Date of Publishing:

Executive Summary

The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)’s Air Passenger Targeting program performs pre-arrival risk assessments on inbound passengers. It seeks to identify passengers that may be at higher risk of being inadmissible to Canada or of otherwise contravening the CBSA’s program legislation. It does so by using information submitted by commercial air carriers called Advanced Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data in a multi-stage process that involves manual and automated triaging methods, referred to as Flight List Targeting and Scenario Based Targeting.

The Advance Passenger Information and/or Passenger Name Record data used to perform these prearrival risk assessments include personal information about passengers that relates to prohibited grounds of discrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter). These grounds include age, sex, and national or ethnic origin. The CBSA relies on information and intelligence from a variety of different sources to determine which of these data elements indicate a risk in passengers’ characteristics and travel patterns in the context of specific enforcement issues, including national security-related risks. Given their potential importance for Canada’s national security and for the CBSA’s concurrent obligations to avoid discrimination, attention to the validity of the inferences underpinning the CBSA’s reliance on the particular indicators it creates from this passenger data to perform these risk assessments is warranted. These considerations also have implications for Canada’s international commitments to combat terrorism and serious transnational crime and to respect privacy and human rights in the processing of passenger information.

NSIRA conducted an in-depth assessment of the lawfulness of the CBSA’s activities in the first step of the pre-arrival risk assessment, where inbound passengers are triaged using the passenger data provided by commercial air carriers. The review examined whether the CBSA complies with restrictions established in statutes and regulations on the use of the Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data and whether the CBSA complies with its obligations pertaining to non-discrimination.

While NSIRA found that the CBSA’s use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data complied with the Customs Act, the CBSA does not document its triaging activities in a manner that enables effective verification of compliance with regulatory restrictions established under the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations. This was more of a weakness in the CBSA’s manual Flight List Targeting triaging method than its automated Scenario Based Targeting method.

The CBSA was also unable to consistently demonstrate that an adequate justification exists for its reliance on particular indicators it created from the Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data to triage passengers. This is important, as the CBSA’s reliance on certain indicators results in drawing distinctions between travellers based on prohibited grounds of discrimination. These distinctions may lead to adverse impacts on passengers’ time, privacy, and equal treatment, which may be capable of reinforcing, perpetuating or exacerbating a disadvantage. Adequate justification for such adverse differentiation is needed to demonstrate that such distinctions are not discriminatory and are a reasonable limit on travellers’ equality rights.

Recordkeeping is important to ensure effective verification that Air Passenger Targeting triaging activities comply with the law and respect human rights and NSIRA observed important weaknesses in this regard. These recordkeeping weaknesses stem in part from the fact that the CBSA’s policies, procedures, and training are insufficiently detailed to adequately equip CBSA staff to identify discrimination and compliance-related risks and to act appropriately in their duties. Oversight structures and practices are also not rigorous enough to identify and mitigate potential compliance and discrimination-related risks. This is compounded by lack of collection and assessment of relevant data. NSIRA recommends improved documentation practices for triaging to demonstrate compliance with statutory and regulatory restrictions and to demonstrate that an adequate justification exists for its reliance on the indicators it creates from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data. Such documentation is essential to enable effective internal oversight as well as external review.

NSIRA also recommends more robust training and increased oversight to ensure that triaging practices are not discriminatory. This should include updates to policies as appropriate as well as the collection and analysis of the data necessary to identify, analyze and mitigate discrimination-related risks

Front matter

Lists of acronyms

| API | Advance Passenger Information |

| APT | Air Passenger Targeting |

| CBSA | Canada Border Services Agency |

| CHRA COVID-19 EU | Canadian Human Rights ActNovel Coronavirus/Coronavirus Disease of 2019European Union |

| FLT | Flight List Targeting |

| IATA | International Air Transport Association |

| ICES | Integrated Customs Enforcement System |

| IRPA | Immigration and Refugee Protection Act |

| IRPR | Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations |

| MOU | Memorandum of Understanding |

| NSIRA | National Security and Intelligence Review Agency |

| OAG | Office of the Auditor General of Canada |

| OPC | Office of the Privacy Commissioner |

| PAXIS | Passenger Information System |

| PCLMTFA | Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act |

| PICR | Passenger Information (Customs) Regulations |

| PNR | Passenger Name Record |

| PPIR | Protection of Passenger Information Regulations |

| RFI | Request for Information |

| SBT | Scenario Based Targeting |

| SOP | Standard Operating Procedures |

| UNSC | United Nations Security Council |

| US | United States |

Lists of figures

Figure 1. Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record Elements

Figure 2. Steps in the Air Passenger Targeting

Figure 3. Process for Developing Scenarios for Scenario Based Targeting

Figure 4. What is a “High Risk” Flight or Passenger

Figure 5. Instances Where the Link to Serious Transnational Crime or Terrorism Offences was unclear

Figure 6. Instances Where the Potential Contravention was Unclear in Targets

Figure 7. Legal Tests under the CHRA and the Charter

Figure 8. Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record Data That Relate to Protected Grounds

Figure 9. Instances Where Behavioural Indicators Were Protected Grounds or Did Not Narrow Scope

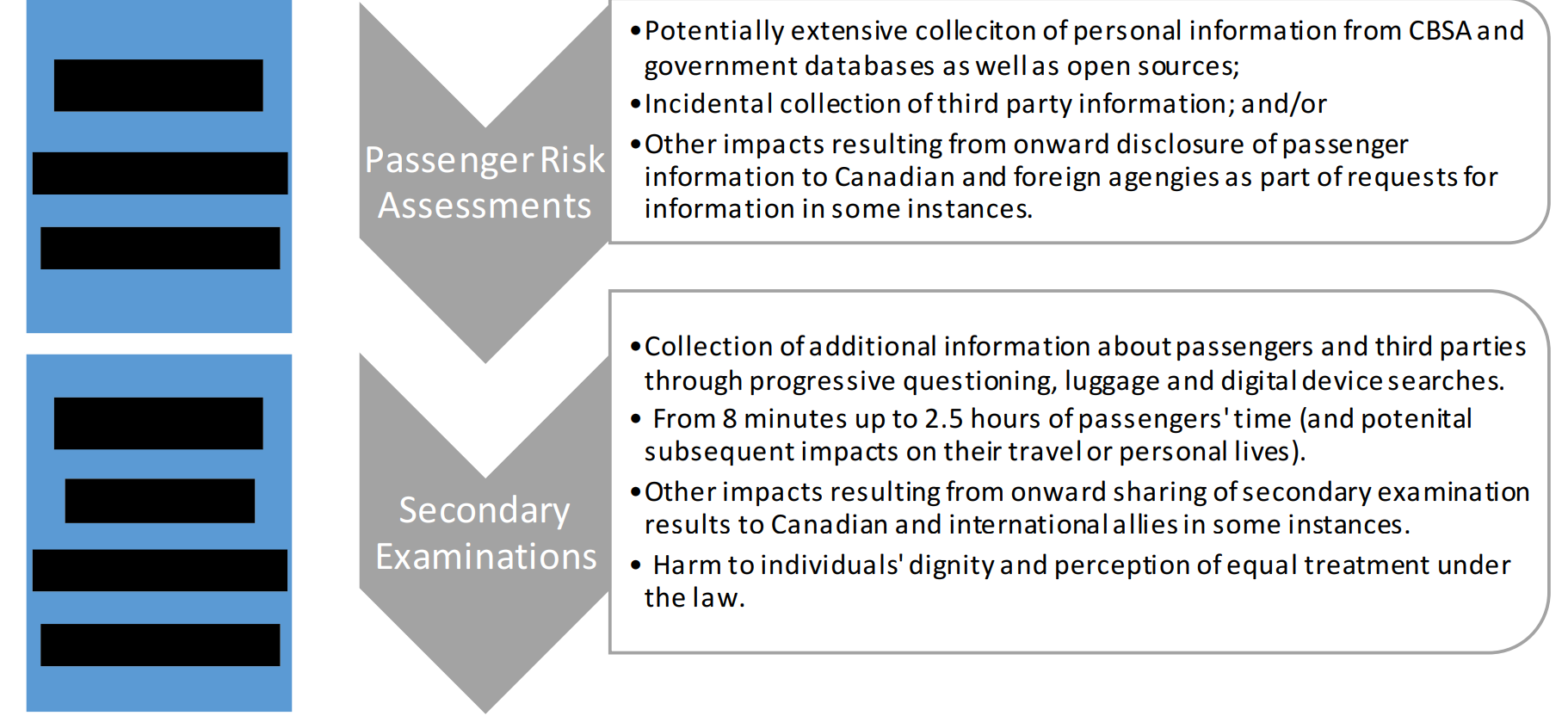

Figure 10. Impacts on Travellers Resulting from Initial Triage

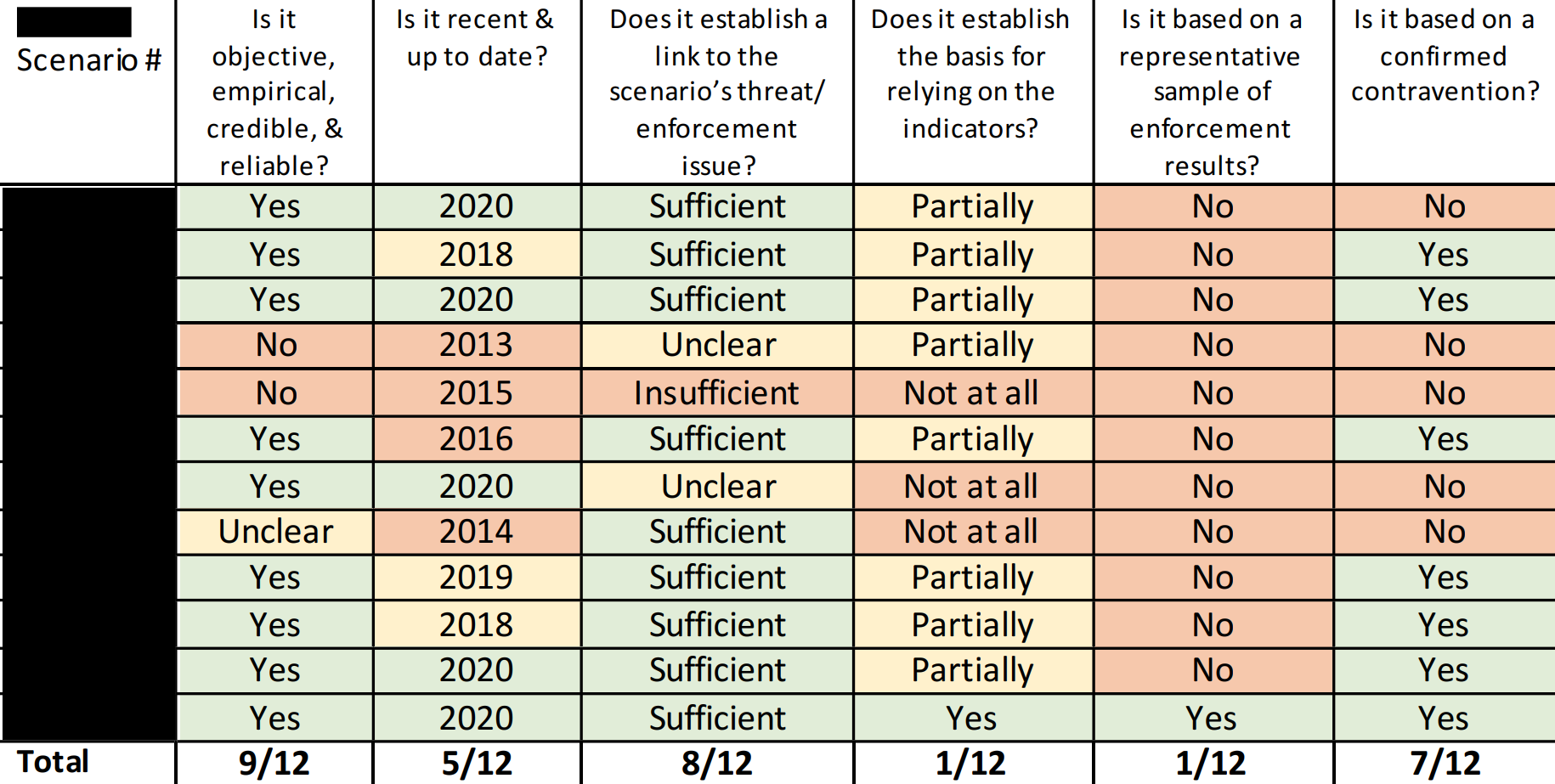

Figure 11. Summary of NSIRA’s Assessment of Scenario Supporting Documentation

Figure 12. Examples of Weaknesses in Scenario Supporting Documentation

Figure 13. Example of a Well-Substantiated Scenario

Figure 14. Why the Justification for the Indicators Used in Targeting is Important

Authorities

The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) conducted this review under paragraph 8(1)(b) of the NSIRA Act.

Introduction

The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)’s Air Passenger Targeting program is one of several programs that help the Agency fulfill its mandate of “providing integrated border services that support [Canada’s] national security and public safety priorities and facilitate the free flow of [admissible] persons and goods” into Canada. Air Passenger Targeting uses passenger data submitted by commercial air carriers called Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data to conduct pre-arrival risk assessments. The pre-arrival risk assessments are intended to identify individuals at higher risk of being inadmissible to Canada or of otherwise contravening the CBSA’s program legislation. In 2019-20, the CBSA received this information to risk assess 33.9 million inbound international travellers.

Air Passenger Targeting has become an increasingly important tool for screening passengers. The CBSA’s deployment of self-serve kiosks to process travellers arriving in Canadian airports has decreased the ability of Border Services Officers to risk assess travellers through in-person observations or interactions, increasing the CBSA’s reliance on pre-arrival risk assessments, like Air Passenger Targeting, to identify and interdict inadmissible people and goods.

The Canadian border context affords the CBSA considerable discretion in how it conducts its activities. Individuals have lower reasonable expectations of privacy at the border. Brief interruptions to passengers’ liberty and freedom of movement are reasonable, given the state’s legitimate interest in screening travellers and regulating entry. However, the activities of the CBSA must not be discriminatory, meaning that any adverse differential treatment on the basis of prohibited grounds of discrimination, such as national or ethnic origin, age, or sex must be justified. Both the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter) create distinct obligations in this regard. The Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data that the CBSA uses to perform these pre-arrival risk assessments includes personal information about passengers that is either a prohibited ground of discrimination or that relates closely to such grounds, warranting further attention to the CBSA’s compliance with these obligations. As Air Passenger Targeting involves passenger screening to identify national security-related risks (among others), attention to the validity of the inferences underpinning the CBSA’s interpretation of passenger information also has implications for Canada’s national security.

Air Passenger Targeting also engages Canada’s international commitments to combat terrorism and serious transnational crime and to respect privacy and human rights in the processing of passenger information. The latter commitment has been of particular importance to the European Union in the context of ongoing negotiations on an updated agreement for sharing passenger information.

About the review

NSIRA’s review examined two main aspects of the lawfulness of the CBSA’s passenger triaging activities in Air Passenger Targeting and their effects on travellers. The review examined whether the CBSA’s triaging activities comply with restrictions established in statutes and regulations on the use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data; and whether passenger triaging activities comply with the CBSA’s obligations pertaining to non-discrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Charter.9 NSIRA expected to find that the CBSA’s triaging activities are conducted with appropriate legal authority and comply with use restrictions on the passenger data and non-discrimination obligations, namely, that any adverse differentiation among travellers based on protected grounds is supported by adequate justification.

The review focused on the CBSA’s triaging activities in Air Passenger Targeting relevant to identifying potential national security-related threats and contraventions. However, it also examined the program as a whole across the CBSA’s three main targeting categories—national security, illicit migration, and contraband—to fully appreciate the program’s governance and operations, given its reliance on intelligence analysis. The review examined the Air Passenger Targeting program as implemented by the CBSA between November 2020 and September 2021.

The review relied on information from the following sources:

- Program documents and legal opinions

- Information provided in response to requests for information (written answers and briefings)

- [***Sentence revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes the number of scenarios that were active on May 26, 2021***]

- Supporting documentation for a sample of 12 scenarios that were active on May 26, 2021

- A sample of 83 targets issued between January and March 2021 (including 59 targets subsequent to Flight List Targeting and 24 targets subsequent to Scenario Based Targeting)

- A live demonstration at the National Targeting Centre, which conducts Air Passenger Targeting

- Open sources, including news articles, academic articles, and prior reviews by other agencies.

- Past performance data and relevant policy developments

Confidence statement

For all reviews, NSIRA seeks to independently verify information it receives. Access to information was through requests for information and briefings by the CBSA. During this review, NSIRA corroborated the information that was received through verbal briefings by receiving copies of program files and alive demonstration of Air Passenger Targeting. NSIRA is confident in the report’s findings and recommendations.

Orientation to the Review Report

After providing essential background information on the steps and activities involved in Air Passenger Targeting and its contribution to the CBSA’s mandate in Section 5, the review’s findings and recommendations are presented in Section 6.

In Section 6.1, NSIRA’s assessed the CBSA’s compliance with statutory and regulatory restrictions on the CBSA’s use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data. Weaknesses in how the CBSA documents its Air Passenger Targeting program activities prevented NSIRA from verifying that all triaging activities complied with these restrictions. These weaknesses also impede the CBSA’s own ability to provide effective internal oversight.

In Section 6.2, NSIRA’s assessed the CBSA’s compliance with its obligations pertaining to nondiscrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Charter. Similar weaknesses in documentation and recordkeeping prevented the CBSA from demonstrating, in several instances, that an adequate justification exists for its reliance on the indicators it created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data to triage inbound travellers. Ensuring that Air Passenger Targeting triaging practices are substantiated by relevant, reliable and documented information and intelligence is important to demonstrating that travellers’ equality rights are being respected, given that some of the indicators relied on to triage passengers relate to protected grounds and given that passenger triage may lead to adverse impacts for travellers. NSIRA recommends a number of measures to improve recordkeeping and identify and mitigate discrimination-related risks.

Background and content

Air Passenger Targeting and the CBSA’s Mandate

The Air Passenger Targeting program is housed within the National Targeting Centre and is currently supported by 92 Full-Time Equivalents. Air Passenger Targeting is one of several targeting programs at the CBSA, and pre-arrival risk assessments are also performed on cargo and conveyances in other modes of travel, such as marine or rail. Pre-arrival risk assessments are currently only performed on crew and passengers for commercial-based air and marine travel. Screening and secondary examinations of travellers entering Canada through other modes of travel such as land or rail are undertaken at the border.

The Air Passenger Targeting pre-arrival risk assessments are intended to help front line Border Services Officers to identify travellers and goods with a higher risk of being inadmissible to Canada or of otherwise contravening the CBSA’s program legislation and referring them for further examination once they arrive at a Canadian Port of Entry.

Pre-arrival risk assessments are performed in relation to multiple enforcement issues, all of which are associated with ever-evolving travel patterns and traveller characteristics that may vary from one part of the world to the other. Staff at the National Targeting Centre receive training, develop on-the-job experience, and have access to a large body of information and intelligence to perform their duties.

How Air Passenger Targeting works

Key Information Relied Upon in Air Passenger Targeting

Air Passenger Targeting relies on two sets of information to triage passengers for these risk assessments. The first set consists of information about passengers that commercial air carriers submit to the CBSA under section 148(1)(d) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and 107.1 of the Customs Act. This information is referred to as Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data. Advance Passenger Information comprises information about a traveller and the flight information associated with their travel to Canada; Passenger Name Record data is not standardized and refers to information about a passenger kept in the air carrier’s reservation system. The particular data elements are prescribed under section 5 of the Passenger Information(Customs) Regulations and section 269(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations.

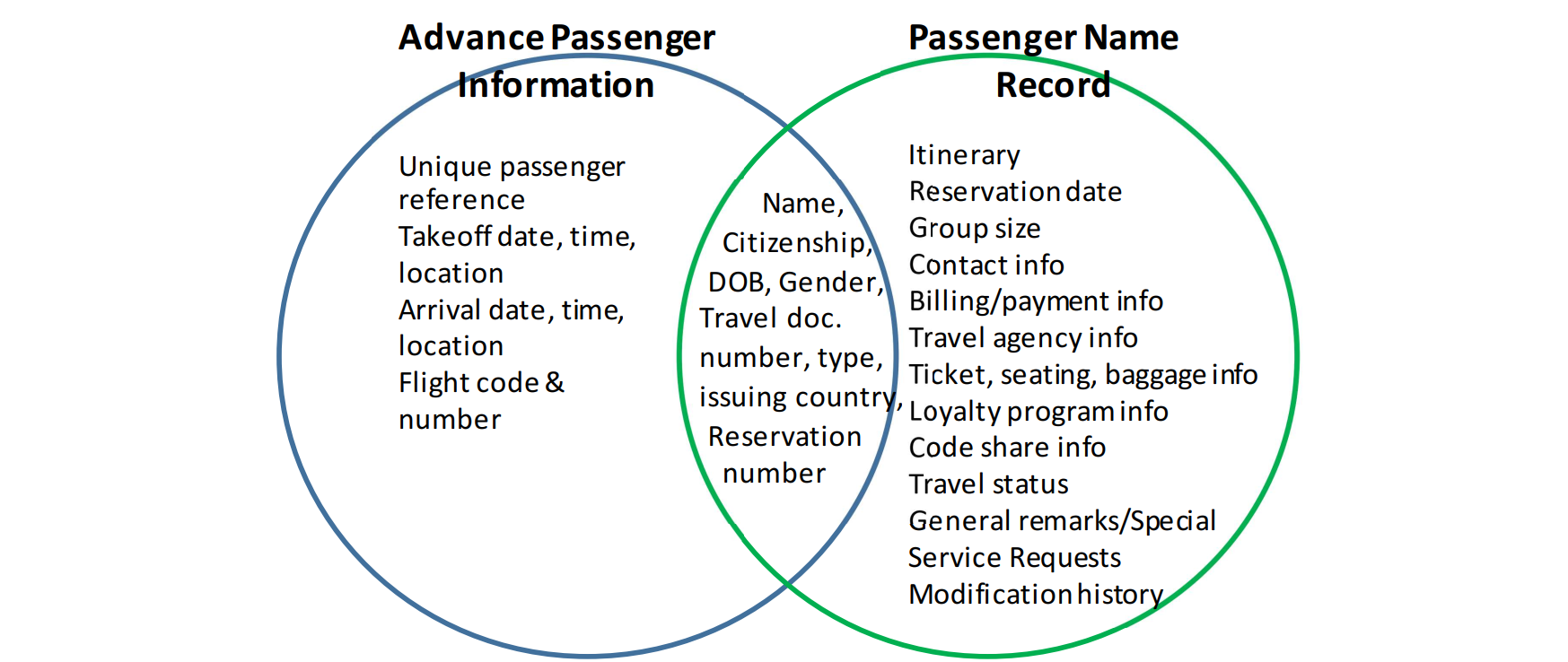

For simplicity, NSIRA refers to Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record Data collectively as “passenger data” in this review unless otherwise specified. Figure 1 provides an overview of common Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data elements. Once received by the CBSA, the passenger data is loaded into the CBSA’s Passenger Information System (PAXIS). This is the main system used to conduct Air Passenger Targeting.

Figure 1. Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record Elements

The second set consists of information and intelligence from a variety of other sources that is used to help the CBSA determine which Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data elements may indicate risks in passengers’ characteristics and travel patterns in the context of specific enforcement issues and can therefore provide indicators for triaging passengers. Key sources include:

- Recent significant interdictions that are cross-referenced with historical enforcement and intelligence information, as well as with the Advance Passenger Information and/or Passenger Name Record data for interdicted subjects

- Port of entry seizures

- Information from Liaison Officers overseas

- International intelligence bulletins

- Intelligence products shared by domestic and international partners concerning actionable indicators and trends from partner agencies based on their area of expertise.

- Open sources, including news articles, op-eds, academic articles, social media.

- CBSA intelligence products based on one or more of the above-mentioned sources, such as Intelligence Bulletins, Targeting Snapshots or Placemats, Country Threat Assessments, Intelligence Briefs, daily news briefings.

The quality of the information supporting the CBSA’s inferences as to who may be a high-risk traveller is important to ensure the triage is reasonable and non-discriminatory (see Section 6.2).

Step by Step Process of Air Passenger Targeting

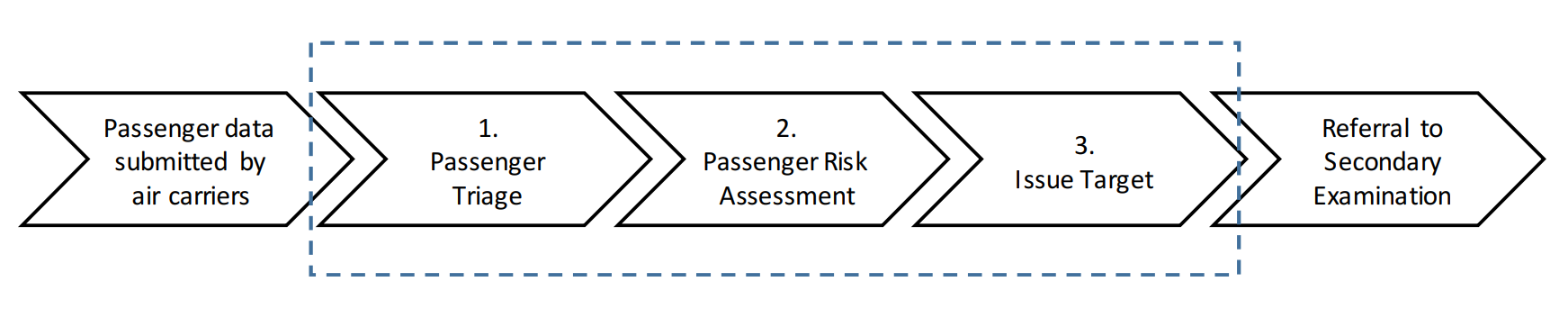

Air Passenger Targeting involves three key steps, illustrated in Figure 2. First, CBSA officers triage passengers based on the Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data using manual or automated methods. Second, CBSA officers undertake a risk assessment of the selected passengers using different sources of information and intelligence. Third, Targeting Officers decide whether to issue a “target,” based on the results of this risk assessment.

Figure 2. Steps in the Air Passenger Targeting Process

Step 1: Passenger Triage

The CBSA uses two distinct methods to triage passengers using Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data: Flight List Targeting and Scenario-Based Targeting.

Flight List Targeting is a manual triage method that involves two main steps. The officers use their judgement to make these selections (see Figure 4 for further details).

- Targeting Officers select an inbound flight from those arriving that day that they consider to be at “higher risk” of transporting passengers that may be contravening the CBSA’s program legislation.

- Targeting Officers then select passengers on those flights for further assessment, based on the details displayed about them in the list of passengers.

Scenario Based Targeting is an automated triage method that relies on “scenarios,” or pre-established set of indicators created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data elements that the CBSA considers as risk factors for a particular enforcement issue. The data for passengers on all inbound flights are automatically compared against the parameters of each scenario. Any passengers whose data match all of the parameters of one (or more) scenario are automatically selected for a Targeting Officer to assess further.

[***Sentence revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes the steps involved in developing scenarios ***]

Figure 3. Process for Developing Scenarios for Scenario Based Targeting

[***Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes the steps involved in developing scenarios. ***]

Both of these triage methods are informed by an analysis of information and intelligence in slightly different ways. In Scenario Based Targeting, the National Targeting Centre’s Targeting Intelligence unit analyses intelligence and information to identify combinations of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data elements associated with “high risk” passengers and travel patterns for the purposes of developing scenarios, as illustrated in Step 1 of Figure 3 above. In Flight List Targeting, Targeting Officers analyze information and intelligence to develop a personal “mental model” about what constitute “high risk” flights or passengers in the context of a specific enforcement issue. Examples are provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4. What is a “High Risk” Flight or Passenger?

Based on information about past trends and intelligence about future travel, CBSA officers identify certain flights or airports that have had a higher incidence of travellers subsequently found to be in contravention of the CBSA’s program legislation. The CBSA assesses flights from these points of origin as “high risk” flights. [Sentence revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It provided examples of flight information that the CBSA indicated was associated with past contraventions.]

Based on similar analysis, CBSA officers have assessed that certain combinations of traveller characteristics and travel patterns are or may be associated with contraventions of the CBSA’s program legislation. Travellers who match these characteristics are considered to be “high risk” travellers. [Sentence revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It provided examples of flight information that the CBSA indicated was associated with past contraventions.]

Steps 2 and 3: Passenger Risk Assessments and Issuing Targets

The initial triage of passengers may result in two additional steps for those who have been selected for further assessment: further passenger risk assessments (referred to by the CBSA as a “comprehensive review”) and a decision to issue a target if risks that were initially identified remain.

The passenger risk assessment process involves requesting and analyzing the following information to determine whether risks initially identified in the passenger’s Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data are no longer of concern (referred to as “negation”), whether they continue to be of concern, or whether those concerns have increased:

- Mandatory and discretionary queries of CBSA and other government databases;

- Open-source searches (including social media);

- Requests for information to other Government of Canada departments and to the United States Customs and Border Protection agency (mandatory for all potential contraventions related to national security, but optional for other enforcement issues).

A target is issued when the risk assessment cannot “negate” risks initially inferred about the passenger. A target is a notification to Border Services Officers at a Canadian Port of Entry (in this case, airports) to refer the passenger for “secondary examination”. It does not mean that a passenger has been found in contravention of the CBSA’s program legislation. A target includes details about the passenger and the risks identified in relation to the potential contravention (referred to as a “target narrative”).

During secondary examinations, Border Services Officers engage in a progressive line of questioning. This questioning is informed by the details contained in the target as well as all other information available to the officers, including information provided by travellers and other observations developed during the examination. This information may allow the officers to establish a reasonable suspicion about whether the passenger has contravened customs, immigration, or other requirements that are enforced by the CBSA and pursue further questioning or examination. These examinations may also involve a search of luggage and/or digital devices where required and with managerial approval. The outcome of these examinations determines the next steps for individual travellers.

Findings and Recommendations

The CBSA’s Compliance with Restrictions Established in Law and Regulations

Restrictions that Apply to Air Passenger Targeting and Why They Matter

While Air Passenger Targeting is not explicitly discussed in legislation, both the Customs Act and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act provide the CBSA with legislative authority to collect and use Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data in Air Passenger Targeting. Such use is further supported by section 4(1)(b) of the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations, which expressly contemplates the use of Passenger Name Record data to conduct trend analysis and to develop risk indicators for the purpose of identifying certain high-risk individuals.

NSIRA is satisfied that these statutory provisions also authorize the CBSA to collect and analyze the information and intelligence necessary to support Air Passenger Targeting. These inputs are necessary to contextualize its interpretation of the Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data and determine which data elements characterize “high risk” passengers and travel patterns in the context of different enforcement issues. However, the review did not examine whether all information and intelligence collected by the CBSA was necessary to the conduct of its operations (in Air Passenger Targeting or otherwise). This related topic may be the subject of future review.

These authorizing provisions create restrictions on the CBSA’s use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data. Two layers of use restrictions apply: one set arises from the Customs Act or the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act as authorizing statutes, and the other set arises from section 4 of the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations.

In examining compliance with the first set, NSIRA referred to section 107(3) of the Customs Act, the broader of the two authorities. Section 107(3) authorizes the CBSA to use Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data:

- To administer or enforce the Customs Act, Customs Tariff, or related legislation;

- To exercise its powers, duties and functions under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, including establishing a person’s identity or determining their inadmissibility; and/or

- For the purposes of its program legislation.

NSIRA also examined compliance with the use restrictions established by section 4 of the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations. The regulations limit the CBSA’s use of Passenger Name Record data to the identification of persons “who have or may have committed” either a terrorism offence or a serious transnational crime. The data can be used to identify such persons directly, or to enable trend analysis or the development of risk indicators for that same purpose.

The Protection of Passenger Information Regulations were enacted to fulfill Canada’s commitments respecting its use of Passenger Name Record data as part of an agreement signed with the European Union. The Agreement specifies that “[Passenger Name Record] data will be used strictly for purposes of preventing and combating: terrorism and related crimes; other serious crimes, including organized crime, that are transnational in nature.” Although the 2006 agreement expired, ongoing efforts to negotiate a new agreement place continued importance on ensuring the CBSA’s ability to demonstrate compliance with the lawful uses of Passenger Name Record data. The constraints established in the regulations also indicate the Minister’s determination of when the use of Passenger Name Record data by the CBSA will be reasonable and proportional.

As a matter of law, the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations restrictions apply only to Passenger Name Record data provided to the CBSA under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. However, Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data are integrated within its systems. The CBSA also uses Passenger Name Record data to issue targets for the purposes of the Customs Act and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act simultaneously. Given the CBSA’s commitments to the European Union under the above-mentioned Agreement and these other considerations, the CBSA observes these regulatory restrictions across its Air Passenger Targeting program as a matter of policy.

Assessing compliance with the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations required NSIRA to determine whether the enforcement issue of interest in the triaging decision fell within the regulations’ definitions of a “terrorism offence” or of a “serious transnational crime.”

What NSIRA found?

NSIRA found that, in its automated Scenario Based Targeting triaging method, the CBSA’s use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data to identify potential threats and contraventions of the CBSA’s program legislation complied with statutory restrictions. For its manual Flight List Targeting triaging method, NSIRA was not able to assess the reasons for the CBSA’s selection of individual travellers and was therefore not able to verify compliance with section 107(3) of the Customs Act. For both methods, NSIRA was also unable to verify that all triaging complied with the regulatory restrictions imposed by the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations on the CBSA’s use of Passenger Name Record data, namely that its use served to identify potential involvement in terrorism offences or serious transnational crimes. This was due to lack of precision in Scenario Based Targeting program documentation and lack of documentation about the basis for Flight List Targeting triaging decisions.

Do Scenario Based Targeting triage practices comply with statutory and regulatory restrictions?

In Scenario Based Targeting, all scenarios complied with the statutory restrictions on the use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data, as all scenarios were developed for the purposes of administering or enforcing the CBSA’s program legislation. However, in several instances, the scenario documentation did not precisely identify why the CBSA considered a particular enforcement concern to be related to a terrorism offence or serious transnational crime. This lack of precision obscured whether the scenarios complied with the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations.

NSIRA reviewed the information contained within the scenario templates for [***Sentence revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes the number of scenarios that were active on May 26, 2021***]. The templates require information on the specific legislative provisions associated with the potential contravention the scenario seeks to identify. The templates also require a general description of the details of the scenario, including the potential contravention.

The CBSA’s use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data in Scenario Based Targeting complied with the first layer of legal restrictions, as all of the scenarios sought to identify contraventions of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, the Customs Act, the Customs Tariff, and/or the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, which are authorized purposes under section 107(3) of the Customs Act. In many instances, the scenario’s purpose also complied with the complementary restrictions under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.

Regarding the second layer of restrictions imposed by the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations, most scenarios cited provisions for potential contraventions that were reasonably viewed as relating to terrorism or serious transnational crime. In several instances, however, the link to terrorism or serious transnational crime was not clear. This occurred in one of two ways:

- Scenarios did not establish why a potential contravention cited as the intent of the scenario was related to an offence punishable by a term of at least four years of imprisonment, which one of the criteria in the definition of a serious transnational crime. It was therefore unclear how the enforcement interest related to a serious transnational crime (observed in at least 28 scenarios).Including more precise details on how the potential contravention relates to a serious transnational crime or terrorism offence would more clearly establish this link.

- Scenarios cited three or more distinct grounds for serious inadmissibility, such as sections 34, 35,36, and/or 37 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act without providing further details as to why all grounds were relevant to the conduct at issue in the scenario (observed in at least 20 scenarios).

This obscured how the grounds related meaningfully to the conduct at issue and why the conduct related to a terrorism offence or serious transnational crime. Including more precise details on how each ground of inadmissibility included in a scenario is relevant to the conduct at issue would help in this regard.

Illustrative examples are provided in Figure 5, and further details on NSIRA’s assessment of compliance with the Customs Act and the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations are provided in Appendix 8.3.

Figure 5. Instances Where the Link to Serious Transnational Crime or Terrorism Offences was unclear

[Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It described two examples where the link to serious transnational crime or terrorism offences was unclear in scenarios.]

Do Flight List Targeting triage practices comply with statutory and regulatory restrictions?

Lack of documentation about why officers selected particular flights or passengers prevented NSIRA from verifying whether Flight List Targeting triaging practices comply with the use restrictions found in the Customs Act or the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations. This lack of documentation also impedes the CBSA’s internal verification that Flight List Targeting triaging complies with these use restrictions.

As Targeting Officers rely on their judgement to triage passengers in Flight List Targeting, record keeping about triaging decisions is important to be able to verify that triaging complies with relevant statutes and regulations and take corrective action as appropriate. Although the National Targeting Centre has a Notebook Policy, which requires officers to “record all information about the officers’ activities,” the National Targeting Policy and the Air Passenger Targeting Standard Operating Procedures do not specify what stages of Air Passenger Targeting need to be documented or what information needs to be recorded at each step. Moreover, the Air Passenger Targeting Standard Operating Procedures, the Target Narrative Guidelines, and the format for issuing targets in the CBSA’s systems do not require officers to include precise details about the potential contravention that motivated their decision to issue a target.

NSIRA was only able to infer why a passenger was first selected for further assessment in Flight List Targeting from the details of targets, even though the explanatory value of analyzing targets for insight about initial triaging is limited. Targets are not issued for all initially selected passengers : only 15 percent of the passengers that were selected for a comprehensive risk assessment led to a target being issued in 2019-20.

As well, the enforcement issue contained within targets may have changed during later stages in the Air Passenger Targeting process and may not necessarily reflect the issue that motivated the initial triaging decision.

NSIRA found that all targets in a sample of 59 targets issued subsequent to Flight List Targeting complied with the first layer of use restrictions under section 107(3) of the Customs Act, as they cited either the “IRPA” or the “Customs Act” in the details of the target. However, the targets did not always specify a particular contravention of these Acts, which created a challenge for determining why the officers’ interest in the passenger related to a terrorism offence or serious transnational crime. Based on other descriptive details about the behaviours or risk factors contained in the target, it was only possible to clearly infer the enforcement issue and determine that it was a terrorism offence or a serious transnational crime in approximately half the targets (29 of 59). Illustrative examples are provided in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Instances Where the Potential Contravention was Unclear in Targets

[***Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It described two examples of targets where the potential was unclear based on the details of the target.***]

Why is precision in record keeping important?

It is important to ensure that the potential contravention at issue is clear in scenario templates and targets and to ensure that recordkeeping about the reasons animating Flight List Targeting triaging is adequate in order to allow effective verification that all triaging activities comply with statutory and regulatory restrictions.

The CBSA’s current oversight functions consist of reviewing new scenarios prior to and in parallel with their activation and of reviewing targets after the fact for quality control and performance measurement. However, the documentation weaknesses identified above prevent the CBSA from ensuring that its triaging activities comply with statutory and regulatory restrictions. The CBSA’s oversight mechanisms should include robust verification that scenarios and manual Flight List Targeting triaging practices are animated by issues relevant to the administration or enforcement of the CBSA’s program legislation. Where Passenger Name Record data is used, oversight should also verify that the enforcement issue constitutes or is indicative of a terrorism offence or serious transnational crime. More precise and consistent recordkeeping of the reasons underlying passenger triage decisions in both Scenario Based Targeting and Flight List Targeting would help in this respect.

Guidance on what the legislative and regulatory restrictions entail for targeting activities was also not clearly articulated in the National Targeting Centre’s policies, standard operating procedures, or training materials. These guidance materials should include further specifics on:

- Which issues pertinent to admissibility under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act or other contraventions of the CBSA’s program legislation constitute or relate to a serious transnational crime or terrorism offence and why; and

- How to document triaging decisions on a consistent basis to enable internal and external verification that targeting activities align with these legal and regulatory restrictions.

For example, the Scenario Based Targeting Governance Framework included helpful examples of risk categories that identify associated legislative provisions. Though the examples align with the definitions of serious transnational crime and terrorism offences in the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations, no explanation linking the examples to alignment with the regulations are provided. Equivalent guidance does not exist for Flight List Targeting.

Clearly identifying the potential enforcement issue is also important to verifying that the indicators created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data that are used to triage passengers are relevant to the issue and reliably predictive of it. This is important for demonstrating that the triaging practices are reasonable and non-discriminatory (see Section 6.3).

Finding 1. The CBSA’s use of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data in Scenario Based Targeting complied with section 107(3) of the Customs Act.

Finding 2. The CBSA does not document its triaging practices in a manner that enables effective verification of whether all triaging decisions comply with statutory and regulatory restrictions.

Recommendation 1. NSIRA recommends that the CBSA document its triaging practices in a manner that enables effective verification of whether all triaging decisions comply with statutory and regulatory restrictions.

The CBSA’s Compliance with Obligations Pertaining to Non-Discrimination

The CBSA’s Non-Discrimination Obligations and Why They Matter

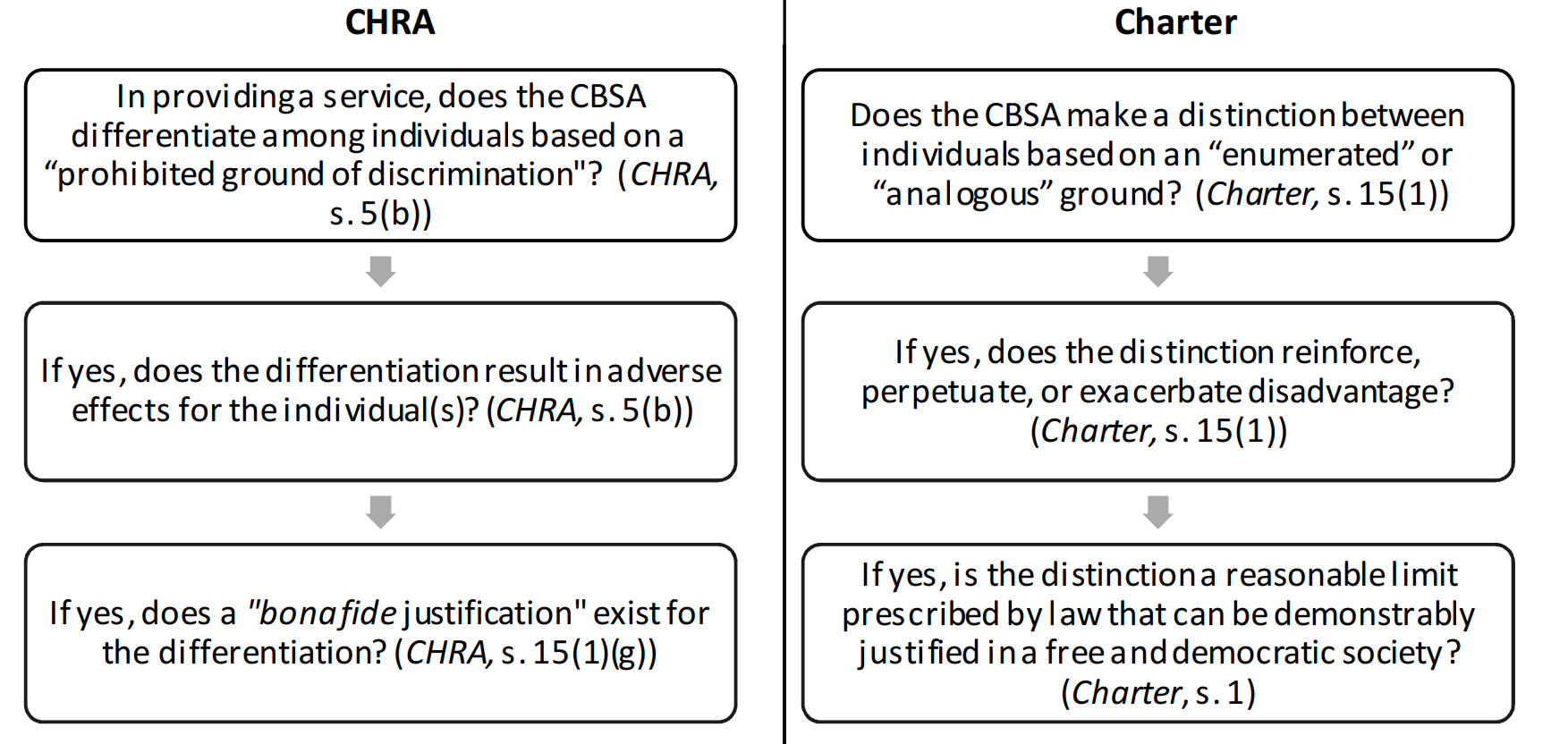

The Canadian Human Rights Act and the Charter each establish obligations pertaining to nondiscrimination. The tests for assessing whether or not discrimination has occurred are thematically similar, though with differences in approach and terminology as illustrated in Figure 7. The analysis under both instruments begins with a factual inquiry into whether a distinction is being drawn between travellers based on prohibited grounds of discrimination, and if so, whether it has an adverse effect on the traveller or reinforces, perpetuates or exacerbates disadvantage. If so, the analysis under the CHRA examines whether there is a bona fide justification for the adverse differentiation. The corresponding analysis under the Charter examines whether the limit on travellers’ equality rights is demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.

Figure 7. Legal Tests under the CHRA and the Charter

What NSIRA Found

Although triaging in Air Passenger Targeting typically relies on multiple indicators that are created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data, some of these indicators are protected grounds or relate closely to protected grounds. Air Passenger Targeting triaging results in impacts on travellers that can be considered adverse in nature and are capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating disadvantages. This creates a risk of prima facie discrimination. While these limits on travellers’ equality rights may be justifiable, weaknesses in the CBSA’s program documentation prevented the CBSA from demonstrating that a bona fide justification supported the adverse differentiation of travellers in several instances. A large body of information and intelligence is available to CBSA staff; however, it was not compiled and documented in a way that consistently established why certain indicators used to triage passengers related to a threat or potential contravention and did not always establish that these indicators were current and reliable. This weakness with respect to ensuring precise, well-substantiated documentation is similar to the one already highlighted in relation to the CBSA’s compliance with legal and regulatory restrictions.

Further information on the nature of the differentiations made in Air Passenger Targeting triaging practices and their impact on individuals would be required to conclusively establish whether or not triaging practices are discriminatory. However, the risk of discrimination is sufficiently apparent to warrant careful attention. In this review, NSIRA will recommend measures that could help the CBSA to assess and mitigate discrimination-related risks.

Does the CBSA make a distinction in relation to “protected grounds”?

Some of the indicators relied on to triage passengers are either protected grounds themselves or relate closely to protected grounds. NSIRA observed instances where passengers appeared to be differentiated based on protected grounds.

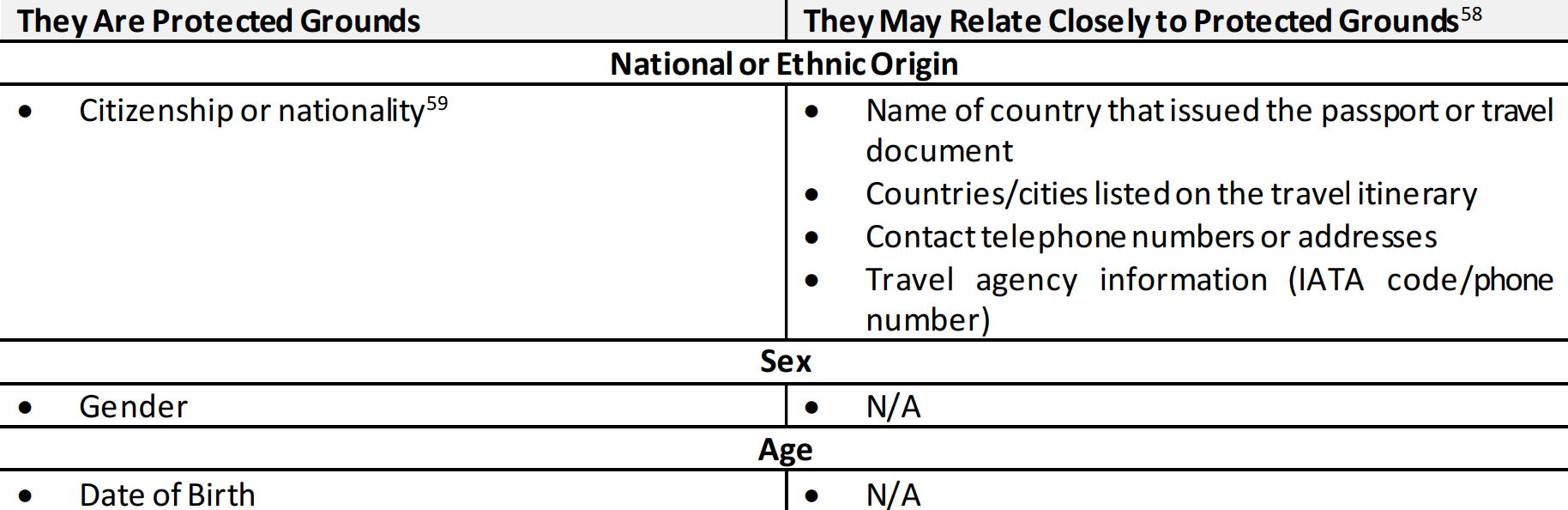

NSIRA examined all scenarios that were active on May 26, 2021 and a sample of targets to determine whether the CBSA’s triaging practices engage prohibited grounds of discrimination, such as age, sex, or national or ethnic origin. NSIRA refers to these as “protected grounds” in the report. The assessment considered:

- How the indicators used to triage passengers relate to protected grounds;

- The significance of the indicators in triage and how individual indicators were weighted in relation to each other; and

- Whether these indicators created distinctions among individuals, or classes of individuals, based on protected grounds, whether in their own right or by virtue of their cumulative impact.

NSIRA found that the CBSA triages passengers based on a combination of indicators that are created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data. This triaging often included indicators that were either protected grounds themselves or related closely to protected grounds. Examples of these indicators are provided in Figure 8 with further details on how the CBSA relied on these indicators in Appendix 8.4.

Figure 8. Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record Data That Relate to Protected Grounds

Although the CBSA took certain measures to mitigate the possibility that triaging decisions were based primarily on protected grounds, NSIRA observed that these measures did not always adequately mitigate that risk. More specifically:

- [***Note revised to remove injurious or privileged information. It lists examples of scenarios that relied on single elements.***] NSIRA observed instances where scenarios continued to rely largely on indicators that related closely to protected grounds. This was because the behavioural indicators were often used in a way that related closely to a protected ground (primarily national origin) or because the parameters for the behavioural indicators were very broad (for example: passports as a travel document) and did not significantly narrow the range of passengers captured by the scenario. Examples are provided in Figure 9.

- Scenario Based Targeting triaging for potential contraventions relevant to national security focused disproportionately on a certain profile of passengers: [***Sentence revised to remove injurious or privileged information. It described a combination of traveller characteristics that relates to protected grounds.***] While individual scenarios considered a variety of other indicators that differed between each scenario and that appeared to be specific to a unique set of personal characteristics and behavioural patterns for each national security risk, the overall effect of the scenarios created a differential impact largely focused on this particular profile.

Figure 9. Instances Where Behavioural Indicators Were Protected Grounds or Did Not Narrow Scope

[***Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes two examples of scenarios where behavioural indicators were used in a way that related closely to a protected ground or because the parameters for the behavioural indicators were very broad and did not significantly narrow the range of passengers captured by the scenario***]

As the CBSA’s triaging practices engage protected grounds and resulted in a differentiation of passengers based on protected grounds in certain instances, NSIRA considered the impacts that these distinctions may produce.

Do distinctions result in adverse impacts capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating a disadvantage?

Distinctions made in passenger triage lead to several types of potential impacts for the passengers that are selected for further assessment. These impacts are adverse in nature and are capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating disadvantages.

NSIRA considered the kinds of impacts that Air Passenger Targeting has for the passengers who are selected for further assessment through the initial triage. These impacts are illustrated in Figure 10. Each may have important effects on passengers’ time, privacy, and equality, particularly as the impacts accumulate during the screening process and/or where these impacts are experienced repeatedly by the same travellers.

Figure 10. Impacts on Travellers Resulting from Initial Triage

[Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes numbers of passengers targeted by year.]

These impacts can be adverse in nature and are reasonably understood as being capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating disadvantage, particularly when viewed in light of possible systemic or historical disadvantages. However, disaggregated data on the ethno-cultural, gender, or other group identity of affected passengers and their circumstances in Canadian society would be required to fully appreciate Air Passenger Targeting’s impacts on affected groups.

A risk of prima facie discrimination is established where these adverse impacts accrue to individuals based on protected grounds. These adverse impacts on protected groups will not amount to discrimination under the Canadian Human Rights Act if the CBSA can demonstrate a bona fide justification for the differentiation and will be allowed under the Charter if the CBSA can establish that the distinctions are a reasonable limit on travellers’ equality rights.

Does the CBSA have an adequate justification for the adverse differentiation?

While a large body of information and intelligence is available to CBSA’s staff for their triaging activities, weaknesses in recordkeeping, in the coherent synthesis of this information, and in data collection prevented the CBSA from demonstrating, that an adequate justification exists for its use of the indicators it created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data in several instances.

NSIRA examined how the CBSA relied on information and intelligence to support its triaging practices by reviewing a sample of 12 scenarios and a sample of 59 targets issued subsequent to manual triaging in Flight List Targeting. NSIRA also examined performance data for the selected scenarios. In examining the supporting documentation provided for each scenario demonstrated an adequate justification for the indicators created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data to triage passengers, NSIRA considered a number of factors:

- Whether the information was objective and empirical;

- Whether it was credible and reliable, in terms of its source and the quality of its substantiation;

- Whether the information was recent and up to date;

- Whether the information established a meaningful connection between the indicator(s) and the enforcement issue;

- Whether the indicators were specifically indicative of the enforcement issue or were general;

- Whether the indicators were based on a representative sample size; and

- Whether the reliance on the particular indicators to triage passengers was effective in identifying potential contraventions in the past (i.e. whether empirical results support the reliance).

In Scenario Based Targeting, 11 out of the 12 scenarios in the sample reviewed did not provide an adequate justification for the triaging indicators, due in part to weaknesses in the supporting documentation for scenarios.

A summary of NSIRA’s assessment in relation to each of the assessment criteria is provided in Figure 11 and examples are described below.

Figure 11. Summary of NSIRA’s Assessment of Scenario Supporting Documentation

Most of the supporting documentation for the scenario sample was based on empirical information about enforcement actions or other intelligence products developed by the CBSA or its partners that were derived from clearly identified empirical sources. NSIRA considered these products to be objective and reliable sources. However, NSIRA noted three instances where it was unclear what the basis of the information was, and therefore whether it was objective and credible.

Inconsistencies in how supporting documentation for scenarios was maintained created further challenges for verifying that scenarios were based on reliable and up-to-date information, as four of the scenarios examined relied on information that was more than five years old and the CBSA could not locate one or more documents cited as supporting documentation in nine of the scenarios. While deleting older information is appropriate if it is replaced with more recent information, doing so in absence of more recent supporting information may undermine the CBSA’s the ability to justify the basis of the scenario.

In 3 of 12 scenarios examined, it was unclear how the supporting documentation related to the potential contravention identified in the scenario, which prevented further analysis as to how the indicators created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data were meaningfully connected to the enforcement issue. In all except one of the 12 scenarios, the supporting documentation did not mention one or more of the indicators in the scenario, making it unclear what the basis was for relying on those indicators. A number of the unsubstantiated indicators in those scenarios related closely to protected grounds. Two examples are provided in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Examples of Weaknesses in Scenario Supporting Documentation

[***Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes issues observed in the supporting documentation for two scenarios as examples. These concerned the reliability of speculative claims made in an op-ed that was used as supporting documentation for one scenario that did not provide a clear basis for the indicators relied on in the scenario, and lack of information related to one or more of the indicators in the other scenario.***]

In 11 of the 12 scenarios, the supporting documentation did not include enough information to assess whether the indicators in the scenarios were based on a representative sample size of passengers. This prevented verification that the indicators in the scenario and their parameters reflect a pattern or trend in traveller characteristics and travel patterns rather than a single instance or handful of instances. Deriving indicators from too small a sample size also creates a risk that the indicators are not reliably associated to a potential contravention but rather simply connoted individuals who happen to have been the subject of past enforcement activity. A small sample size can also create bias and confirmation bias about stereotypes pertaining to traveller behaviour or personal characteristics.

Lack of information in 11 of the 12 scenarios on the likelihood and impact of the risk posed by the enforcement issue also prevented further assessment of the extent that the indicators and parameters were unique to the particular enforcement issue either individually or collectively. Moreover, in 4 of the 12 scenarios, the supporting documentation did not include any information to indicate that the indicators and parameters of the scenario had indeed been associated with a confirmed contravention of the CBSA’s program legislation or whether the association between the indicators and the enforcement issue was simply hypothetical. While reliable intelligence could also provide an empirical basis for passenger triage to inform the development of scenarios, information about whether scenarios have actually resulted in confirmed contraventions of the CBSA’s program legislation can be integrated into the supporting documentation of scenarios over time. This issue is examined further in relation to performance data below.

Only one of the 12 scenarios in the sample had enough information to get a sense of the enforcement issue, to understand the basis for relying on the particular indicators in the scenario in relation to the enforcement issue, and to establish that the indicators were based on a clear pattern of association with a large number of confirmed contraventions and reflected an appropriate range. Details about this scenario and why the supporting document substantiated the scenario are provided in Figure 13.

[***Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It describes how the supporting documentation provided for a scenario was based on credible, empirical information that helped to establish the enforcement issue, provided a sense of the prevalence of the issue and its pertinence to the CBSA mandate, established a correlation between the specific indicators in the scenario and confirmed contraventions based on a significant sample size, and established that the parameters for each indicator were appropriately defined.***]

A large body of information and intelligence is available to CBSA staff to inform their targeting activities; however, in all except one of the scenarios, the information, intelligence, and other analytical insights were not brought together coherently to demonstrate that the basis for triaging was justified in those particular instances. The CBSA indicated that they intend to prepare standardized intelligence products that would coherently bring together this information to support the development of new scenarios. Developing such products for all active scenarios would help ensure that an adequate justification exists for all differentiation arising from triaging decisions in Air Passenger Targeting. This issue is examined further in relation to oversight practices below.

In Flight List Targeting, there was insufficient documentation to explain why particular indicators were considered valid risk factors in the context of a particular enforcement issue.

While a large body of information and intelligence exists for Targeting Officers to draw from when triaging passengers in Flight List Targeting, these sources are not necessarily documented in the course of making triaging decisions. Flight List Targeting strategies are not codified and triaging decisions are not consistently documented. This means that the sources and considerations that informed individual triaging decisions were not always apparent in the program documentation that NSIRA reviewed.

Noting the limitations of analyzing targets for insight into initial triaging decisions mentioned previously, the sparse details contained within the sample of 59 targets issued subsequent to Flight List Targeting further limited NSIRA’s assessment. Most of the targets included information specific to each passenger that was obtained through the passenger risk assessment, which reasonably supported a justification for issuing the target. However, this information would have been obtained after initial triaging decisions. Targets occasionally included a brief explanation about why certain elements of Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data were considered to be risk factors, suggesting that the Targeting Officer’s triage decision may have been informed by information and intelligence. However, it was often unclear why the passenger data cited as risk factors in the target suggested a threat or potential contravention of the CBSA’s program legislation. Assessing how the passenger data cited as risk factors in a target corresponded with the potential contravention was further complicated where the enforcement issue was also unclear. Examples in Figure 14 illustrate this challenge.

Figure 14. Why the Justification for the Indicators Used in Targeting is Important

[***Figure revised to remove privileged or injurious information. It returns to the examples of targets discussed in Figure 6 where ambiguity about the enforcement issue created further challenges for assessing how the passenger data cited as risk factors in the target corresponded with the enforcement issue.***]

Performance data for the scenario sample indicates that the indicators created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data to triage passengers may not be closely correlated with the particular enforcement issue.

The CBSA should be able to demonstrate at the outset that information and intelligence justify the use of particular indicators created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data to triage passengers for potential contraventions, particularly where those indicators relate to protected grounds. However, secondary examination results from previously issued targets can provide a source of such information. These results also provide important insight into how strongly certain indicators correlate with potential contraventions and indicate areas where inferences should be revisited and revised.

NSIRA’s analysis of the performance data for the sample of 12 scenarios revealed that the indicators may not necessarily be closely correlated with the particular enforcement issue(s) in the scenarios or predict potential contraventions of the CBSA’s program legislation with high accuracy.

- In many of the scenarios, less than 5 percent of passengers that matched to the scenario—based on their Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data—resulted in an enforcement action or relevant intelligence at the end of a secondary examination, which the CBSA refers to as a “resultant” target. This is due in part to the fact that the vast majority of passengers who are risk assessed do not result in a decision to issue a target. Additionally, certain enforcement issues may have a low probability of occurring, but a high impact. However, the fact that most passengers who match to a scenario are not of concern raises questions about the accuracy of relying on Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data elements as indicators and about the proportionality of the targeting practices.

- On average, a quarter of targets issued (through both Flight List Targeting and Scenario Based Targeting) led to a “resultant” secondary examination, though the scenarios in the sample ranged widely from as low as 4.8 percent to as high as 72.7 percent.

- Only nine of the 12 scenarios led to at least one enforcement action or useful intelligence between 2019-20 or 2020-21. Again, this is not necessarily an issue if an enforcement issue has a low probability of occurring, but a high impact. However, it also raises questions about the empirical basis of the scenario.

- Many of the scenarios led to examination results for issues other than the one that justified the initial targeting. This suggests that the indicators may not be very precise and raises questions about the underlying assumptions or inferences.

NSIRA also observed that the performance data for scenarios matched to a significantly higher proportion of travellers and yielded a higher proportion of “resultant” targets in one year, with much lower results in the next year, indicating how rapidly travel patterns may change. The CBSA indicated that COVID-19 resulted in major shift in travel and business patterns, which has presented challenges for the CBSA to understand how the indicators have evolved in relation to a diversity of enforcement issues and to adapt their targeting strategies. This emphasizes the importance of ensuring that scenarios and Flight List Targeting activities are supported by up-to-date information and intelligence. It also emphasizes the importance of analyzing performance data to rigorously to evaluate, refine, and/or deactivate scenarios in order to remain consistent with a changing risk environment.

However, the insights that can be drawn from the performance data are limited, because the CSBA does not track the results of secondary examinations arising from random referrals or instances where passengers that were not targeted were later found to have contravened the CBSA’s program legislation by other means. This prevents contextualization of Air Passenger Targeting performance against a baseline (namely, whether Air Passenger Targeting is better, on par with, or less effective at predicting a potential contravention of its program legislation than a random referral). Beyond its relevance for performance measurement, baseline data would help to protect the CBSA against confirmation biases where enforcement results in a few isolated cases may reinforce stereotypes even though they do not represent a meaningful trend. Moreover, a “resultant” secondary examination according to the National Targeting Centre’s definition does not necessarily indicate a confirmed instance of non-compliance. This makes it difficult to analyze performance data as source of empirical information to support the CBSA’s justification for using certain indicators to triage passengers, as a “resultant” search may not always signify a correlation between the indicators and the potential contravention.

In sum, the CBSA was not able to demonstrate that adequate justification consistently supported its use of particular indicators in the scenarios and targets examined by NSIRA. This creates a risk that the triaging activities were discriminatory. To avoid discrimination, the link between the indicators used to triage passengers and the potential threats and contraventions they purport to identify must be well-substantiated by recent, reliable, and documented intelligence or empirical information that demonstrates that the indicators are reasonably predictive of potential harms to Canada’s national security and public safety. The CBSA was able to document an adequate justification for passenger triaging in one scenario. Compiling relevant information and intelligence for its other triaging activities would assist in demonstrating that they are also non-discriminatory.

Are any triage-related distinctions that are capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating disadvantage a reasonable limit on travellers’ equality rights?

Further information would be required to determine if any distinctions arising from Air Passenger Targeting that are capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating a disadvantage constitute a reasonable limit on travellers’ equality rights.

The analysis above establishes that Air Passenger Targeting may infringe travellers’ equality rights under the Charter. All Charter rights are subject to reasonable limits, however. To establish that a limit is reasonable, the state must demonstrate that it is rationally connected to a pressing and substantial objective, that it is minimally impairing of the right, and that there is a proportionality between its salutary and deleterious effects. These limits must also be prescribed by law.

The analysis of whether state actions constitute a reasonable limitation of Charter rights is highly fact specific. To examine this question, further data would be required on:

- Precisely how various indicators relate to protected grounds;

- Whether the indicators effectively further national security and public safety;

- The reasonable availability of other means to ensure similar security outcomes at the border;

- The impacts of Air Passenger Targeting for affected passengers; and

- The significance of the contribution of Air Passenger Targeting to national security and other government objectives.

NSIRA notes these data gaps may create challenges for the CBSA in establishing that any discrimination resulting from Air Passenger Targeting is demonstrably justified under section 1 of the Charter. Documenting the contribution of Air Passenger Targeting to national security and public safety, the breadth and nature of its impacts, and contrasting the effectiveness of Air Passenger Targeting relative to other less intrusive means of achieving the CBSA’s objectives would assist the CBSA in demonstrating that the program is reasonable and demonstrably justified in Canadian society.

Has the CBSA complied with its obligations pertaining to non-discrimination?

Air Passenger Targeting triaging practices create a risk of prima facie discrimination. This is due to two key features. First, Air Passenger Targeting relies, in part, on indicators created from Advance Passenger Information and Passenger Name Record data that are either protected grounds themselves or that relate closely to such grounds. This was particularly the case for indicators relating to passengers’ age, sex, and national or ethnic origin. Passengers were differentiated based on these grounds, as they were selected for further assessment due in part to these characteristics. NSIRA also observed that the triaging resulted in disproportionate attention to certain nationalities and sexes, when the cumulative effect of scenarios was taken into account.

Second, this differentiation has adverse effects on travellers. Air Passenger Targeting triaging affects individuals’ privacy through subsequent risk assessments and mandatory referrals for secondary examination. Such scrutiny may also erode an individual’s sense of receiving the equal protection of the law, particularly where these impacts are repeatedly experienced by the same traveller or are perceived to be animated by racial, religious, ethnic, or other biases. These impacts are also capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating disadvantage, especially when viewed in light of systemic or historical disadvantage.

To comply with its obligations under the Canadian Human Rights Act, the CBSA must be able to demonstrate that a bona fide justification exists for this adverse differentiation. However, the CBSA was not able to demonstrate that its choice of indicators was consistently based on recent, reliable, and documented intelligence or empirical information. This weaknesses in the link between the indicators and the potential threats or contraventions they seek to identify, creates a risk of discrimination.

To comply with its Charter obligations, the CBSA must also be able to demonstrate that any resulting discrimination is a reasonable limit on travellers’ equality rights. The same weaknesses NSIRA observed in the CBSA’s substantiation of the link between particular indicators and potential threats or contraventions they seek to identify also undermines its ability to demonstrate the rational connection between its triaging indicators and potential contraventions of its program legislation. Further information on the contribution of Air Passenger Targeting to national security and its relative value compared to other screening means would also be needed to determine whether Air Passenger Targeting can be justified as a reasonable limit under the Charter.

The weaknesses NSIRA observed stem partly from lack of precision in the CBSA’s program documentation and other recordkeeping issues. These are examined in the following section.

Finding 3. The CBSA has not consistently demonstrated that an adequate justification exists for its Air Passenger Targeting triaging practices. This weakness in the link between the indicators used to triage passengers and the potential threats or contraventions they seek to identify creates a risk that Air Passenger Targeting triaging practices may be discriminatory.

Recommendation 2. NSIRA recommends that the CBSA ensure, in an ongoing manner, that its triaging practices are based on information and/or intelligence that justifies the use of each indicator. This justification should be well-documented to enable effective internal and external verification of whether the CBSA’s triaging practices comply with its non-discrimination obligations.

Recommendation 3. NSIRA recommends that the CBSA ensure that any Air Passenger Targeting-related distinctions on protected grounds that are capable of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacerbating a disadvantage constitute a reasonable limit on travellers’ equality rights under the Charter.

What measures are in place to mitigate the risk of discrimination?

The policies, procedures, and training materials reviewed did not adequately equip CBSA staff to identify potential discrimination or to mitigate related risks in the exercise of their duties.

The CBSA’s Air Passenger Targeting policies acknowledged responsibility to respect privacy, human rights, and civil liberties. However, policies, procedures, and training were insufficiently detailed to equip staff to identify and mitigate discrimination-related risks in the exercise of their duties.

- Targeting Officers did not receive any specific training related to human rights.

- The CBSA’s policies, procedures, and other program guidance were not precise enough on specific requirements or steps to equip staff to mitigate risks related to discrimination. In particular, details were lacking in how to associate supporting documentation to a scenario or a triaging decision in Flight List Targeting, and when and how to revisit and update that information on are gular basis.

- No specific policies, procedures, or guidelines were developed for Flight List Targeting beyond the Air Passenger Targeting Standard Operating Procedures, particularly those that relate to record keeping.

The oversight structures and practices that were reviewed were not rigorous enough to identify and mitigate potential discrimination-risks, compounded by an absence of relevant data for this task.

While the CBSA has oversight structures and practices in place for Air Passenger Targeting, it was unclear how these oversight practices were performed. NSIRA identified several areas where they may not be rigorous enough to identify and mitigate potential risks of discrimination as appropriate.

- Scenarios are reviewed for policy, legal, privacy, human rights, and civil liberties implications as part of their activation and on an ongoing basis. However, it is not clear that these oversight functions are guided by a clear understanding of what constitutes discrimination or that all relevant aspects of scenarios are examined.

- Scenarios are reviewed individually on a regular basis. However, it is not clear that the collective impact of the CBSA’s targeting activities is also assessed on a regular basis.

- It is not clear whether any oversight functions related to non-discrimination take place in Flight List Targeting.

Moreover, the CBSA does not gather data relevant to fully assess whether Air Passenger Targeting results in discrimination or to mitigate its impacts.

- The CBSA does not gather disaggregated demographic data about the passengers affected by each stage of the Air Passenger Targeting program. This is relevant to detecting whether the program may be drawing distinctions on protected grounds and/or whether it has a disproportionate impact on members of protected groups.

- The CBSA does not compare information about its triaging practices against information relevant to understanding their potential impacts on travellers and whether those impacts indicate an issue with the CBSA’s targeting practices. This includes information about whether complaints about alleged discrimination at the border relate to a person identified through Air Passenger Targeting and whether the nature of secondary examinations resulting from Air Passenger Targeting may differ from those caused by random or other referrals.

- The CBSA does not gather or assess relevant performance data or data on its impacts against a baseline comparator group in order to contextualize its analysis of this information.

Finding 4. The CBSA’s policies, procedures, and training are insufficiently detailed to adequately equip CBSA staff to identify potential discrimination-related risks and to take appropriate action to mitigate these risks in the exercise of their duties.

Finding 5. The CBSA’s oversight structures and practices are not rigorous enough to identify and mitigate potential discrimination-related risks, as appropriate. This is compounded by a lack of collection and assessment of relevant data.

A number of adjustments to current policies, procedures, guidance, training, and other oversight practices for the Air Passenger Targeting program will help the CBSA mitigate discrimination-related risks by ensuring that distinctions drawn in the initial triage of passengers are based on adequate justifications that are supported by intelligence and/or empirical information. A more detailed treatment on discrimination in training, policies, guidance materials, and oversight for the Air Passenger Targeting program could also provide CSBA staff and the units and committees that perform internal oversight functions with information they may require to exercise their functions accordingly. Careful attention should be paid to the following:

- Understanding the CBSA’s human rights obligations and how risks related to discrimination should be identified and assessed;

- Identifying when triaging indicators may relate to protected grounds;

- Ensuring that any adverse differentiation is based on a well-substantiated connection between the indicators and the potential threat or potential contravention;

- Ensuring the triage of travellers is informed by recent and reliable information and intelligence, with training on how to assess whether the supporting documents meets these requirements;

- Identifying and addressing impacts resulting from passenger triaging practices to ensure that they are minimized and proportional to the benefit gained for public safety or national security;

- Ensuring that impacts resulting from Air Passenger Targeting do not unduly reinforce, perpetuate, or exacerbate disadvantage; and

- Developing tools to detect and mitigate potential biases by gathering and assessing relevant data on targeting practices, their performance, and their impacts.