Form Testing

- Date Modified:

Date of Publishing:

| Abbreviation | Expansion |

|---|---|

| 2017 MD | 2017 Ministerial Direction on Avoiding Mistreatment by Foreign Entities |

| ACA (ACMFEA, or “the Act”) | Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act |

| ADM | Assistant Deputy Minister |

| AMCC | Avoiding Mistreatment Compliance Committee |

| CBSA | Canada Border Services Agency |

| CRA | Canada Revenue Agency |

| CRCC | Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP |

| CSE | Communications Security Establishment |

| CSIS | Canadian Security Intelligence Service |

| DFO | Department of Fisheries and Oceans |

| DND/CAF | Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces |

| EPPP | Enhanced Passenger Protect Program |

| FINTRAC | Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada |

| FIRAC | Foreign Information Risk Advisory Committee |

| FPNS | Federal Policing National Security |

| GAC | Global Affairs Canada |

| GATE | Governance, Accreditation, Technical Security and Espionage |

| HOM | Head of Mission (or Chargé) |

| HRR | Human Right Report |

| ICCPR | International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights |

| ICE | Integrated Collaborative Environment |

| INPL | Intelligence Policy and Programs Division |

| IRCC | Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada |

| ISCG | Information Sharing Coordination Group |

| LEAG | Law Enforcement Assessment Group |

| LO | Liaison Officer |

| MDCC | Ministerial Direction Compliance Committee |

| NSICOP | National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians |

| NSIRA | National Security Intelligence Review Agency |

| OiC | Orders in Council |

| PPP | Passenger Protect Program |

| PS | Public Safety Canada |

| RCMP | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| RFI | Requests for Information |

| TC | Transport Canada |

| Abréviation | Développement |

|---|---|

| AL | Agent de liaison |

| AMC | Affaires mondiales Canada |

| ARC | Agence du revenu du Canada |

| ASFC | Agence des services frontaliers du Canada |

| CANAFE | Centre d’analyse des opérations et déclarations financières du Canada |

| CCDM | Comité de conformité à la directive ministérielle |

| CCEMT | Comité de conformité pour éviter les mauvais traitement |

| CCETP | Commission civile d’examen et de traitement des plaintes relatives à la GRC |

| CCRIE | Comité consultatif sur les risques – Information de l’étranger |

| CDM | Chef de mission (ou chargé de mission) |

| CPSNR | Comité des parlementaires sur la sécurité nationale et le renseignement |

| CST | Centre de la sécurité des télécommunications |

| DC | Décret en conseil |

| DI | Demande d’information |

| ECI | Environnement collaboratif intégré |

| GASE | Gouvernance, accréditation, sécurité technique et espionnage |

| GCER | Groupe de coordination d’échange de renseignements |

| GEAL | Groupe d’évaluation de l’application de la loi |

| GRC | Gendarmerie royale du Canada |

| IM-2017 | Instructions du ministre de 2017 visant à éviter la complicité dans les cas de mauvais traitements par des entités étrangères |

| INPL | Direction des politiques et des programmes liés au renseignement |

| IRCC | Immigration, Réfugiés et Citoyenneté Canada |

| Loi visant à éviter la complicité, la Loi | Loi visant à éviter la complicité dans les cas de mauvais traitements infligés par des entités étrangères |

| MDN/FAC | Ministère de la Défense nationale/Forces armées canadiennes |

| MPO | Ministère des Pêches et des Océans |

| OSSNR | Office de surveillance des activités en matière de sécurité nationale et de renseignement |

| PIDCP | Pacte international relatif aux droits civils et politiques |

| PPP | Programme de protection des passagers |

| PPP-A | Programme de protection des passagers amélioré |

| RDP | Rapport sur les droits de la personne |

| SCRS | Service canadien du renseignement de sécurité |

| SMA | Sous-ministre adjoint |

| SNPF | Sécurité nationale et Police fédérale |

| SP | Sécurité publique Canada |

| TC | Transports Canada |

This review focuses on departmental implementation of directions received through the Orders in Council (OiC) issued pursuant to the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACMFEA, ACA, or “the Act”). This is NSIRA’s third annual assessment of the statutorily mandated implementation of the directions issued under the ACA.

This year’s review covers the 2021 calendar year and has been split into three sections. First, the review addresses the statutory obligations of all departments. Sections two and three of the review focus on in-depth analysis of how the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Global Affairs Canada (GAC) have implemented the directions under the ACA. NSIRA has used case studies, where possible, to examine these departments’ implementation of the ACA framework.

NSIRA has observed that this is the third consecutive year where there have been no cases referred to the deputy head level in any department. This is a requirement of the OiC in cases where officials are unable to determine if the substantial risk can be mitigated. Future reviews will be attuned to the issue of case escalation and departmental processes for decision-making.

In the 2019 NSIRA Review of Departmental Frameworks for Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities (2019-06), NSIRA recommended that “the definition of substantial risk should be codified in law or public direction.” NSIRA notes that some departments have accounted for this gap by relying on the definition of substantial risk in the 2017 MDs. In light of the pending statutorily mandated review of The National Security Act, 2017 (Bill C-59) and the centrality of the concept of substantial risk to the regime governing the ACA, NSIRA reiterates its 2019 recommendation that the definition of substantial risk be codified in law.

In last year’s review NSIRA identified Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and Public Safety Canada (PS) as not yet having finalized their ACA policies. While CBSA and PS continue to make advancements these departments still have not fully implemented an ACA framework and supporting policies and procedures.

RCMP has a robust framework in place for the triage and processing of cases pertaining to the ACA. The in-depth analysis portion of this review found that the RCMP does not have a centralized system of documenting assurances and does not regularly monitor and update the assessment of the reliability of assurances. NSIRA also found that the RCMP has not developed mechanisms to update country and entity profiles in a timely manner, and the information collected through the Liaison Officer in the course of an operation is not centrally documented such that it can inform future assessments.

In the analysis of one of the RCMP’s Foreign Information Risk Advisory Committee (FIRAC) case files, NSIRA found that the Assistant Commissioner’s rationale for rejecting FIRAC’s advice did not adequately address concerns consistent with the provisions of the Orders in Council. In particular, NSIRA finds that the Assistant Commissioner erroneously considered the importance of the potential future strategic relationship with a foreign entity in the assessment of potential risk of mistreatment of the individual.

NSIRA conducted a review of all twelve departments by examining relevant policy and legal frameworks as communicated by the departments. The RCMP was responsive to NSIRA’s requests, providing documents and briefings within agreed time frames. Due to timing constraints, NSIRA relied heavily on the written record as provided. GAC demonstrated a willingness to provide NSIRA with the information requested, and made every effort to clarify requests. GAC was timely in their responses and provided access to people and information as requested.

NSIRA found that GAC is now strongly dependent on operational staff and Heads of Mission for decision-making and accountability under the ACA. This is a marked change from the findings of the 2019 review that found decision-making was done at the Ministerial Direction Compliance Committee (MDCC) at Headquarters.

GAC has also not conducted an internal mapping exercise to determine which business lines are most likely to be implicated by the ACA. Considering the low number of cases this year and the size of GAC, and that ACA training is not mandatory for staff, NSIRA has concerns that not all areas involved in information sharing within GAC are being properly informed of their ACA obligations.

NSIRA also notes that GAC has no formalized tracking, or documentation mechanism for the follow-up of caveats and assurances. This is problematic as mission staff are rotational and may therefore have no visibility as to their ability to rely on caveats and assurances based on past information sharing instances.

During the review, GAC demonstrated a willingness to provide NSIRA with the information requested, and made every effort to clarify requests. GAC has provided NSIRA with all documents requested within a reasonable time frame.

This review assessed departments’ implementation of the directives received under the ACA and their operationalization of frameworks to address ACA requirements. As such, this review constitutes the first in-depth examination of the ACA within individual departments.

This review is being conducted under the authority of paragraph 8(2.2) of the National Security Intelligence Review Agency Act (NSIRA Act), which requires National Security Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) to review, each calendar year, the implementation of all directions issued under the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACMFEA, ACA, or “the Act”).

This review will focus on departmental implementation of directions received through the Orders in Council issued pursuant to the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act. The overarching objective of this review is to assess whether departments are meeting their obligations under the ACA and associated directions. NSIRA is mandated to conduct this review on an annual basis.

Many departments and agencies in the Government of Canada routinely share information with foreign entities. Given that information sharing with entities in certain countries can result in a risk of mistreatment of individuals, it is incumbent upon the Government of Canada to evaluate and mitigate the risks that such sharing creates. This is particularly the case for information sharing related to national security and intelligence, where information often relates to alleged participation in terrorism or other criminal activity.

The 2017 Ministerial Direction on Avoiding Mistreatment by Foreign Entities (2017 MD), defined the substantial risk of mistreatment as:

[A] personal, present and foreseeable risk of mistreatment. In order to be ‘substantial’, the risk must be real and must be based on something more than mere theory or speculation. In most cases, the test for substantial risk of mistreatment will be satisfied when it is more likely than not that there will be mistreatment; however, in some cases particularly where there is a risk of severe harm, the ‘substantial risk’ standard may be satisfied at a lower level of probability.

This review will be NSIRA’s third annual assessment of the implementation of the directions issued under the ACA. This review will build on the previous reviews conducted in respect of avoiding complicity in mistreatment. The first review was in respect to the 2017 MD. The second review assessed the directions issued under the ACA, but was limited to the four months from when the directions were issued to the end of the 2019 calendar year. The third review was NSIRA’s first full year assessment of the implementation of the directions issued under the ACA for the 2020 calendar year.

NSIRA has focused on conducting in-depth reviews of how departments implement the directions under the ACA. This approach builds on the foundational knowledge obtained over the last three years and reviews how departments operationalize the directions under the ACA by using case studies to assess departments ACA frameworks in practice.

The review, covering the 2021 calendar year has been split into three sections. The first section addresses NSIRA’s statutory obligations covering a full year review of all departments. This year NSIRA conducted an in-depth review of two departments: the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Global Affairs Canada (GAC), sections two and three respectively.

Subsection 7(1) of the ACA imposes a statutory obligation on the deputy head to whom directions were issued to submit a report to the Minister regarding the implementation of those directions during the previous calendar year and publish a public copy of the report. The Minister must then provide the classified copy to NSIRA.

The obligations for departments noted above are mirrored in the NSIRA Act. Under subsection 8(2.2) of the NSIRA Act, NSIRA must, each calendar year, review the implementation of all directions issued under the ACA. Additionally, NSIRA has the statutory right to review the implementation beyond the specific requirements of the ACA, namely through its mandate to review any activity carried out by a department that relates to national security or intelligence.

The issued Orders in Council (OiC) include a reporting requirement, whereby decisions necessitating referral to the deputy head for determination must be reported to the Minister and subsequently the review bodies. This requirement creates additional accountability for decisions undertaken by departments and allows NSIRA to be informed of any potential issues outside of the annual reporting cycle.

This review encompasses the implementation of the directions for the 12 departments that were in receipt of the OiC pursuant to the ACA. The review period is January 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021. Additionally, NSIRA has selected two departments for more in-depth case study review: GAC and the RCMP. NSIRA will ensure that additional departments are selected for case study analysis in future years.

In completing this review, NSIRA considered legal authorities and governance frameworks. NSIRA also relied on documentation and information obtained through briefings with the departments.

NSIRA conducted a review of all twelve departments by examining relevant policy and legal frameworks as communicated by the departments.

The RCMP was responsive to NSIRA’s requests, providing documents and briefings within agreed time frames. Due to timing constraints, NSIRA relied heavily on the written record as provided. NSIRA found that overall, its expectation for responsiveness by the RCMP during this review were met.

GAC demonstrated a willingness to provide NSIRA with the information requested, and made every effort to clarify requests. GAC was timely in their responses and provided access to people and information as requested. NSIRA found that overall, its expectation for responsiveness by GAC during this review were met.

Finding 1: NSIRA finds that the Canada Border Services Agency and Public Safety Canada still have not fully implemented an ACA framework, and supporting policies and procedures are still under development.

Based on submissions to NSIRA, ten departments have established frameworks and policies addressing whether the disclosure of information to a foreign entity would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual. The submissions provided to NSIRA by Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), Department of National Defence / Canadian Armed Forces (DND/CAF), and Transport Canada (TC) indicate that they are actively working on refining existing policies and frameworks. NSIRA, in last year’s report identified Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) and Public Safety Canada (PS) as not yet having finalized their ACA policies.

CBSA advised that it has provisionally approved a framework for deciding whether a request for information from a foreign entity would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual. CBSA advised NSIRA that it issued direction to conduct an internal review with the goal of confirming the feasibility of operational implementation across multiple program areas.

PS has advised that a full suite of risk assessments are under development and that it intends to conduct information sessions to ensure other program areas not directly affected by the ACA are aware of information sharing obligations. PS also advised that the program area implicated by the Ministerial Directions (the Directions) has operationalized the policy and has ensured that their procedures and processes align with the requirements outlined in the departmental policy, Act and the Directions. These policies came into effect in January 2022, with “a few aspects” having not yet been finalized. The suite of risk assessments is still in development.

PS also intends to hold information sessions with various sections of the department that may not currently need to apply the Directions, but should nonetheless be aware of their existence should they develop new programs with an information sharing dimension.

In 2020, GAC initiated a full review of the Avoiding Mistreatment Compliance Committee (AMCC) as directed by its terms of reference. GAC has advised that notional recommendations have been developed to address the identified shortcomings. Recommendations include timeliness of Committee decisions, addressing duty of care issues, and reporting case outcomes regarding Committee decisions.

NSIRA has been advised that the AMCC’s secretariat review will be completed in 2022 and the terms of reference will be updated shortly after. In response to NSIRA’s inquires about risk analysis, GAC has advised that during the review period they created a new risk assessment form and are developing a broader orientation guide with the goal of supporting employees through the risk assessment and decision-making process. These issues are further explored in section two of this report.

RCMP has noted internal shortcomings in regards to country assessments and the inability to regularly update the reports. A framework has been provided to NSIRA on how the RCMP intends to remedy these shortcomings in the future to better serve the Foreign Information Risk Advisory Committee (FIRAC) process.

Subsection 7(1) of the Act requires deputy heads to submit a report to the appropriate Minister on the implementation of directions received under the Orders in Council during the previous year. The ACA stipulates that report submissions are required before March 01 of each year.

All twelve departments have fulfilled their obligations to report to their respective ministers The Communications Security Establishment (CSE), and TC did, however, submit their reports shortly after the March 01 deadline.

Subsection 7(2) of the Act also requires deputy heads make an unclassified version of the report available to the public as soon as feasible after submission to the Minister. Reports were made available in all of the twelve departments.

Section 8 of the Act requires the Minister to provide a copy of the report to the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICoP), NSIRA and, if applicable, the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (CRCC).

The table below captures a summary of both the departmental responses to the implementation questions and NSIRA’s assessment regarding these responses. The assessment was based on the associated details provided by departments in the context of the specific information requested. If a specific requirement was not met, it has been flagged. The relatively few instances of these were connected with departments not meeting certain reporting obligations under the Act.

| CBSA | CRA | CSE | CSIS | DFO | DND | FINTRAC | GAC | IRCC | PS | RCMP | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases referred to the deputy head? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Was a report submitted to the Minister? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the report made available to the public? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Did the Minister provide a copy to NSICoP, NSIRA, CRCC? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Finding 2: NSIRA finds that from January 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021, no cases under the ACA were escalated to deputy heads in any department.

All twelve departments indicated that they did not have any cases referred to the Deputy Head level for determination. This is a requirement of the OiC in cases where officials are unable to determine if the substantial risk can be mitigated. Therefore, all additional reporting requirements associated with this level of decision were not applicable.

| CBSA | CRA | CSE | CSIS | DFO | DND | FINTRAC | GAC | IRCC | PS | RCMP | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Level. (Supervisor/Deputy Chief) | 0 | 634 | 236 (23) | 780) | 0 | Not Known/Not Tracked | 48 | 6 | 2 | 401 | 55 | 0 |

| Second Level (Manager/Chief) | 0 | 325 | 176 (24) | 243 | 0 | Not Known/Not Tracked | 48 | 6 | 2 | 401 | 55 | 0 |

| Third Level(Director/DDG) | – | – | 8(25) | 69 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fourth Level (DG/Committee/ Working Group) | 0 | 63 | 1 (26) | 81 | 0 | 7 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 0 |

| Fifth Level (ADM/A.Commis sioner/L1) | 0 | 0 | 0 (27) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 0 |

| Sixth Level (Deputy Head) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NSIRA notes that this is the third consecutive year where there have been no cases referred to the deputy head level in any department.

Future reviews may be particularly attuned to the issue of case escalation and departmental processes for decision-making, as one of the stated objectives of NSIRA’s review of ACA obligations is to ensure that the assessment of risk is escalated to appropriate level of authority.

As part of this review, NSIRA requested information regarding the implementation of previous recommendations. The following analysis is based on responses received from departments.

In the 2019 NSIRA Review of Departmental Frameworks for Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities (2019-06), NSIRA recommended that “the definition of substantial risk should be codified in law or public direction.” NSIRA notes that some departments have accounted for this gap by relying on the definition of substantial risk in the 2017 MDs. In light of the pending statutorily mandated review of The National Security Act, 2017 (Bill C-59) and the centrality of the concept of substantial risk to the regime governing the ACA, NSIRA reiterates its 2019 recommendation that the definition of substantial risk be codified in law.

DND/CAF has advised NSIRA that as a result of its recommendation, the department has included the definition of “substantial risk” within the Chief of Defence Intelligence Functional Directive on DND/CAF Information Sharing Activities with Foreign Entities. However, it should be noted that DND/CAF has also adopted additional definitions including its definition of “foreseeable.” NSIRA has previously expressed its concerns in its 2019 detailed Annex of DND/CAF application of the MD regarding the DND/CAF interpretation of foreseeability. DND/CAF has also advised NSIRA that it leveraged the human rights assessment methodology from other organizations to develop the methodology for DND/CAF’s profiles. DND/CAF has also advised that it is actively participating with ACA-related interdepartmental working groups to share its country’s human rights methodology, procedures, and assessments, and raise concerns.

Of the twelve departments, CRA, CBSA, CSIS, DND/CAF, PS and TC have continued to adjust frameworks and policies as a result of the findings and recommendations from previous reviews of the ACA. While recommendations may not have been specific to individual departments, many have advised that they have taken into them into consideration and applied improvements more generally.

CRA for example in response to Recommendation #1 from NSIRA’s 2019 review (regarding the importance of conducting periodic internal reviews), has reviewed its exchanges of information procedures. As a result, CRA has implemented procedural changes where risk assessments deemed to be of low-risk are now approved at the manager level, whereas previously the minimum approval level was Director.

CBSA has provisionally approved its ACA policy and is currently conducting an additional review to ensure that the policy is operable across multiple program areas. CBSA has advised that the policy includes guidance on the disclosure of information, the request for information, and the use of information where there may be a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual. As part of the policy, the CBSA has incorporated procedures and processes to assess risk and coordinate with its Senior Management Risk Assessment Committee.

PS has also finalized its draft policy in response to NSIRA’s 2020 ACA review finding that it did not finalize its policy frameworks in support of the Direction received under the ACA. PS has noted that a policy was approved and came into effect on January 1, 2022. NSIRA has been advised additional aspects of the policy are still being implemented, including the development of risk assessment tools.

Finally, TC has advised NSIRA that it has taken stock of feedback on the implementation of the ACA since initial promulgation of the Corporate Policy in August 2020. TC notes that its corporate policy is under revision and seeks to clarify and strengthen key elements. TC has advised that adjustments underway include refining language to further clarify roles, responsibilities program-level requirements, and timelines associated with implementation. To this end, TC is providing more guidance on reporting format and content requirements for program-level support to the annual reporting exercise.

At the program level, TC is reviewing the policy impact of changes (over the past year) to the functional structure and roles associated with the Passenger Protect Program (PPP). To date, the PPP is the only program activity that TC has identified where risks associated with the ACA may be present. The PPP is currently transitioning to an enhanced framework, which is expected to be fully implemented prior to March 2023.

NSIRA maintains its previous recommendation that departments identify a means to establish unified and standardized country and entity risk assessment tools to support a consistent approach by departments when interacting with Foreign Entities of concern under the ACA.

The ACA review for 2021 is NSIRA’s second full year assessment of the implementation of the Act. As discussed in the background to this review, NSIRA has complemented the knowledge gained through its annual review of the ACA with an in-depth analysis of the implementation of the Directions. The in-depth analysis highlights to departments some best practices within the Government of Canada as well as some potential issues in the adopted frameworks. This year, the RCMP and GAC were selected. As one of the “original” departments subject to the 2011 Ministerial Direction, the RCMP has had over a decade to develop, implement, and adjust its framework. GAC was selected because it was issued a Ministerial Directive in 2017 and due to its role as a primary developer of human rights reports.

Finding 3: NSIRA finds that the RCMP has a robust framework in place for the triage of cases pertaining to the ACA.

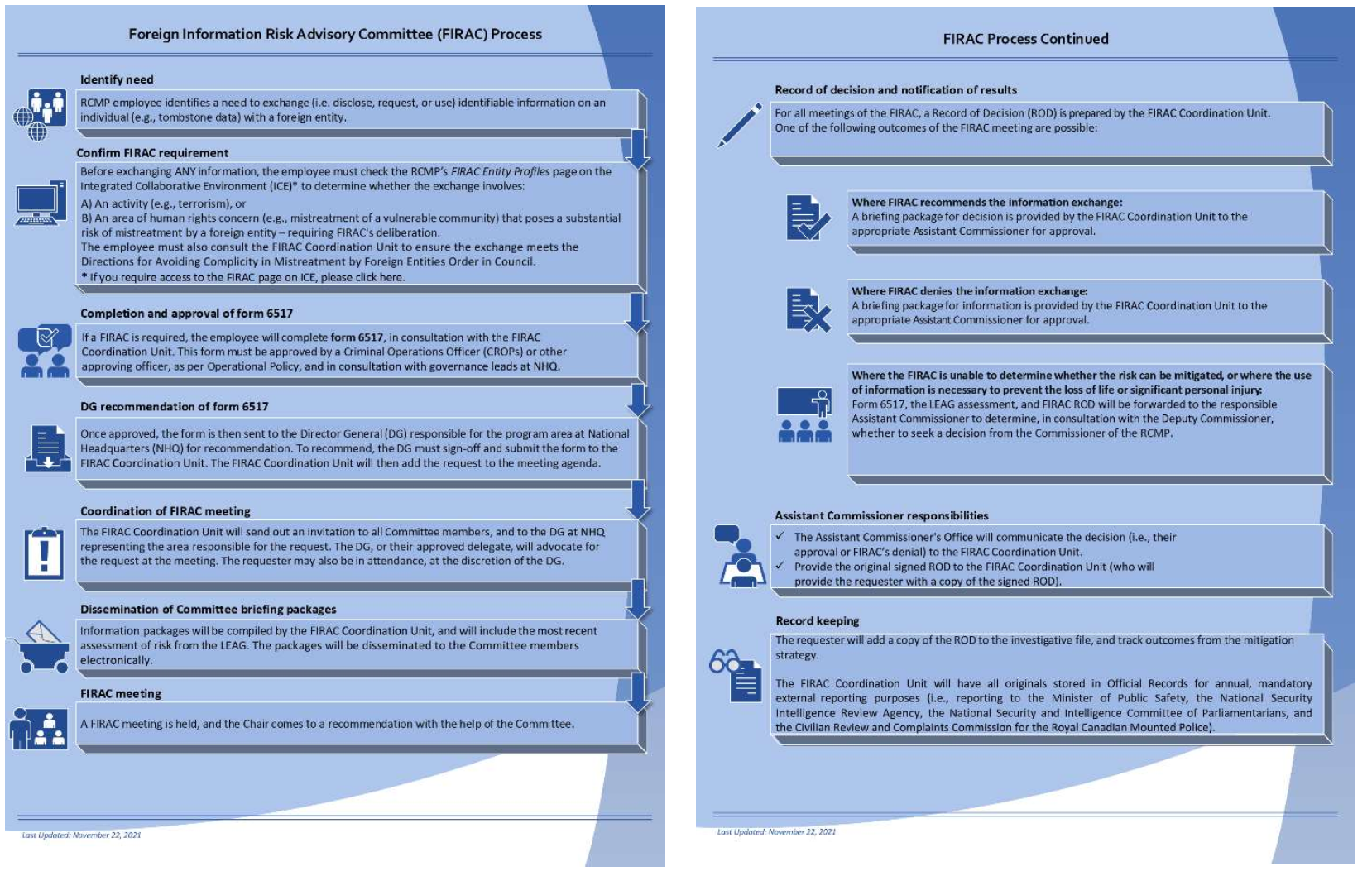

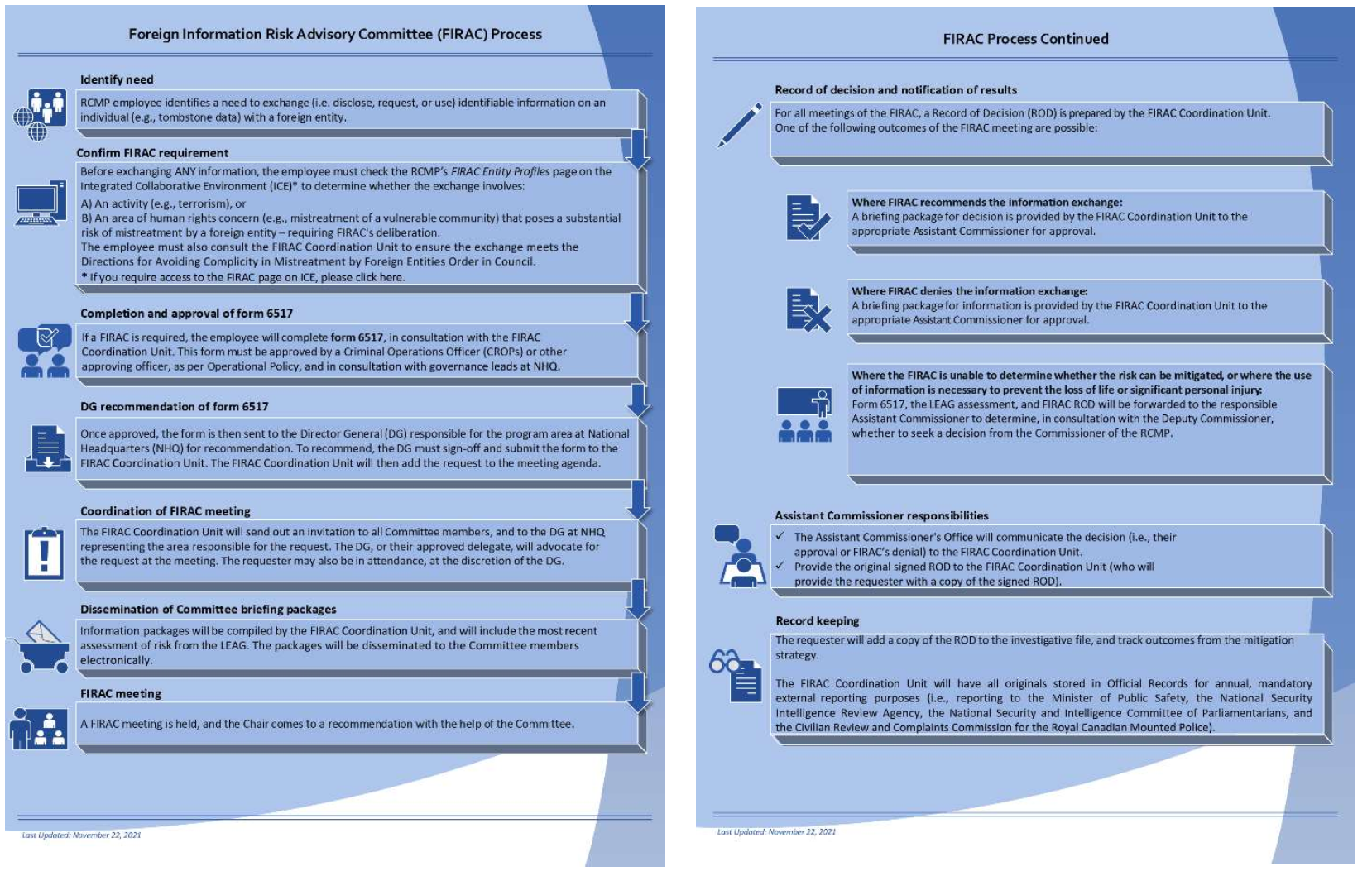

In 2011, the RCMP was issued the Ministerial Direction on Information Sharing with Foreign Entities. However the issued MD only applied to information sharing in national security matters. In response to the 2011 MD, the RCMP created the Foreign Information Risk Analysis Committee (FIRAC), the Committee was renamed the Foreign Information Risk Advisory Committee following the issuance of the 2017 MD.

The 2017 MD’s scope was broadened to include all units and personnel of the RCMP, and FIRAC was expanded accordingly. The enactment of the ACA imposed the requirement of the Orders in Council directions to the Commissioner. The operational requirements between 2017 and 2019 remained the same. The RCMP’s Implementation of the ACA is composed of three key mechanisms, FIRAC, Law Enforcement Assessment Group (LEAG), and Annual Reporting.

FIRAC is an advisory body to senior management, tasked with providing RCMP personnel with a mechanism to review information exchanges where there may be a substantial risk of mistreatment. FIRAC is a central part of the determination making mechanism for cases with ACA considerations. The committee examines the operational context of each request, the application of risk-mitigation strategies, and the strength of assurances and makes recommendations to the responsible Assistant Commissioner.

It is important to note that the Terms of Reference for FIRAC were updated in December 2021, this is after the conclusion of the last FIRAC meeting on the case study discussed below. The previous Terms of Reference which were drafted following the issuance of the 2017 MD stated that “in case of information sharing where there is a clear operational need to proceed, but a substantial risk of mistreatment, the decision will be referred to the Commissioner for final approval, as per the MD and Operational policy”. The revised Terms of Reference identifies that the Assistant Commissioner, or Executive Director is responsible for deciding whether the substantial risk of mistreatment can be mitigated. The Terms of Reference now clearly stipulates that the Assistant Commissioner, or the Executive Director as the sole decision maker, and that FIRAC fulfills an advisory function. NSIRA cautions that this apparent or perceived delegation of the final decision to the Assistant Commissioner risks non-compliance with the purpose and object of the Act and the OiC.

The Committee is comprised of two rotating chairs and a number of members from various divisions within the RCMP. As a result of an internal review, the RCMP have adjusted membership of FIRAC to ensure that co-chairs were not making determinations on cases from their respective units, with the intention of removing situations where a real or apparent conflict of interest could arise.

FIRAC meets bi-monthly or on an as-needed basis when urgent, time sensitive cases arise. All recommendations made by the committee are non-binding. NSIRA has also observed that the addition of Committee members is planned for April 2022.

Over the last year, the RCMP have made efforts to improve their framework and have created tools to aid personnel in engaging with FIRAC. They have established a FIRAC Coordination Unit, which is responsible for conducting consultations with personnel in order to help triage potential cases and determine the appropriate level of FIRAC engagement. The RCMP have also developed a suite of tools outlining definitions and thresholds, mitigation strategies and FIRAC requirements.

The FIRAC Coordination Unit works with RCMP staff, and members to assist with the risk assessment process and determine if a FIRAC evaluation is required. The Coordination Unit’s roles and responsibilities have been adjusted with the stated goal of providing guidance and support to members to strengthen case submissions. The intent of the Unit is to improve upon record keeping, identify internal strategic level issues, engage with external federal partners on cross-cutting issues to enhance processes and practices, and to share outcomes of case-specific FIRAC meetings with LEAG to inform updates on foreign entity assessments.

The RCMP is also in the final stages of updating its operational manual with the goal of supporting the Direction’s consistent application across the RCMP. This update is intended to clarify roles and responsibilities, as well as thresholds and triggers that require an information exchange to be reviewed by FIRAC.

As will be addressed later in this report, the 2019 OiC includes a requirement for the case to be referred to the RCMP Commissioner for determination, where officials are unable to determine whether the risk of sharing information can be mitigated. Additionally, pursuant to section 3(1)c of the OiC, the RCMP Commissioner must report and disclose any information considered in making the determination or decision to NSIRA, the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP (CRCC), and the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICoP) in a timely manner, if certain information that was likely obtained through the mistreatment of an individual by a foreign entity was used, in order to prevent loss of life, or significant personal injury.

The LEAG is responsible for developing country assessment profiles and maintaining the Integrated Collaborative Environment portal, where the information is stored and accessed by officers as needed. NSIRA was informed that during the last few years, the LEAG team has been severely underfunded and under-resourced, resulting in country profiles that are out of date with a third of countries having no assessment report whatsoever.

An annual report detailing the implementation of the Act and any cases brought to the Commissioner for determination must be sent to the Minister of Public Safety, NSIRA, NSICoP and the CRCC. The RCMP must also disclose any information considered in the making of a determination or decision. For full description of the RCMP’s process please see Annex A: Departmental Frameworks.

The RCMP continues to improve upon FIRAC process. Recently, the RCMP has made strides to enhance products used to assess whether proposed information exchanges carry a substantial risk of mistreatment that require FIRAC assessments. These improvements include visual tools outlining the decision-making process, key definitions, mitigation strategies, and triggers for a FIRAC evaluation.

RCMP continues to make considerable progress on updating resources on the designated SharePoint site, the ACA training module, and policy in the RCMP operational manual. While these initiatives are still in progress, NSIRA commends the RCMP’s initiative in conducting an internal review of FIRAC, and making efforts to address identified shortcomings.

Finding 4: NSIRA finds that the RCMP’s FIRAC risk assessments include objectives external to the requirements of the Orders in Council, such as the risk of not exchanging information.

Finding 5: NSIRA finds that the RCMP use of a two-part risk assessment, that of the country profile and that of the individual to determine if there is a substantial risk, including the particular circumstances of the individual in question within the risk assessment, is a best practice.

The RCMP’s information sharing framework as it relates to ACA is predicated on managing risk. While this is largely dependent on the use of assurances and caveats, investigators rely on the Liaison Officers/Analysts Deployed Overseas (LOs/ADOs) assessment of the particular country or foreign entity in question. LOs/ADOs as part of their role, are expected to provide up-to-date information on current country and entity reports, relationships established with specific entities, and the RCMP’s history as it relates to information sharing and current human rights records. Investigators use this information to help inform a mitigation measure applied to a proposed information request, and/or disclosure.

In making assessments and providing recommendations to the Assistant Commissioner, FIRAC considers the specifics of the case included in the initial risk assessment (included in the FIRAC submission), the LEAG country assessment, as well as input from the Liaison Officers/Analysts Deployed Overseas (LO/ADO). A Record of Decision is completed after each meeting and highlights the history of sharing with the entities, the risks and mitigation measures discussed, and the final recommendation of the Committee. Based on the information provided in the Record of Decision and the recommendation of the committee, the Assistant Commissioner will then make a determination.

While the RCMP has not formalized a Gender Based Analysis within their ACA risk-related assessments, NSIRA notes that considerations applied in the RCMP’s country risk assessments identify vulnerable groups at risk of mistreatment under the “Human Rights Concerns for Specific Groups.” Individuals identified as at risk in a country/entity designated as medium risk would require a FIRAC assessment prior to any information exchanges.

NSIRA sampled twenty instances where FIRAC was convened. However, there were a number of cases where multiple FIRAC meetings pertained to the same case. For example, [**redacted**] which is examined in closer detail as part of the NSIRA’s sample file review, had three separate FIRAC meetings. The twenty FIRAC instances in the selected sample amount to sixteen individual cases. Requests made by NSIRA used the FIRAC nomenclature, and the RCMP fulfilled requests based on what was requested in the Requests for Information. The result was that NSIRA was only able to view case file information where the case was a touch point within the FIRAC process; the full operational case files were not provided.

NSIRA recognizes that the RCMP fulfilled its obligation when responding to our request for information. However, when it became clear that NSIRA had not obtained the entirety of the case, including the investigative file, significant time constraints prevented NSIRA from obtaining and considering the additional information in this review.

NSIRA observed that in at least 35 percent of FIRAC cases sampled, the RCMP factored the potential for the negative impact of not sharing in their assessment. FIRAC’s assessment considers the risk of not sharing outbound information with a particular emphasis on maintaining, developing, or preserving a relationship with an information-sharing partner. Furthermore, the RCMP informed NSIRA that they will also consider the potential public risk to security of not sharing the information. NSIRA understands that the reliability of assurances and caveats depend crucially on the circumstances and the context of a particular case, but would strongly encourage the RCMP to base its rationale for sharing information primarily on the risk to the individual. NSIRA notes that the risk assessment and mitigating strategies (to minimize risk) are the primary tools to be used when assessing whether information is to be shared. The ACA and issued Orders in Council do not permit the weighing of external considerations such as relationship damage associated with not sharing information and public safety against the risk to the individual.

Finding 6: NSIRA finds that the RCMP does not have a centralized system of documenting assurances and does not regularly monitor and update the assessment of the reliability of assurances.

The RCMP advised NSIRA that any assurances or caveats that have or have not been adhered to in relation to information sharing with foreign entities are recorded within the investigative case file. The RCMP further explained that information is shared on a case-by- case basis by means of either the Liaison Officer responsible, or INTERPOL channels.

Liaison Officers/Analysts Deployed Overseas (LOs/ADOs) are required to record their interaction in their notes which would be included within the operational investigative file. The RCMP has advised NSIRA these notes are where any violations of assurances or caveats would be recorded.

The RCMP explained that it relies on its overseas network to monitor the reliability of assurances and caveats, and that personnel meet regularly with law enforcement partners and foreign allied LOs. The RCMP further noted any indication of a deterioration in human rights within a country or specific report on mistreatment of an individual would be discussed and captured within the RCMP (operational) case file, and ultimately documented in the RCMP’s FIRAC risk assessment form.

As noted above, due to time constraints, NSIRA obtained information on FIRAC meetings and the supporting documents, and did not have an opportunity to review the RCMP’s operational case files. When NSIRA asked to provide rationales used to assess the reliability of assurances and caveats for the selected sample, NSIRA was referred back to the FIRAC risk assessment form (also known as Form 6517), and provided with the following:

The footnote highlights a number of case files. General and Supplementary reports on these files were reviewed in the preparation of this response. No concerns with respect to assurances were documented and only one instance with respect to caveats was identified. In this regard, [**redacted**] documents one instance wherein a partner agency had not adhered to a caveat’s requirement to coordinate actions – no allegation of mistreatment was documented on the file. The issue was raised with the partner agency and addressed.

NSIRA notes that while the [**redacted**] was in relation to a company operating in the [**redacted**], witness information was sought from the [**redacted**]. The LEAG Country Risk Assessment for [**redacted**], designated as medium risk, does cite an issue specific to the sharing of information and the use of caveats, but has not been updated since August 2018. The RCMP has advised that:

While the LEAG country assessment has not yet been updated, the LO would be expected to raise this issue in any future consultations with various investigative teams seeking to share with this entity.

NSIRA stresses the importance of the post-monitoring of assurances and caveats. NSIRA has observed that the issuance of an assurance, and/or caveat may sometimes rely on assurances provided by a specific official (within the foreign entity/country). Absent appropriate documentation, this may be problematic due to the fact that movement within positions is to be expected and assurances can no longer be valid if the individual has moved out of the position. Assurances must be followed up on and renewed to ensure they are being followed in the event of employee turnover.

Furthermore, there is no centralized process for the documentation of assurances. Rather, some documentation that is occasionally noted on specific investigative files may be problematic in situations where LOs/ADOs are rotational. If the investigative file is closed, the new LOs/ADOs to the post may not be aware of situations where assurances have not been respected.

Recommendation 1: NSIRA recommends that the RCMP establish a centralized system to track caveats and assurances provided by foreign entities and where possible to monitor and document whether said caveats and assurances were respected.

Finding 7: NSIRA finds that the RCMP does not regularly update, or have a schedule to update its Country and Entity Assessments. In many cases these assessments are more than four years old and are heavily dependent on an aggregation of open source reporting.

Finding 8: NSIRA finds that information collected through the Liaison Officer in the course of an operation is not centrally documented such that it can inform future assessments.

In 2019, the RCMP conducted an internal review of its information sharing framework including LEAG and FIRAC. Based on this review, NSIRA recommended in 2019, that departments adopt internal reviews of their policies and processes as a best practice. While it is not the intention to cover items already identified in the (internal) review, NSIRA notes that three years have elapsed and the issues associated to country and entity assessments still remain.

Of the 90 assessments, the RCMP is currently using to base its risk assessments, 87 percent have not been updated since 2018, and the remaining thirteen percent have not been updated since 2019. Over the course of 2021, the RCMP did not update any of its country profiles. NSIRA has been advised that in 2022, [**redacted**] but cite funding constraints as a key challenge.

A key finding of the RCMP’s internal review relates composition of the profiles themselves, in that they: “do not sufficiently reflect the RCMP’s operational experience.” The review states that: “LEAG country and entity risk profiles are predominately based on open source information rather than input from operational units…” The RCMP through the course of the review emphasized the role and importance to the Liaison Officer during the FIRAC process, suggesting that the Liaison Officer is positioned to offset any shortcoming with the country and entity profiles. NSIRA notes the internal review highlights some of the challenges faced by the Liaison Officers, referring to the added responsibilities of the LEAG and the FIRAC processes as adversely affecting their ability to preform their regular duties.

NSIRA notes the RCMP’s ongoing efforts at improving its post-monitoring efforts. NSIRA looks forward to reviewing the progress made over the next year on the measures taken on updating the RCMP’s country profiles, and inclusion of post-monitoring of automating media monitoring and information sharing tracking mechanism with INTERPOL Ottawa.

[**redacted**] the RCMP sought approval to interview a [**redacted**]

[**redacted**] The RCMP sought to [**redacted**] interview [**redacted**] in order to assess the current risk or threat [**redacted**] to Canada and Canadian citizens, [**redacted**]. The RCMP has advised that a “…successful interview could advance the investigation [**redacted**]and significantly improve the ability to identify the threat and risk [**redacted**] to [**redacted**] security.”

Additionally, the RCMP believed that “engagement with [**redacted**] may lead to [**redacted**] information and evidence [**redacted**].

[**redacted**]

The RCMP’s internal Country profile classifies [**redacted**] as a High-Risk Profile (RED). The profile notes serious documented allegations of human rights abuses [**redacted**] (but not limited to) torture [**redacted**] suspects routinely subjected to unfair trials. The RCMP had concerns that “If [**redacted**] could face torture and mistreatment [**redacted**]”. As per policy the case was escalated to the Foreign Information Risk Advisory Committee (FIRAC).

[**redacted**], the FIRAC convened and discussed the request to interview [**redacted**] Committee found that there are substantial risks of mistreatment for [**redacted**] that there are currently no measures in place that could effectively mitigate the identified risks. FIRAC noted [**redacted**].

FIRAC did however also note, “that efforts should be made to better position possible future interviews.” They noted that [**redacted**] would “allow the RCMP to monitor the outcomes and assurances of discussions at a strategic level [**redacted**].

Accordingly, FIRAC recommended that the RCMP “engage in discussion [**redacted**] on the [**redacted**] potential for [**redacted**]. The Assistant Commissioner for [**redacted**] approved this recommendation.

In response to the FIRAC recommendation, senior RCMP [**redacted**]

[**redacted**]

Based on [**redacted**] the investigative team sought FIRAC’s recommendation to allow [**redacted**] further discussions [**redacted**] in order to have the RCMP [**redacted**] interview with [**redacted**] and seek assurances [**redacted**].

[**redacted**]

[**redacted**], the FIRAC convened [**redacted**] to consider the request to engage and exchange information to [**redacted**] interview [**redacted**] to seek assurances [**redacted**]. The request was approved by FIRAC, if certain mitigation measures and assurances be received, [**redacted**].

[**redacted**] RCMP [**redacted**] engaged the [**redacted**]. The RCMP [**redacted**] there is a [**redacted**] they would be interested in interviewing [**redacted**].

[**redacted**]

[**redacted**]

[**redacted**]

[**redacted**]

[**redacted**]

The RCMP [**redacted**] escalated the requests to interview [**redacted**] to FIRAC with additional mitigation measures.

[**redacted**]

[**redacted**]

FIRAC convened a meeting to discuss the request to share the personal information of [**redacted**].

The Committee concluded that there is a substantial risk of mistreatment [**redacted**] should the information be shared and that said risk cannot be mitigated by caveats and assurances. Accordingly, the Committee recommended that the information not be exchanged. This recommendation was based on the following concerns:

FIRAC recommended [**redacted**] explore additional options to reduce the potential risk of mistreatment and then return to the committee for reconsideration. Among these options, the Committee suggested [**redacted**].

[**redacted**], the Assistant Commissioner [**redacted**] rejected FIRAC’s recommendation and allowed the sharing of information. He based his decision on the following:

The Assistant Commissioner then concludes, “failure to share presents risk that cannot be managed [**redacted**]. Although influence is not guaranteed, I believe it is the better choice”

A subsequent email by the Assistant Commissioner [**redacted**] outlined additional considerations that factored into the decision to reject FIRAC’s recommendations. These considerations focused on the risk of not sharing the information. The additional information included operational and strategic considerations [**redacted**]. The Assistant Commissioner stated that lack of engagement [**redacted**]. Strategically, the Assistant Commissioner noted the risk to relationship should the information not be shared, noting that “failure to follow through [**redacted**] and associated mitigation efforts articulated below will likely have a negative impact on the [**redacted**] relationship [**redacted**].

The Assistant Commissioner’s reasoning goes on to include a “necessity” analysis regarding the challenges [**redacted**] the importance of the information from the interview, and the importance of the relationship [**redacted**]. Of note, the Assistant Commissioner notes that [**redacted**] a strong relationship [**redacted**] will aid in plans to mitigate the greater risk while also managing the risk that exists today for the Canadian [**redacted**]. The Assistant Commissioner also concludes his email by stressing that it is his belief that sharing the information is required to reduce the risk of mistreatment [**redacted**] that lack of involvement will lead to greater risk.

Finding 9: NSIRA finds that FIRAC members concluded that the information sharing would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment that could not be mitigated. The Assistant Commissioner determined that it may be mitigated. This amounts to a disagreement between officials or a situation where “officials are unable to determine whether the risk can be mitigated.”

The ACA and issued OIC place an absolute prohibition on the sharing of information where there is a substantial risk of mistreatment of an individual. Unless “officials determine that the risk can be mitigated, such as through the use of caveats or assurances and appropriate measures are taken to mitigate the risk”, the information cannot be disclosed. Section 1(2) of the OICs further stipulate, “that where officials are unable to determine whether the risk can be mitigated, the Commissioner must ensure that the matter is referred to the Commissioner for determination.”

The Assistant Commissioner’s decision to share the information contrary to FIRAC’s recommendation, cites section 1(2) of the OIC and concludes that since the FIRAC is responsible for making a recommendation to the Assistant Commissioner then the Assistant Commissioner is the final decision maker. The Assistant Commissioner “made the decision that the risk can be mitigated.” The Assistant Commissioner did not consider that making the final decision in this instance ran contrary to the process set out in the FIRAC Terms of Reference, and contrary to the OICs. The OICs are clear, where officials are unable to determine whether the risk can be mitigated the matter must be referred to the Commissioner…” Accordingly, pursuant to section 1(2) of the OIC, NSIRA notes that this case should have been elevated to the Commissioner for determination.

Finding 10: NSIRA finds that the Assistant Commissioner’s rationale for rejecting FIRAC’s advice did not adequately address concerns consistent with the provisions of the Orders in Council. In particular, NSIRA finds that the Assistant Commissioner erroneously considered the importance of the potential future strategic relationship with a foreign entity in the assessment of potential risk of mistreatment of the individual.

[**redacted**]

A number of assumptions characterize the justifications by the Assistant Commissioner to share the requested information.

[**redacted**]. However, this reasoning disregards [**redacted**]. It further dismisses the RCMP’s own reporting [**redacted**]. FIRAC’s record of decision which notes, [**redacted**]. The Assistant Commissioner accordingly disregards the possibility that [**redacted**].

In the alternative, the Assistant Commissioner relies on [**redacted**] but does not consider now the risk [**redacted**] may increase [**redacted**].

Secondly, the Assistant Commissioner’s reasoning relied on [**redacted**].

The Assistant Commissioner does not address FIRAC’s concerns for [**redacted**] the insufficiency of mitigation measures. Rather the Assistant Commissioner concludes [**redacted**] greater risk should the information not be shared – but does not explain why or how so? Nor does the Assistant Commissioner address FIRAC’s concerns regarding [**redacted**].

Additionally, the Assistant Commissioner’s decision considered and emphasized the importance of the relationship between the RCMP [**redacted**] While FIRAC expressed concern assurances would be respected. The Assistant Commissioner’s reasoning focuses on the importance of [**redacted**], that relationship [**redacted**].

As mentioned earlier, according to the RCMP:

“…while the ACA and OiC may not speak to external considerations, it does not prohibit strategic considerations as part of the totality of the analysis, rather than against the risk to the individual, including whether strategic partnerships may act as a mitigation measure. It is important to note that the ACA and OiC do not supersede our obligations under the RCMP Act.”

The RCMP further noted that: “…As such, any action or inaction could result in unwanted consequences, and to include them as a consideration to demonstrate due diligence, and that all aspects of an activity is considered is prudent. Strategic relationships, or more importantly, in this case, actions that jeopardize the strategic relationship, can lead to harm. The A/C clearly stated that.”

NSIRA notes that the assessment of mistreatment must be limited to whether the disclosure would result in a substantial risk of mistreatment to the individual and whether said risk may be mitigated. NSIRA strongly cautions against the use of additional considerations such as strategic relationships in the assessment of substantial risk.

It should be noted that the Assistant Commissioner did provide additional mitigation measures for consideration. However, those measures were all premised on [**redacted**]. The measures did not require that the assurances and the FIRAC suggested mitigation measures be adopted as a prerequisite to the information sharing.

Recommendation 2: NSIRA recommends that in cases where the RCMP Assistant Commissioner disagrees with FIRAC’s recommendation not to share the information, the case be automatically referred to the Commissioner.

Recommendation 3: NSIRA recommends that the assessment of substantial risk be limited to the provisions of the Orders in Council – namely the substantial risk of mistreatment and whether the risk may be mitigated – and external objectives such as fostering strategic relationships should not factor into this decision-making.

Finally, in the case at hand the Assistant Commissioner responsible for approving the FIRAC recommendations was the same Assistant Commissioner supervising the business line of the case. In 2019 NSIRA recommended that “departments should ensure that in cases where the risk of mistreatment approaches the threshold of “substantial”, decisions are made independently of operational personnel directly invested in the outcome.” As discussed in paragraph 61 above, in 2021 the RCMP adjusted its FIRAC process such that there are co-chairs for the FIRAC. Adding an additional Chair (co-chairs) was to ensure that the Chair overseeing a specific FIRAC is not the one responsible for business line where the case originated. The case at hand demonstrates the need to emulate that structure at the senior level in order to maintain independent decision-making and ensure that the case focus is on the substantial risk of mistreatment to the individual rather than additional strategic considerations.

Recommendation 4: NSIRA recommends that FIRAC recommendations are referred to an Assistant Commissioner who is not responsible for the branch from which the case originates.

During the course of the review period from January 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021, six cases reported to having been referred to the Intelligence Policy and Programs Division (INPL) for further assessment. In the cases that were provided to NSIRA all were specific to Mission security, where Missions were dependent on local authorities to assist in situations where there was a potential threat to staff at the embassy or consulate. When asked about the low number of cases, GAC advised NSIRA that sharing personal identifying information with foreign entities was very rare in an ACA context.

Finding 11: NSIRA finds that GAC is now strongly dependent on operational staff and Heads of Mission for decision-making and accountability under the ACA.

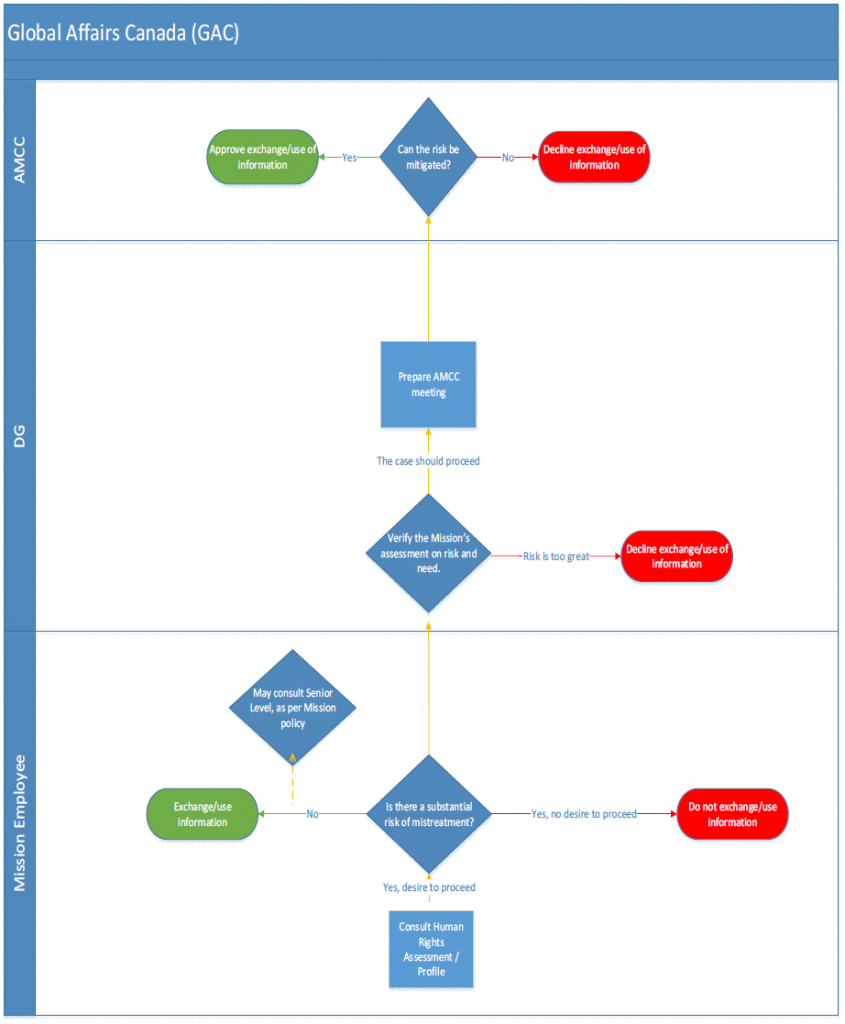

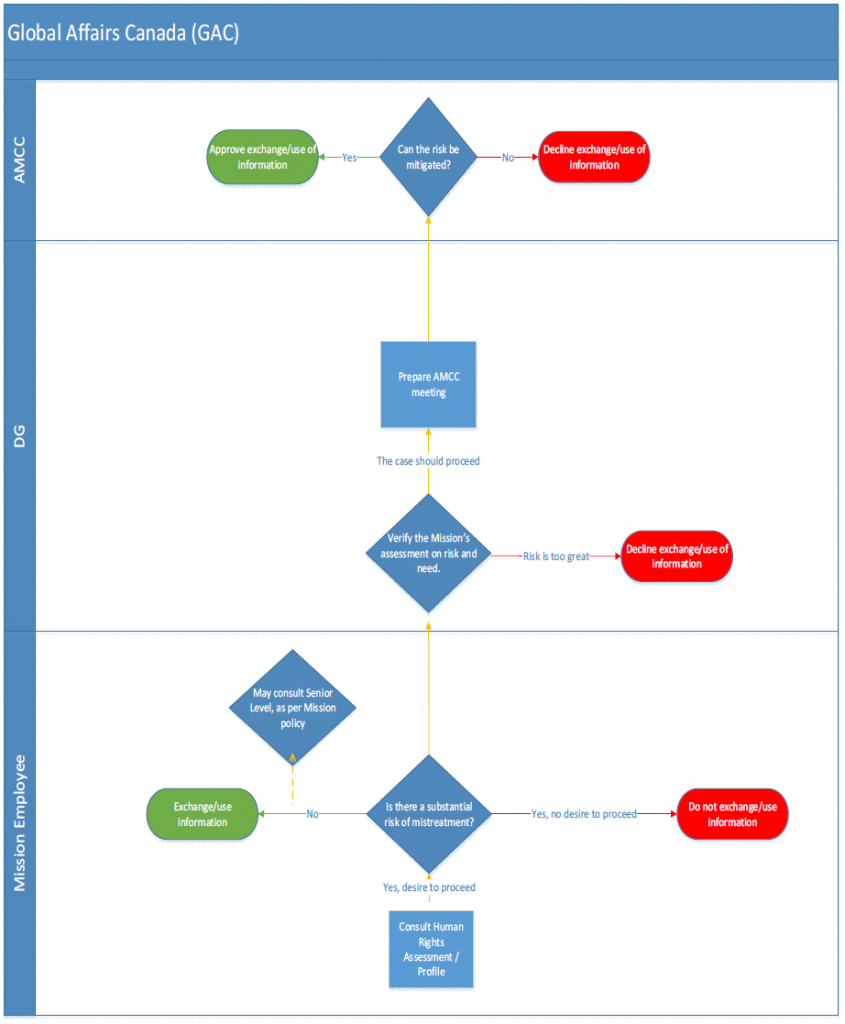

On December 14, 2017, GAC was issued Ministerial Direction on Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities (2017 MD). GAC had not received the Ministerial Direction on Information Sharing with Foreign entities (the 2011 MD) that was issued to a number of other departments.

The department manages a global network of over 175 missions in 110 countries, employing approximately 12,000 staff with an operating with a budget of over $7 billion.

When asked how the department operationalizes the Act, GAC referred to their outreach and training programs. GAC advised NSIRA that their training programs targeted specific staff to ensure awareness of and compliance with the ACA. The training outlines the roles and responsibilities regarding the ACA and Orders in Council requirements, and provides employees a definition of “substantial risk,” and points of contact at headquarters.

In 2021, NSIRA committed to further scrutinizing the processes regarding ACA triage and decision-making by reviewing both GAC and the RCMP. In the 2020 ACA review, NSIRA found that there were significant divergences in the evaluation of risk and required level of approvals across departments. In particular, NSIRA identified procedural gaps in GAC’s risk assessments that should have warranted escalation to the Deputy Minister.

When asked if GAC had initiated any adjustments, or changes to frameworks or policies as a result of the findings and recommendations from previous reviews of the ACA, GAC advised that adjustments had been made to the framework by creating a Mistreatment Risk Assessment form. They explained that the form would support the application of a more consistent threshold for elevating a case in the decision-making process, and would standardize how cases are documented. As of August 31, 2022, GAC has yet to implement the use of this form.

Currently, the Head of Mission (HoM, or Chargé) makes the initial assessment in determining if the risk of mistreatment to the individual may be mitigated below the substantial risk threshold. Only where the HoM identifies a concern as to the sufficiency of the mitigation measures or assessment, would the HoM seek guidance through the Intelligence Policy and Programs Division (INPL) generic e-mail.

INPL can assist the Mission in conducting a risk assessment. If at this point it is determined there is a substantial risk of mistreatment that cannot be mitigated and the Mission still wants to proceed, the responsible geographic Director General may request that the Avoiding Mistreatment Compliance Committee (AMCC) be convened. The AMCC provides a decision to the HoM. GAC has advised that the role of the AMCC:

….is to recommend risk-mitigation strategies, seek escalatory senior-level discussion and approval for decisions as required, up to and including the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, and document how each case is managed. It is convened on an ad hoc basis to review the proposed disclosure, request, or use of information in cases in which prohibitions under the Directions may be engaged. The Committee is similar to structures that exist within other departments and agencies subject to the OiC.

In 2020 and 2021, GAC initiated a review of the Secretariat of the AMCC, formerly known as the Ministerial Direction Compliance Committee (MDCC). GAC has advised that notional recommendations have been developed to improve the working methods of the Committee and update the terms of reference. Explaining that the timeliness of Committee decisions, addressing duty of care issues, and final reporting of case outcomes regarding Committee decisions are currently being examined. It is expected that the AMCC Secretariat’s review will be completed in 2022 and the terms of reference updated shortly thereafter.

In the six cases provided over the review period, NSIRA observed that the final decision on whether to share information with local authorities was left to the HoM. This is best illustrated in the HANOI case where the mission was advised

To note, decision-making authority on such situations ultimately rests with mission/geo. INPL’s role—as departmental focal point for the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACMFEA)—is simply to advise on relevant considerations, not authorize.

In further correspondence between INPL and the Mission in Hanoi there appears to be the need for additional clarification on the decision-making roles in regards to applying the ACA. INPL further advised the Mission that “it is in fact the Mission’s responsibility to determine if there is a substantial risk of mistreatment or not.”

The centralization of accountability with the HoM as opposed to headquarters represents a significant change in implementation since NSIRA’s in-depth review of GAC in 2019. Namely, in the previous review any cases where there was a potential substantial risk of mistreatment would require escalation MDCC (via the INPL) where the Committee would ultimately be responsible for deterring if the proposed mitigation measures are sufficient and if the information sharing should take place. This change in implementation threatens the independence of the process from individuals with a potential operational interest in the outcome of the information sharing.

Recommendation 5: NSIRA recommends that GAC ensure that accountability for compliance with the ACA clearly rests with the Avoiding Mistreatment Compliance Committee.

Finding 12: NSIRA finds that GAC has not demonstrated that all of its business lines are integrated into its framework under the ACA.

GAC does not have any information-sharing arrangements with foreign entities related to the ACA. When asked in last year’s review how GAC monitors its information exchanges, the response provided reads as follows:

There is a handful of divisions at GAC that receive information that may have been obtained through mistreatment. Because of the very different type of information they each receive due to their specific mandates, each has a different process/framework for identifying information likely to have been obtained through the mistreatment. Therefore, there is not one unified set of processes at GAC for initially marking/identifying incoming information potentially derived from mistreatment.

GAC has also not conducted an internal mapping exercise to determine which business lines are subject to the ACA. Considering the low number of cases this year and the size of GAC, and that ACA training is not mandatory for staff, NSIRA has concerns that not all areas involved in information sharing within GAC are being properly informed of their ACA obligations.

When asked to elaborate on the nature of information exchanges triggering the ACA, GAC further clarified:

[T]hat information exchanges occur without formal arrangement with foreign entities, and the vast majority of the information that is exchanged does not pertain to individuals. Each information exchange situation is unique and occurs within a specific relational and country context.

Each instance of information sharing is handled on a case-by-case basis and escalated to the appropriate level based on the individual circumstances.

It is important to note that if the assessment determines that there is NOT a substantial risk of mistreatment, but that the exchange of information directly or indirectly involves personally identifiable information about an individual AND the country or foreign entities is not a trusted partner when it comes to human rights, GAC employees must still capture via a risk assessment form the reason why there is NOT a substantial risk of mistreatment and keep a thorough record.

Finding 13: NSIRA finds that GAC has not made ACA training mandatory for all staff across relevant business lines. This could result in staff being involved in information exchanges without the proper training and knowledge of the implications of the ACA.

When determining whether there is a risk of mistreatment, GAC employees will leverage human rights reports, as well as any intelligence relevant to the country/entity associated with the information. The risk profile of the individual about whom information is shared is also taken into consideration when making a determination regarding whether a substantial risk of mistreatment exists. It is a collection of information that informs any assessment and respective decision, rather than a single tool.

Training is only mandatory for employees working in a high-risk mission or functions and offered as a suggestion for other staff at mission and headquarters. GAC has committed to establishing a dedicated ACA page on the intranet, along with supporting communication, however, employees are only encouraged to review it.

GAC provides an outreach program and training, for staff both at headquarters and at missions abroad on their ACA obligations. The ACA components are embedded in GAC’s Governance, Accreditation, Technical Security and Espionage (GATE) awareness program, the Legal and Policy Framework on Information Sharing, and a module in the Heads of Mission pre-posting training. These training courses outline the roles and responsibilities of officials regarding their ACA and Orders in Council obligations, including the definition of “substantial risk”, and key points of contact at headquarters. It is important to note that the GATE awareness program and that the ACA segment of the training is considered as an outreach tool and not a core training module, meant to provide situational awareness for Canadian- based staff on information security and intelligence topics. The training provided by the Department of Justice acts as the core training module for staff.

When asked about Consular Operations bureau training, GAC appeared to have only a cursory knowledge citing that they were aware from the 2021 Annual Report (on the Application of the Orders in Council Directions for Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities) that ACA directions were included as part of the training session offered by the Consular Operations bureau.

The target employees for training at headquarters are outgoing Mission Security Officers, Management Consular Officers, Readiness Program Managers, Global Security Reporting Program Officers and Heads of Mission, as well as all members of the Intelligence Bureau. At mission, the training is provided to all Canada-based staff, including other government departments’ employees posted at missions. GAC has only recently begun tracking the number of staff that have been provided ACA training, and estimates that at least 300 GAC employees have been provided ACA-related training since 2020.

When further queried about the breakdowns of training provided, GAC posited that there are only a small proportion of GAC officers abroad that may encounter ACA-related decisions. With training only mandatory for some staff, NSIRA is concerned that given the volume of information exchanges, and the multiplicity of business lines there is very well potential that information sharing may be occurring, or not properly triggered by those without proper ACA knowledge.

In light of the fact that GAC engages with foreign entities with poor human rights records and operates in highly volatile environments, NSIRA expresses deep concern that GAC has not demonstrated that it has implemented ACA framework across business lines.

Recommendation 6: NSIRA recommends that GAC conduct a formal internal mapping exercise of other possibly implicated business lines to ensure it is meeting its obligations set out in the ACA.

Recommendation 7: NSIRA recommends that GAC make ACA training mandatory for all rotational staff.

Finding 14: NSIRA finds that GAC has not regularly updated its Human Rights Reports. While many were updated during the 2021 review year, more than half have not been updated since 2019. This is particularly problematic when departments and agencies rely on these reports as a key source in assessing risk related to the ACA.

GAC develops classified human rights reports making them available to a number of internal Government of Canada partners. These reports are intended to provide an overview of the human rights situation of a particular country. They help inform Canada’s international engagement and programming decisions, including foreign policy, development, trade, security, and consular activities. Updated human rights reports (post 2019) include a designated section that addresses the Orders in Council and the ACA, and the circumstances of mistreatment within that country.

The coming into force of the ACA and the issuance of the Orders in Council resulted in a greater number of departments being subject to directions specific to the avoidance of mistreatment by foreign entities. Many of these departments did not have frameworks or any country assessments to support this obligation. This created an increased demand for the GAC Human Rights Reports.

Prior to Royal Assent of the ACA, GAC provided human rights reports to departments that were subject to the 2017 Ministerial Directives. GAC also works with partners to incorporate feedback on human rights reporting and considers input on countries of interest for subsequent reporting cycles. It is important to note that GAC does not keep statistics on how often, or which reports were requested/accessed by internal partners.

NSIRA recognizes that in 2021 GAC has recently implemented a prioritized list to update the human rights reports and has been making considerable headway during the review period, updating 25 percent of their profiles. A number of high-risk countries have been updated to reflect current events. Still, a number of reports are outdated and close to 60 percent of the 133 human rights reports have not been updated since 2019. For example, Pakistan, Somalia, Ukraine, and Yemen have not been updated since 2019, while South Africa and Belarus have not been reviewed since 2015.

Maintaining up-to-date reports will help ensure that critical human rights information is being used when making ACA determinations, this is especially vital considering that other department leverage GAC’s human rights report as part of their risk assessments. NSIRA notes that the Information Sharing Coordination Group coordinated by Public Safety Canada continues to work through the prioritization and the issues associated with the sharing of human rights reports across departments. It should be stressed that the GAC human rights reports are viewed as a supplement to what departments have already collected as part of their own assessments. For this reason GAC does not provide evaluative judgment on risk within their human rights reports, that is they do not designate whether a country or entity is high or low risk, consequently leaving departments to assess risk based on the information they have collected as part of their mandates.

NSIRA has been advised that the GAC country priority list was developed in consultation with partner departments and agencies, and relevant GAC divisions. And is based on an assessment of the operational needs of Canadian federal departments and agencies. While understanding the impact the pandemic had on operations, particularly at Missions abroad, NSIRA encourages GAC to develop, maintain, and continue to work with other departments and agencies to ensure countries’ HRRs are updated as regularly as possible.

GAC produces human rights reports in collaboration with its missions. Coordinated by GAC’s office of Human Rights, Freedoms and Inclusion directorate, the reports are used not only to inform risk assessments, but assist in the guidance of policy and programming decisions.

Missions are responsible for updating their human rights reports, and, if tasked, are linked to Head of Mission’s performance measurement agreements. Mission staff work collaboratively with geographic branches in the preparation of the reports. While headquarters is responsible for the tasking and coordination of the reports, it is Head of Mission that approves the report. The reports include information on the overall human rights context in the country, as well as an analysis of the significant human rights-related events that took place during the review period. Generally, reports are a collection of various sources, which include open source reporting, consultations with human rights organizations and civil society partners, and engagement with government authorities and stakeholders.

Recommendation 8: NSIRA recommends that GAC ensure countries’ Human Rights Reports are updated more regularly to ensure evolving human rights related issues are captured.

Finding 15: NSIRA finds that GAC does not have a standardized centralized approach for the tracking and documentation of assurances.

GAC advised that there was no standardized approach in place to assess the reliability or document assurances received from foreign entities. Risk assessments are conducted on a case-by-case basis. When asked how assurances were developed, GAC stated that there was no statutory or regulatory language that specifically addressed the use of diplomatic assurances, but officials implicated in individual cases would consider the foreign entity’s credibility, recent precedents, the experiences of like-minded partners, and the feasibility of monitoring assurances and caveats to be communicated with the disclosure. It is the Mission’s responsibility to track and monitor whether assurances and caveats are being respected

NSIRA noted that on the ATHENS case provided by GAC, there was a concerted effort to ensure assurances and caveats were in place before information was shared with local authorities. It is in NSIRA’s opinion that the mission was attuned to their obligations under the Act (and directions) and tried to ensure the welfare of the individual detained by authorities. [**redacted**] Mission staff took remedial action to ensure that the individual is not at risk of mistreatment.

In the ATHENS case, [**redacted**]. NSIRA noted that there is no formalized tracking, or documentation mechanism for the follow-up caveats and assurances. This is problematic as mission staff are rotational and may therefore have no visibility as to their ability to rely on caveats and assurances based on past information sharing instances.

Recommendation 9: NSIRA recommends that GAC establish a centralized system to track caveats and assurances provided by foreign entities and document any instances of non-compliance for use in future risk assessments.

Finding 1: NSIRA finds that the Canada Border Services Agency and Public Safety Canada still have not fully implemented an ACA framework and supporting policies and procedures are still under development.

Finding 2: NSIRA finds that from January 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021, no cases under the ACA were escalated to deputy heads in any department.

Finding 3: NSIRA finds that the RCMP has a robust framework in place for the triage of cases pertaining to the ACA.

Finding 4: NSIRA finds that the RCMP’s FIRAC risk assessments include objectives external to the requirements of the Orders in Council, such as the risk of not exchanging information.

Finding 5: NSIRA finds that the RCMP use of a two-part risk assessment, that of the country profile and that of the individual to determine if there is a substantial risk, including the particular circumstances of the individual in question within the risk assessment is a best practice.

Finding 6: NSIRA finds that the RCMP does not have a centralized system of documenting assurances and does not regularly monitor and update the assessment of the reliability of assurances.

Finding 7: NSIRA finds that the RCMP does not regularly update, or have a schedule to update its Country and Entity Assessments. In many cases these assessments are more than four years old and are heavily dependent on an aggregation of open source reporting.