA’s decision making methodology***]

Country Assessment: In-house risk scoring template under development

Mitigation Measures: The CBSA is currently working to strengthen its formal framework/process for deciding whether substantial risk of mistreatment associated with a given request can be mitigated.

Annex C: Canada Revenue Agency

Framework Updates: The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) indicated that it did not make any changes to its framework since last year’s response. The department continues to refine its processes and has developed the Canada Revenue Agency Exchange of Information Procedures in the Context of Avoiding Complicity in the Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act.

[***departmental cabinet confidence***]

Working group: The CRA formed a Risk Assessment Working Group (RAWG) that developed a methodology to assess the human rights records of its information exchange partners, so that senior management can make informed assessments of the risk of mistreatment.

Canada has a large network of international partners with 94 tax treaties and 24 Tax Information Exchange Agreements. Canada is also a party to the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (MAAC), which includes 144 signatories. These International Legal Agreements allow the CRA to exchange information on request, spontaneously and automatically. Each legal agreement includes secrecy provisions (caveats) that govern appropriate use and disclosure. In addition, members of the Global Forum (Global Forum) on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes are subject to peer reviews on a cyclical basis, including on Confidentiality and Data Safeguard .

Senior Management Committee: During the review period a senior committee was not in place, however there was a formal process to escalate reviews/risk assessment through the Director, Director General and ultimately the Assistant Commissioner of the Compliance Programs Branch (CPB) who is accountable for the administration of the ACA.

Additionally, in July 2021, the CRA established an ACA governance framework that includes the ACA Panel, a senior management consultative committee to support risk assessments, reporting, recommendations, and priorities. The panel currently consists of DGs and Directors within the CPB and the Legislative Policy and Regulatory Affairs Branch. Also in July 2021, the CRA established an executive level committee to consider and develop recommendations on case specific engagements as well as issue identification and guidance. The committee consists of Directors across several directorates of the CRA that manage programs that are directly impacted by/reliant on exchange of information with other jurisdictions.

Triage: The initial assessment is done by a working level employee and requires, at minimum, director approval. The case may escalate to the DG and the AC and so on if there is doubt about risk mitigation.

In cases where risk was identified, there were challenges in conducting full assessments to determine if the risk was substantial, the CRA delayed disclosing the information until the full assessment could be completed. This was largely in part due to COVID-19. As such, files that normally would have been referred were temporarily put on hold and no action was taken during the review period.

The CRA informed NSIRA that funding from the November 2020 Fall Economic Statement was allocated to the creation of a dedicated risk assessment team. It is anticipated that the development and regular updating of country-level assessments and the preparation of individual-level risk assessments will transition to this new dedicated team housed within the CPB, in summer 2021.

The team will also be responsible for:

- Creating and formalizing the framework for consulting with CRA senior management and other government departments and agencies;

- Advising CRA officials who engage in exchange of information (EOI);

- Identifying mitigation and other factors specific to the type of information that CRA exchanges and that would impact risk assessment;

- Preparing annual and other reporting required under the Act and Directions;

- Providing awareness and training sessions; and

- Continuously improving documentation, policies, guidance, and procedures.

Country/Entity Assessments: Since January 2020, the CRA has completed their own set of mistreatment risk assessments for each potential information exchange, including the use of information received from the CRA’s information exchange partners in consultation with other Government of Canada partners. The CRA can only exchange information with another jurisdiction pursuant to a treaty, tax convention or other legal instrument that permits exchange of tax information.

The CRA uses a colour coded system to rate the risk related to a country: green; yellow; red. However, for specific or spontaneous exchanges of information, the CRA completes an analysis based on the specifics of the file to supplement the country specific risk assessment.

Mitigation Measures: Mitigation measures, including caveats (data safeguards and confidentiality provisions) are embedded in all legal instruments that govern and allow for all the CRA’s exchanges of information, while peer reviews of jurisdictions’ legal frameworks and administrative practices provide assurances of exchange partners’ compliance with international standards for exchange of tax information. According to CRA, all information exchanged during the review period were subject to these mitigation measures. Due to COVID19, and for the period under review, the CRA put on hold all exchanges where it was deemed there may be a residual potentially significant risk of mistreatment until a process and mitigation measures were in place, including to redact information. However, the CRA routinely redacted personal information where it would not impact the substance of the exchange for those mitigated risk exchanges that did proceed during this period.

Annex D: Communications Security Establishment

Framework Updates: No changes made to the framework in 2020. It is the same procedure as the last review period.

Working group: Based on the RFI, there are no working groups leveraged to assess the level of risk of mistreatment. The Mistreatment Risk Assessment Process follows a process that has been refined continuously since its inception in 2012. The higher the level of risk (low, medium, high, substantial), the higher approval authority required to exchange or use information.

Senior Management Committee: There is no Senior Management Committee. As explained above, CSE relies on an approval authority scale based on the level of risk (from low to substantial). Senior level officials are involved in the process when there are medium and high-risk cases, which require Director and Director General/Deputy Chief approval, respectively.

Triage: A CSE official performs an initial assessment by consulting the Mistreatment Risk Assessment (MRA), which considers equity concerns, geolocation and identity information, human rights assurances, risk of detention and a profile of the recipients’ human rights practices.

Low (For Low Risk Nations)

If the MRA indicates a low level of risk, the official will need Supervisor [***specific unit***], approval if they wish to proceed with the information exchange or use.

Low (For non-Low Risk Nations)

If the MRA indicates a low level of risk, the official will need Manager [***specific unit***], approval if they wish to proceed with the information exchange or use.

Medium

If the MRA indicates a medium level of risk, the official will need Director, Disclosure and Information Sharing approval if they wish to proceed with the information exchange or use.

High

If the MRA indicates a high level of risk, the official will need Director General, Policy Disclosure and Review or Deputy Chief, PolCom approval if they wish to proceed with the information exchange or use.

Substantial

If the MRA indicates a substantial level of risk, the official may not proceed with the information exchange or use.

Country Assessments: CSE establishes its own country assessments (which CSE refers to as Human Rights Assessments) by using information from OGDs, its own reporting, and open source information. Foreign entity arrangements are reviewed annually. These HRAs are part of CSE’s MRAs.

There are two types of MRAs: Annual and Case-by-case. Annual MRAs include foreign entities with whom CSE regularly exchanges information, [***description of the foreign entities with whom CSE exchanges information***] Caseby-case MRAs are conducted in response to particular requests. Case-by-case MRAs often concern individuals and information sharing activities. There are Abbreviated MRAs, which are a sub case-by-case MRA, and they are conducted for Limited Risk Nations. These nations are considered low risk by CSE.

When making MRAs, CSE does the following:

- assesses the purpose of the information sharing;

- verifies there are mistreatment risk management measures in existing information sharing arrangements;

- reviews CSE’s internal records on the foreign entity under consideration;

- consults other available Government of Canada assessments and reports related to the foreign entity;

- assesses the anticipated effectiveness of risk mitigation measures; and

- evaluates a foreign entity’s compliance with past assurances, based on available information.

CSE consults with GAC, DND, and the Ministers of Foreign Affairs and National Defence for some MRAs, usually case-by-case ones. CSE may also consult GAC for human rights-related advice in certain instances.

Mitigation Measures: CSE considers a number of mitigation factors, such as risk of detention, [***statement regarding information sharing obligations of partners***] caveats, formal assurances, and bilateral relationships. CSE’s principle mitigation measure is Second Party assurances. [***statement regarding information sharing obligations of partners***]

Identifying/Sensitizing: The DG, Policy Disclosure and Review or the DC PolCom review high-risk cases. 303 information-sharing requests were assessed for risk of mistreatment and 10 of them (3%) were referred to the Director, Disclosure & Information Sharing. For the 2020 review period, the Deputy Chief, Policy and Communications was responsible for ACA accountability and quality assurance.

Annex E: Canadian Security Intelligence Service

[***Info-graphic of CSIS’s Risk Assessment process***]

Framework Updates: While there were no changes during the 2020 review period, CSIS modified its procedure on January 2021. Most notably, cases will only be escalated to ISEC if the DG cannot determine if the substantial risk can be mitigated. In addition, CSIS merged the [***statement regarding internal process***] CSIS updated its human rights ‘Assurances’ procedures as a stand-alone policy. This policy requires CSIS Stations to seek assurances from [***statement regarding internal process***] coordination responsibilities for ISEC were moved to the ██████████. Through that, the █████ became ISEC’s Chair.

Triage: CSIS working-level officials do the initial assessment. This assessment requires the official to determine if one or more of the four risk criteria are met. These criteria are:

- “Based on the available information about the foreign entity, if the information is disclosed or requested, is there a probability that the foreign entity will engage in torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment against an individual(s)?”

- “If the information is disclosed or requested, is there a probability that the foreign entity will disseminate the information in an unauthorized manner to a 3rd party, which may result in torture or other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment against an individual(s) by that 3rd party?”

- “If the information is disclosed or requested, is there a probability that it may result in the extraordinary rendition of an individual(s) by the foreign entity which would lead to the individual(s) being tortured or subject to other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment?

- “If the information is disclosed or requested, is there a probability or an extrajudicial killing of an individual(s) by the foreign entity or other security entities within the country?”

Four scenarios could occur before a case lands at ISEC:

[***description of four possible scenarios and the assessment criteria used to determine risk mitigation and/or ecalation***]

Working Group: While there is a senior management committee, there is no working level group on the operations side.

Senior Management Committee: ISEC is CSIS’s senior-level review committee for foreign information sharing activities. It is composed of CSIS senior managers and representatives from DoJ and GAC. This committee is responsible to determine if a case poses a substantial risk and if it can be mitigated. If ISEC cannot determine if the substantial risk is mitigatable, the case is referred to the Director. Of note, GAC and DoJ are no longer voting members on ISEC but will continue to provide feedback and advice.

Country Assessments: CSIS conducts its own country assessments. Each information exchange arrangement with a foreign entity has its own Arrangement Profile (AP). APs include a summary of the human rights summary.

Mitigation Measures: CSIS relies on a few mitigation measures. First, CSIS widely uses ‘Form of Words’, which include caveats. Second, CSIS uses assurances and relies on standardized templates provided to foreign entities. CSIS may also tailor assurances to address specific concerns, such as extra-judicial killings.

Identifying/Sensitizing Information: ██████ is responsible for CSIS’s information sharing framework. [***name of a specific unit***] is responsible for official policy management. Concerned program areas are responsible for applying related polices and procedures for ACA-related activities.

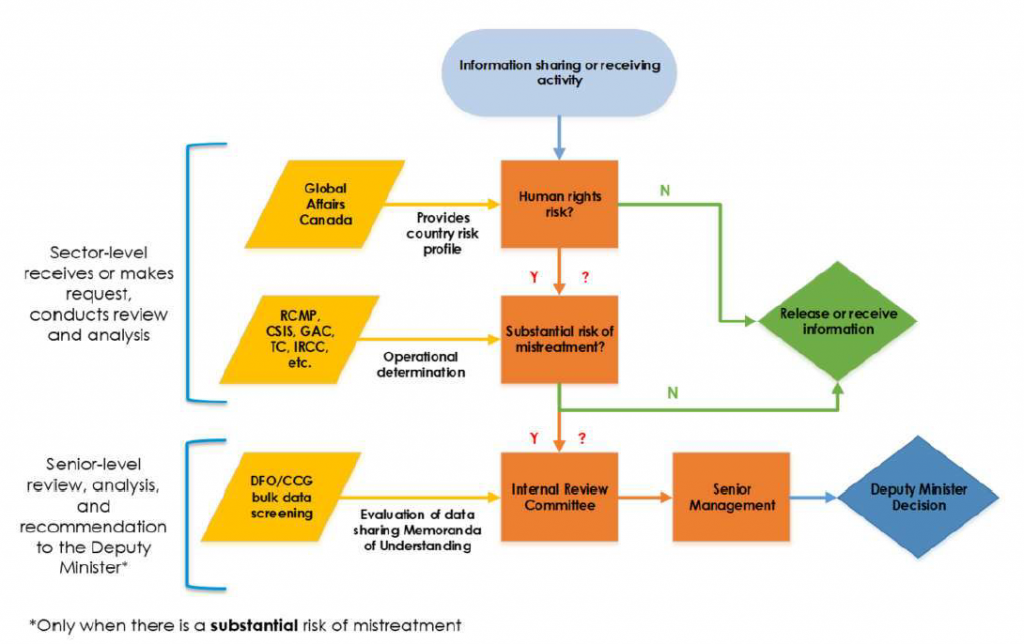

Annex F: DFO

Framework Updates: Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) did not make any changes to last year’s approach.

Triage: The initial assessment is made by the person receiving the request for information sharing or who first comes into possession of information derived from a foreign source. Risk is determined on a case-by-case basis.

The sector-level analyst/officer does the initial assessment and relies on OGD assessments to determine the level of risk. They determine the level of risk in relation to the specific case and whether they assess that there is a substantial risk or not will impact the level of approval. If the analyst/officer does not think there is risk, the case may proceed. This, according to the decision screen and information received, does not require any manager or senior level approval.

If the analyst/officer believes or is unsure that there is a substantial risk, the senior-level Internal Review Committee (IRC) must seek DM approval.

Working Group: Internal Review Committee

Senior Management Committee: DFO employs the use of a decision screen and the IRC as demonstrated above. It is unclear whether DFO has developed guidance to help officials and management accurately and consistently determine the risk of mistreatment.

Country Assessments: DFO relies on country assessments conducted by GAC (as well as DFO legal services, RCMP and CSIS as needed) to make mistreatment risk determinations.

Mitigation measures: DFO indicated that it employs the use of caveats and assurances as necessary but has not yet had to seek such assurances. As such, there is no tracking mechanism in place. The Department is able to retroactively determine when, how, and why a decision was made through its record keeping system. A process is in place to record the details of each case, its evaluation process, and any resulting actions and decisions.

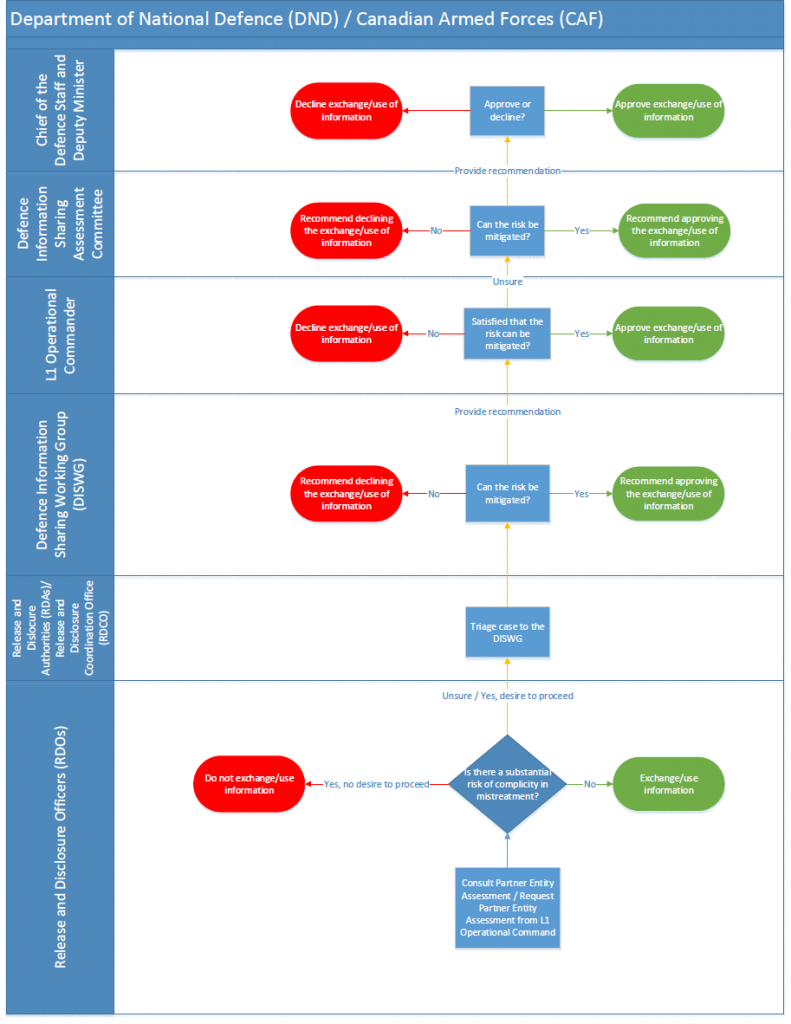

Annex G: Department of National Defence/Canadian Armed Forces

Framework Updates: The Department of National Defence (DND) indicated that there were no changes to its framework since last year’s response.

Triage: The process of assessing risk is largely the same across all three forms of information sharing transactions. The process involves examining country human rights conditions, and researching specific partner entities, including any reports of mistreatment. Adverse information on a foreign partner is reviewed by the Defence Information Sharing Working Group (DISWG) and recommendations are made to the implicated L1s on how to manage information sharing activities (request, disclosure, or use). There are no differences in the types of mitigation measures employed across the three forms of information sharing. The primary governance document Release and Disclosure Officers (RDOs) and Release and Disclosure Authorities (RDAs) must adhere to is the CDI Interim Functional Directive: Information Sharing with Certain Foreign States and their Entities.

Working Group: The Defence Information Sharing Working Group (DISWG) is a working-level committee led by the Release and Disclosure Coordination Office (RDCO) within CFINTCOM that serves as an advisory body to operation Commanders regarding issues covered under the ACA. This Working Group exists as a platform for open dialogue related to information sharing arrangements and transactions. This group convenes monthly, or as required.

Senior Management Committee: The Defence Information Sharing Assessment Committee (DISAC) is chaired by the Chief of Defence Intelligence / Commander CFINTCOM . The DISAC’s primary object is to act as an advisory committee for the Deputy Minister and the Chief of Defence Staff in support of their decision making regarding issues pertaining to the ACA.

Country Assessments: Currently, RDCO has established a list of low-risk countries that can be referred to by other L1s. Inclusion in this list indicates CDI’s confidence that sharing information with government entities of that foreign state can take place without a substantial risk of mistreatment. Moreover, RDCO has developed a draft methodology for Country Human Rights Profiles to classify countries as low, medium, or high risk but has only begun producing country human rights profiles on a few medium and high-risk countries and the methodology has not yet formally approved. These profiles will be used by other L1s in the development of specific Partner Entity Assessments and to inform the overall risk assessment of sharing information with foreign entities.

Information Management: There is no common shared system or repository for all RDOs. Information decisions are recorded by RDOs at the unit level. In some cases, all transactions are recorded using a spreadsheet and should include all details relating to the collection, retention, dissemination or destruction of the information, but the precise format will vary. CFINTCOM is working to standardize RDO logs across DND/CAF. From an information management perspective, there have been no changes since last year’s report. Records of discussion of all DISWG meetings are kept centrally within RDCO/CFINTCOM and it is possible to retroactively determine how and why a decision or recommendation was made.

Mitigation Measures: DND uses mitigation measures to reduce the risk of mistreatment. For example, DND uses measures such as the sanitization of information, the inclusion of caveats, and/or the seeking of assurances, including on low-risk cases in order to err on the side of caution.

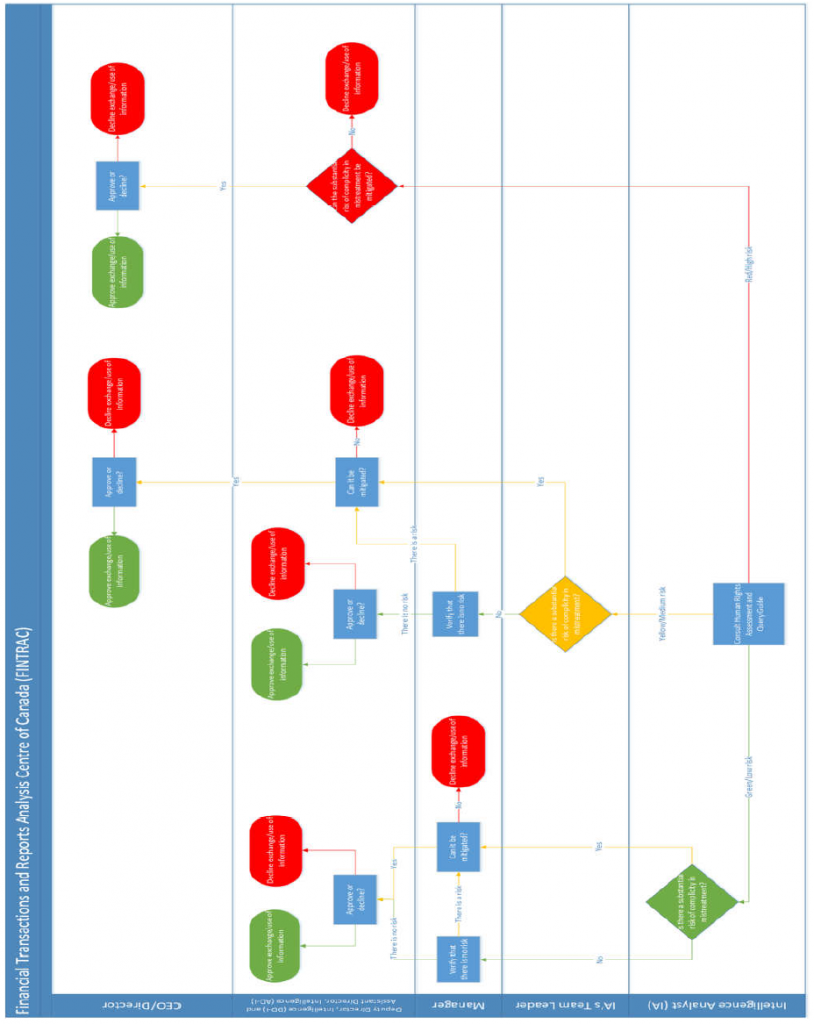

Annex H: FINTRAC

Framework Updates: The Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) did not make any changes to their framework for the 2020 review year.

Triage: Who does the initial assessment will depend on the risk level classification of the country. If it’s green, the intelligence analyst (IA) does the risk assessment. If it’s yellow, the IA’s team leader does the risk assessment. If it’s red, Senior Level does the risk assessment. Regardless of the determined risk level, Senior Level must ultimately approve or decline the information exchange/use.

Partnerships and Working Groups: FINTRAC makes use of external organizations, such as the Egmont group, to ensure that member organizations are adhering to global standards against mistreatment. If one of these groups is found to have breached their duty of care, and is expelled from the group, then FINTRAC will cease to exchange information until the matter has been rectified. FINTRAC enters Memoranda of Understandings (MOUs) with nations who wish to exchange information with them. To do so, each nation is assessed using a variety of criteria to determine their risk rating and whether an MOU should be established.

FINTRAC also regularly participates in ISCG meetings alongside other departments.

Senior Management Committee: FINTRAC does not have a senior management committee to determine risk like other departments. Instead, they rely on senior management and the Director to make final decisions on cases.

Country Assessments: FINTRAC established its own country assessments. Establishing each country assessment involves gathering pertinent information on the human rights situation in the country and using indicators to assess the risk level of mistreatment of each country. During the development of the country assessment process, FINTRAC consulted with other agencies/government departments captured under the ACA.

The Manager of International Relationships is responsible for monitoring and assessing the human rights profile of countries with which FINTRAC shares an MOU.

Mitigation Measures: Caveats and assurances are established at the signing of an MOU and repeated whenever sharing information with any foreign entity. The sharing of information is not allowed without a signed MOU.

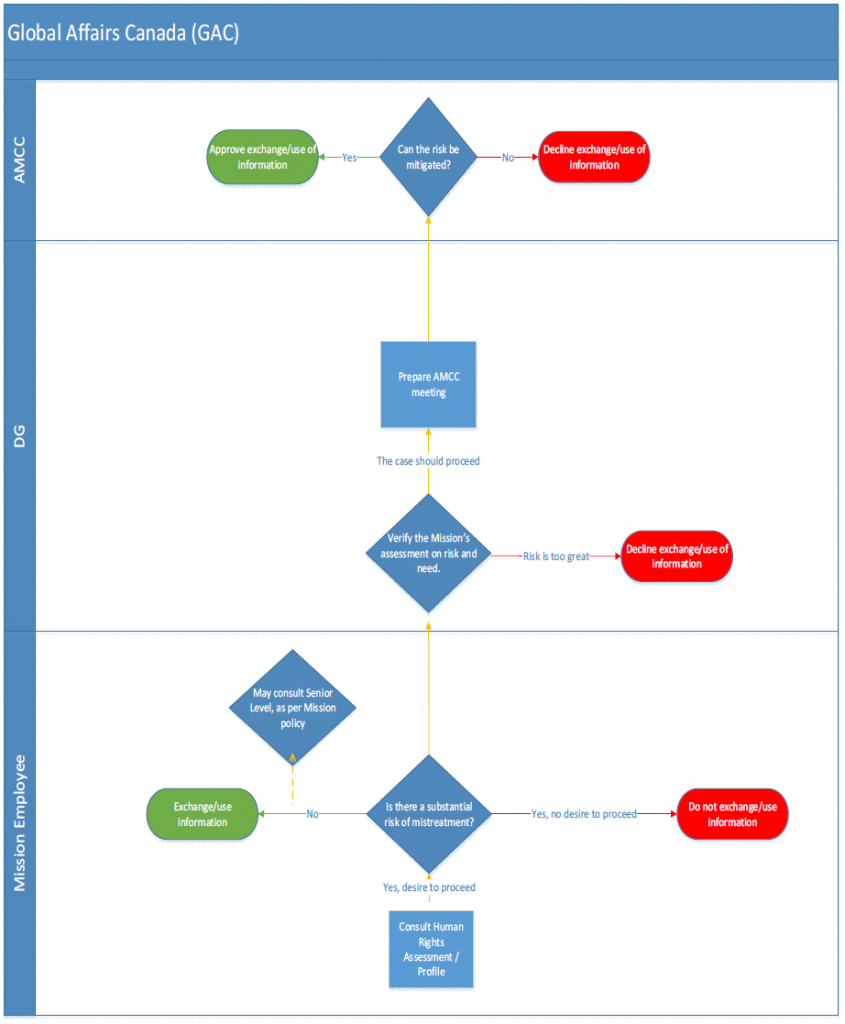

Annex I: Global Affairs Canada

Framework Updates: Global Affairs Canada (GAC) indicated that no changes to their framework was made during the current review period.

Triage: There is not one unified set of processes at GAC for determining whether information being used by the department is likely to have been obtained through the mistreatment of an individual by a foreign entity. If an official determines that information that he or she has received is likely to have been obtained through the mistreatment of an individual by a foreign entity and that official still wants to use the information, they are instructed in their training to consult with their Program management at HQ. Should that manager be unable to make a determination on their own as to whether the use would comply with the Act, they will consult the relevant departmental policy group and the department’s Legal Services Unit.

Working Groups: The Ministerial Direction Compliance Committee Secretariat

Senior Management Committees: The Ministerial Direction Compliance Committee (MDCC) meetings focuses on the following:

- Has the information, the use of which is being sought, likely been derived from mistreatment?

- What are the proposed measures to mitigate the risks? What is the likelihood of their success?

- Consider the justifications for and proportionality of any potential involvement with the foreign state or entity that may result in mistreatment.

The MDCC Secretariat will create a record of decision and circulate it for comment by MDCC members. Once finalized, it will be kept by the Secretariat for future reporting. The MDCC Secretariat follows up with the requesting official for updates on the outcome of the situation and requests a final update from the requesting official once the situation is resolved. Currently the MDCC Secretariat consists of one person.

Country Assessments: Global Affairs Canada’s human rights reports provide an evidence-based overview of the human rights situation in a particular country, including significant human rights-related events, trends and developments and include a section focused on mistreatment. There are no scores for countries however, and it is up to the officials to assess the risk based on the information in the reports.

Mitigation Measures: The Legal Services Unit and/or Intelligence Policy and Programs division will provide guidance on the limitations and the prohibitions of the use of information obtained through mistreatment. They are also able to propose potential mitigation measures, such as sanitization of the information, if there is a risk of further mistreatment; of depriving someone of their rights or freedoms; or if the information could be used as evidence in any judicial, administrative or other proceeding.

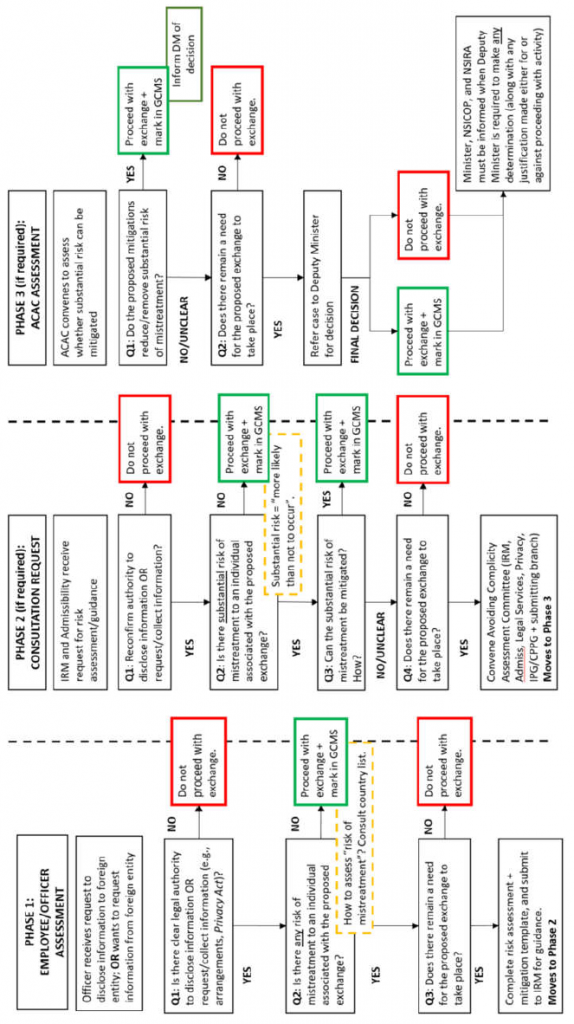

Annex J: IRCC

Framework Updates: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) indicated that there were no changes to its procedures regarding the disclosure of information to foreign entities.

Triage: The initial assessment is done by the employee/officer receiving a request to disclose information. Officers are provided with a country assessment tool that provides a country-level risk assessment. If the country is listed as low-risk and the employee does not believe there are any risks of mistreatment, they may proceed with the exchange and record the details of that exchange (i.e., what information was exchanged; to which country, etc) into the Global Case Management System (GCMS). If the country is high-risk, or the officer believes that there is any risk of mistreatment and they wish to pursue with the case, then the officer is required to refer the case to IRM and Admissibility to assess the risk of the exchange.

Senior Management Committee: IRCC has the Avoiding Complicity Assessment Committee. The Committee is comprised of executives representing relevant policy, operations, legal and privacy branches within the Department. The purpose of the Committee is to reassess whether the circumstances of the case meet the “substantial risk” threshold, and to determine whether mitigations could be sufficiently imposed to allow for the disclosure. If the Committee is unable to unanimously determine if the risk can be mitigated, and there remains a need to disclose the information to the requesting foreign entity, then the case will be referred to the Deputy Minister for final decision.

Country Assessments: IRCC officers are instructed to refer to an initial country assessment tool when they are contemplating any disclosure or request for information from a foreign entity. This tool provides a general assessment of the country’s risk. If the country is identified as a high-risk country, then the officer is required to make a Consultation Request before disclosing, requesting or using information. If the country is identified as medium-risk, then it is recommended that the officer make a Consultation Request.

Mitigation Measures: Possible mitigation measures for a case where a substantial risk of mistreatment has been determined, if available, would be established in the Consultation Request assessment and, if necessary, in the Avoiding Complicity Assessment Committee’s recommendation. In either case, the mitigations will be manually recorded in the case file where they can be later recalled and noted in the Annual Report.

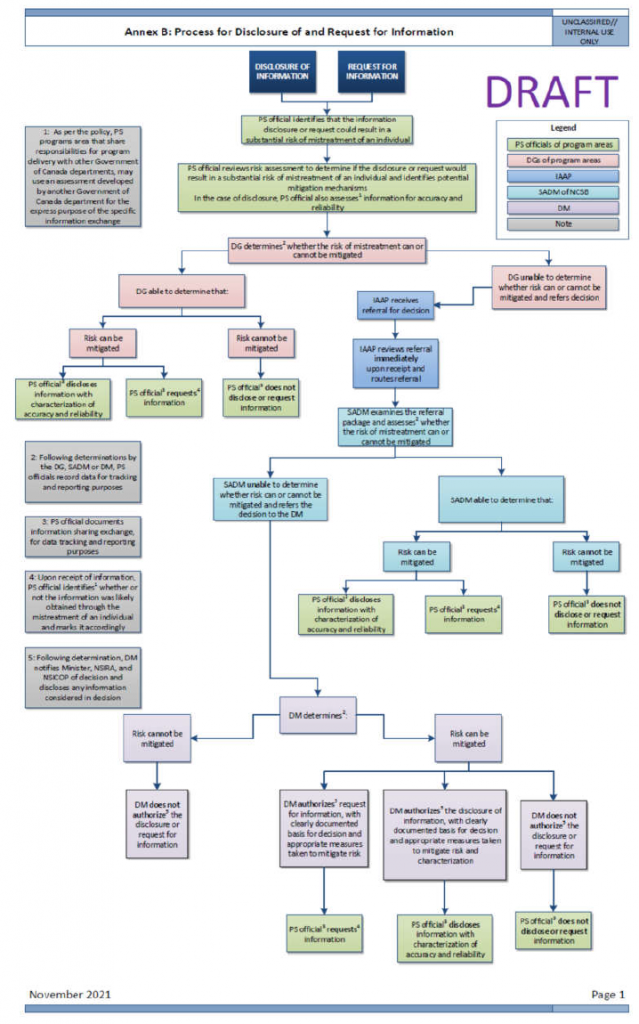

Annex K: Public Safety

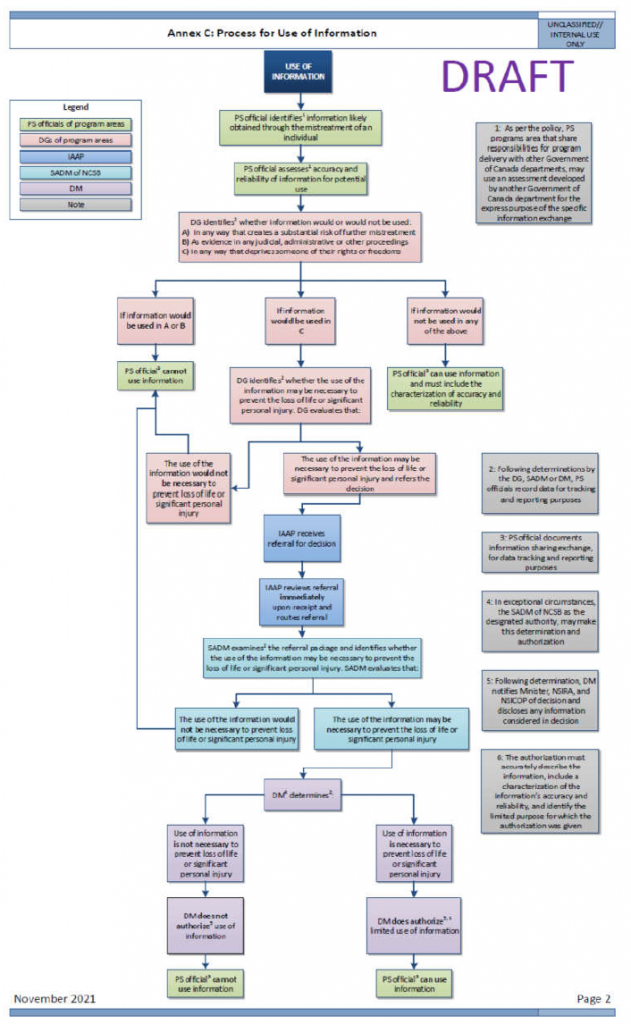

Please note that the above flow charts are draft and have not yet been approved.

Framework Updates: Public Safety (PS) does not yet have a framework for deciding whether an exchange of information with a foreign entity would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual. PS noted, however, that it has drafted a departmental policy to support the department’s implementation of the Directions but it has not yet been approved by senior management.

Triage: PS officials at the operational level are responsible for identifying whether the disclosure of or request for information would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual. Prior to the disclosure of or request for information to/from a foreign entity, PS officials, as per the draft policy, are expected to:

- review risk assessments and information sharing arrangements/agreements to determine risks;

- identify mitigation measures as needed; and

- seek DG approval for the disclosure or request; and the DG would determine whether the risk can or cannot be mitigated and whether the case should be referred to the DM for determination and decision.

- PS officials at the operational level are responsible for identifying whether information for potential use was likely obtained through the mistreatment of an individual. As per the draft policy, prior to the use of information, PS officials are expected to:

- conduct an assessment to determine if the information was likely obtained through the mistreatment of an individual, if not previously completed by PS officials or another government department, and mark it accordingly, based on DG-level determination;

- assess and characterize the accuracy and reliability of the information; and,

- advise their DG of the circumstance; and the DG would determine whether the information would be used as per section 3 of the Directions and refer the decision to the DM to determine if the use of information in any way that deprives someone their rights or freedoms is necessary to prevent the loss of life or significant personal injury.

For PS program areas where responsibilities for program delivery are shared among multiple Government of Canada departments, PS officials may use accuracy and reliability assessments conducted by another Government of Canada department for the express purpose of the specific information exchange. In these cases, and where PS does not have sufficient information (such as the source of the information) to conduct an assessment, it will require Government of Canada departments to attest to having conducted the assessment. This same principle applies risk assessments and assessments as to whether information was likely obtained through the mistreatment of an individual.

Working Group: The ISCG is the primary interdepartmental forum for supporting interdepartmental collaboration and information-sharing between members as they implement the Act and Directions and is regularly attended by all members.

PS participates in the ISCG in three ways as the:

- chair, coordinator and PS policy lead;

- area responsible for implementing the ACA;

- legal counsel representative.

PS has also made progress with ISCG guidance. However, due to COVID-19, the ISCG was limited in its capacity to convene meetings.

Senior Management Committee: PS does not have a formal senior management committee to review high-risk cases. The Investigative Authorities and Accountability Policy (IAAP) unit supports program areas in the referral process to the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister (SADM) of the National and Cyber Security Branch for further examination. Acting as a senior Public Safety official, the SADM is responsible for referring cases to the Deputy Minister if they are unable to determine whether the risk of mistreatment can be mitigated.

Country Assessments: PS currently does not have any country assessments completed and plans to use other department’s assessments, but as outlined in its draft policy, PS expects to conduct country and entity assessments as part of its annual risk assessment process. The risk assessment process will ensure that an agreement with the foreign entity is in place prior to information sharing exchanges; review risk and country assessments developed by portfolio agencies (e.g. CSIS) and other departments (e.g. GAC), and consider human rights reporting from non-government entities.

The IAAP will coordinate, on an annual basis, risk assessments. To do so, IAAP may, for example, review human rights reports developed by Global Affairs Canada (GAC), country assessments prepared by portfolio agencies (e.g. CSIS), human rights reporting from non-government entities and country/entity specific material.

Mitigation Measures: PS currently has developed a draft policy to address mitigation measures and caveats. The draft policy will provide guidance to officials on how to assess risk and apply mitigation measure, while also defining approval levels and country assessment responsibilities.

Once a risk of mistreatment has been identified, the PS official is required to undertake a risk mitigation assessment prior to requesting the information. Approved risk mitigation mechanisms include:

- the caveating of information,

- obtaining assurance and/or

- disclosing a limited amount of the information.

The policy also outlines requirements regarding the use of congruent mitigation mechanisms to collectively reduce the risk.

Annex L: Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Framework Updates: There were no changes to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s (RCMP) framework in 2020. RCMP has undertaken a number of internal reviews of its information sharing framework and continues to refine and optimize its processes.

RCMP also noted that it was in its final stages of rolling out an online training course specifically tailored to the ACA.

Triage: The Foreign Information Risk Advisory Committee (FIRAC) process may be initiated if and when an information exchange involves a country identified as high or medium risk. A low-risk case would only be sent if an official believes there is the potential for mistreatment.

All RCMP personnel are required to consider the risk of mistreatment before requesting, disclosing or using information and to engage the FIRAC process if there is a substantial risk identified to a specific individual(s) with a country of exchange.

An employee is almost always the one to perform the initial risk assessment. When an entity is green, the employee may exchange or use information without consulting FIRAC, unless they express doubts. When an entity is yellow, the employee must consider whether or not there is a substantial risk of mistreatment by looking at a list of criteria (similar to CSIS). If one or more of these criteria is present, the employee must send the case to FIRAC. If the entity is red, the employee must send the case to FIRAC for the initial assessment, unless no personal information is exchanged.

Working Group: Law Enforcement Assessment Group (LEAG). Full-length LEAG assessments include classified information from other Federal departments and agencies. The FIRAC Portal was developed to allow RCMP employees to access the assessments, and to further support compliance with the directions.

Senior Management Committee: FIRAC was established to facilitate the systematic and consistent review of RCMP files to ensure information exchanges do not involve or result in the mistreatment of any person.

FIRAC holds the responsibility to determine if a substantial risk exists and in cases where a substantial risk of mistreatment exists, make a recommendation on whether the proposed mitigating measures are adequate to mitigate the risk.

FIRAC’s recommendations are made by the Chair, upon the advice of the Committee, to the appropriate Assistant Commissioner / Executive Director responsible for the operational area seeking to disclose, request or use the information.

FIRAC determines if the risk is mitigatable or not. If it is, the case goes to the Assistant Commissioner. If it is not, FIRAC declines the exchange or use of information.

Country Assessments: An in-house country assessment model has been completed.

Countries are listed in alphabetical order, along with any specific foreign entities (i.e. police forces, military units, etc.) that have been assessed. For each entity, the risk level (Red-High, Yellow-Medium, Green-Low) is provided, as are the specific crime types and conditions.

Mitigation Measures: The RCMP leverages existing MOU’s with specific partners to partially mitigate underlying risk, in particular where mutually agreed standards around human rights exist as well as having a good track record for respecting caveats. Similarly, officials work with Liaison Officers to identify any relevant assurances or strategies, factors or conditions that could mitigate the risk of mistreatment posed by the information exchange, request for information or use of information.

All mitigation measures used are tracked through the FIRAC by filling in a FIRAC Request Form. Noting which mitigations/caveats are used is a mandatory part of the process.

Annex M: Transport Canada

Does not have a departmental framework for assessing ACA considerations, outside of the Passenger Protect Program (PPP).

Changes: Transport Canada (TC) developed a corporate policy in September 2020 to highlight the department’s ACA-related requirements, roles and responsibilities and remains a participant in PS framework.

Triage: Relies on PS’ framework for the Passenger Protect Program.

Should they have any concerns about a request for information from a foreign partner they will consult with other agencies, such as CSIS or GAC.

Working Group: TC is a voting member of the PPP Advisory Group but does not have any responsibility for drafting case briefs. At each meeting of the PPP Advisory Group, TC has ensured that all other voting members have acknowledged TC’s SATA-legislated responsibility for sharing the List with domestic and foreign air carriers, and its associated responsibilities under the ACA.

Senior Management Committee: TC does not have any senior management committee in place to further review cases with a potential for mistreatment.

Country Assessments: Rely on other government departments.TC relies on assessments by other departments such as PS and GAC.

Mitigation measures: The framework was established by Public Safety (lead on PPP), with consultations with the PPP partners (RCMP, CSIS, CBSA). TC has worked with PS to integrate mitigation measures into the operating procedures and protocols of PPP partners.