Backgrounder

Ottawa, Ontario, October 30, 2023 – The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency’s (NSIRA) fourth annual report was tabled in Parliament on October 30, 2023.

This report provides an overview and discussion of NSIRA’s activities throughout 2022, including our findings and recommendations. Our growth and evolution as an agency, including our continued efforts to refine our approaches and processes, both in our reviews and investigations, allowed us to take on new and challenging work. The report also assesses our review work to date, highlighting important themes and trends that have emerged.

Our report summarizes review and investigations work during the 2022 period and highlights our continued effort to enhance transparency by evaluating important aspects of our engagement with reviewed departments and agencies. Review highlights in the report include the following:

- The annual review of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service’s (CSIS) threat reduction measures (TRMs), and the annual review of CSIS’s activities to inform our report to the Minister of Public Safety;

- Reviews of the Communications Security Establishment’s (CSE) active and defensive cyber operations, a foreign intelligence collection program, as well as the annual review of CSE activities to inform our report to the Minister of National Defence;

- A review submitted to the Minister of National Defence under s. 35 of the NSIRA Act on particular human source handling activities undertaken by the Canadian Armed Forces that may not have been in compliance with the law;

- A review of the Canada Border Services Agency’s Air Passenger Targeting program; and

- Our mandated multi-departmental reviews with respect to the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act and sharing of information within the federal government under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act.

During 2022, NSIRA continued modernizing its complaints investigations process, which helped us improve the consistency and efficiency of our work. While the pandemic continued to impact the investigative landscape, processes introduced will reduce delays moving forward. In addition to its other investigations work, NSIRA completed its investigation in relation to a group of 58 complaints referred by the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

This annual report also highlights how the organization pursued greater engagement with partners, seeking and sharing best practices with like-minded review and oversight bodies. In addition, it discusses our organization’s corporate initiatives, including efforts to increase our capacity across our business lines, including technology and information management.

NSIRA’s Members continue to be proud of the work of NSIRA’s Secretariat and the dedication and professionalism of its staff.

Date of Publishing:

Dear Prime Minister,

On behalf of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency, it is my pleasure to present you with our third annual report. Consistent with subsection 38(1) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act, the report includes information about our activities in 2021, as well as our findings and recommendations.

In accordance with paragraph 52(1)(b) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act, our report was prepared after consultation with relevant deputy heads, in an effort to ensure that it does not contain information the disclosure of which would be injurious to national security, national defence or international relations, or is information that is subject to solicitor-client privilege, the professional secrecy of advocates and notaries, or to litigation privilege.

Yours sincerely,

The Honourable Marie Deschamps, C.C.

Chair // National Security and Intelligence Review Agency

Message from the members

As we reflect on this past year’s work, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) is proud of what it has accomplished. We pushed past the challenges of the pandemic and pursued our mission with renewed energy and innovation, understanding that we can adapt and even thrive in this new environment. In 2022, our agency focused on building out and refining its processes as we empowered our review and complaints professionals in their work. These efforts enhanced our ability to meet the challenges of our review and investigations mandates, and thereby improve the transparency and accountability of the national security and intelligence activities across the federal government.

In addition to completing a wide array of reviews and investigations, we have stepped back to reflect on our work and activities over the first few years of our mandate. Despite being a relatively new agency, we are now in the position to make broader observations on the themes and trends in our work, and on the community we review. Indeed, as our experience grows, our approaches in our reviews and investigations mature and evolve. We meet our goals of increased efficiency and expertise through a commitment to address the challenges we face, and by seeking out best practices through expanded partnerships with like-minded domestic and international institutions.

During NSIRA’s brief history, ministers of the Crown have referred certain matters to us for review, as provided for in the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act. At the time of writing, we are in the process of such a referral. As this important review progresses, we will ensure that our commitment to independent and professional review is reflected in all our activities.

This report continues themes from previous annual reports by presenting an overview of our work, a discussion on our engagement with reviewees, and an account of the initiatives we undertook to ensure that our products are complete, thorough and professional. It is our belief that as we grow, we bring confidence to the Canadian public with each review and investigation we conduct.

We would like to thank our previous members, Ian Holloway and Faisal Mirza, for their commitment and contribution to advancing the important work of NSIRA during their tenure, and we wish them well in their future endeavours. Finally, we thank the staff of NSIRA’s Secretariat for their professionalism and dedication to fulfilling the agency’s mandate, and we have no doubt that the year ahead will bring further success for NSIRA

Marie Deschamps

Craig Forcese

Ian Holloway

Faisal Mirza

Marie-Lucie Morin

Executive Summary

In 2022, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) continued to execute its review and investigations mandates with the goal of improving national security and intelligence accountability and transparency in Canada. This related not only to the activities of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), but also to other federal departments and agencies engaged in such activities, including:

- the Department of National Defence (DND) and the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF);

- the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA); and

- all departments and agencies engaging in national security or intelligence activities in the context of NSIRA’s yearly reviews of the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act and the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act.

NSIRA has reflected on its work to date and found that a horizontal view of all its findings and recommendations over the past three years reveals the emergence of three major themes: governance; propriety; and information management and sharing. NSIRA observes that there is an interconnected and overlapping aspect to these issues, and as a result believes that improvements to governance could result in broader improvements across all themes.

Reviews

Canadian Security Intelligence Service

The following are highlights of the reviews completed in 2022 along with key outcomes. The number of reviews defined as completed does not include any ongoing reviews, or reviews completed in previous years but that went through or are in the process of going through consultations for their release to the public. Annex C lists all the findings and recommendations associated with reviews completed in 2022, along with the corresponding responses from reviewees, if provided.

In addition to the reviews discussed below, NSIRA determined that a number of ongoing reviews would be closed or terminated. These decisions, based on a variety of considerations, allow NSIRA to redirect its efforts and resources towards other important issues.

Canadian Security Intelligence Service

In 2022, NSIRA completed the following reviews on CSIS activities:

- the third annual review of CSIS’s threat reduction measures, which provided an overview of all such measures conducted in 2021, and also focused on a subset of these measures to consider the implementation of each measure, how what happened aligned with what was originally proposed, and, relatedly, the role of legal risk; and

- an annual review of CSIS’s activities, which informed, in part, NSIRA’s 2022 annual report to the Minister of Public Safety.

Communications Security Establishment

In 2022, NSIRA completed two dedicated reviews of CSE, and commenced an annual review of CSE activities:

- a review of CSE’s active and defensive cyber operations (ACO/DCO), which is a continuation of NSIRA’s 2021 review of the governance of ACO/DCO by CSE and Global Affairs Canada;

- a review of a sensitive CSE foreign intelligence collection program, which assistedNSIRA in better informing the Minister of National Defence about CSE’s activities; and

- an annual review of CSE activities similar to that for CSIS, begun for the first time in 2022 and that informed, in part, NSIRA’s 2022 annual report to the Minister of National Defence.

Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces

In the course of a review of the Department of National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces (DND/CAF) human source handling activities, NSIRA issued to the Minister of National Defence a report on December 9, 2022, under section 35 of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act in relation to a specific operation. Section 35 requires that NSIRA submit to the appropriate Minister a report with respect to any activity that is related to national security or intelligence that, in NSIRA’s opinion, may not be in compliance with the law. NSIRA will complete the broader review of DND/CAF’s human source handling activities in 2023.

Canada Border Services Agency

NSIRA completed its first in-depth review of national security or intelligence activities of the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) in 2022: a review of air passenger targeting. This review examined the CBSA’s pre-arrival risk assessment of passengers based on data collected by commercial air carriers. It evaluated whether the CBSA’s activities complied with legislative requirements and Canada’s non-discrimination obligations.

Multi-departmental reviews

NSIRA conducted two mandated multi-departmental reviews in 2022:

- a review of directions issued with respect to the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act; and

- a review of disclosures of information under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act.

Review work not resulting in a final report

During the past year NSIRA determined that certain ongoing review work would be closed or not result in a final report to a Minister. These decisions allow NSIRA to remain nimble and to pivot its work plan. Multiple considerations can lead to the decision to close a review, and doing so allows NSIRA to redirect efforts and resources.

Technology in review

In 2022, NSIRA expanded its Technology Directorate to keep pace with the national security and intelligence community’s evolving use of digital technologies. The team comprises technical experts and review professionals, who are supported by academic researchers. This expanded team launched NSIRA’s first technology-led review, focusing on the lifecycle of warranted CSIS information. In addition to directly supporting NSIRA’s reviews, the Technology Directorate also began hosting learning sessions and discussion forums designed to enhance NSIRA employees’ knowledge of broader technical issues.

Engagement with reviewees

NSIRA continues to address and improve on aspects of its interaction with reviewees during the review process. It saw both improvements and ongoing challenges, and seeks to provide full and transparent assessments in this regard. Updated criteria will be used to evaluate engagement. These criteria are critical for supporting NSIRA’s efforts during a review. This approach builds on the agency’s previous confidence statements and provides a more consistent and complete assessment on engagement.

NSIRA continues to optimize its methods for accessing, receiving and tracking the information required to complete reviews. This involves ongoing discussions and support from reviewees. Limitations and challenges to this process are addressed directly and are communicated publicly where possible.

Complaints investigations

As NSIRA marked its third year of existence in 2022 it continued maturing and modernizing the processes for fulfilling its investigations mandate. The jurisdiction assessment phase was standardized, incorporating a verification protocol for the three agencies for which NSIRA has complaints jurisdiction. To speed up the investigative process, investigative interviews are being used more often, taking over from the formal hearings NSIRA previously relied on.

The pandemic continued to impact the investigative landscape in the first half of 2022. COVID protocols conflicted with security protocols for investigations, which require in-person meetings. Processes introduced in 2022 are expected to reduce delays in the conduct of investigations on a forward basis.

The number of investigation activities last year remained high and included the completion of a referral of a group of 58 complaints by the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

Data management and service standards initiatives that were launched are expected to enhance complaint file management in the coming year.

Partnerships

During the past year, NSIRA expanded its engagement with valuable partners, both domestically and internationally, and has already reaped the benefits through the exchange of best practices. As a relatively new agency, NSIRA sees such relationships as a priority for its institutional development. NSIRA had the privilege of visiting many international partners as an active participant in the Five Eyes Intelligence Oversight and Review Council, and also engaged other European partners through various forums that bring together like-minded oversight, review and data protection agencies from all over the world.

Introduction

1.1 Who we are

Established in July 2019, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) is an independent agency that reports to Parliament. Canadian review bodies before NSIRA did not have the ability to collaborate or share their classified information but were each limited to conducting reviews on a specified department or agency. By contrast, NSIRA has the authority to conduct an integrated review of Government of Canada national security and intelligence activities, and Canada now has one of the world’s most extensive systems for independent review of national security.

1.2 Mandate

NSIRA has a dual mandate to conduct reviews on and carry out investigations of complaints related to Canada’s national security or intelligence activities.

Reviews

NSIRA’s review mandate is broad, as outlined in subsection 8(1) of the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Act (NSIRA Act). This mandate includes reviewing the activities of both the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), as well as the activities of any other federal department or agency that are related to national security or intelligence. Further, NSIRA reviews any national security or intelligence matters that a minister of the Crown refers to NSIRA.

Investigations

In addition to its review mandate, NSIRA is responsible for investigating complaints related to national security or intelligence. This duty is outlined in paragraph 8(1)(d) of the NSIRA Act, and involves investigating complaints about:

- the activities of CSIS or CSE;

- decisions to deny or revoke certain federal government security clearances; and

- ministerial reports under the Citizenship Act that recommend denying certain citizenship applications.

This mandate also includes investigating national security-related complaints referred to NSIRA by the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP (the RCMP’s own complaints mechanism) and the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

Observations and themes

NSIRA has a horizontal, in-depth view of the Canadian national security landscape that allows for an assessment of Canada’s complex, interwoven approach to national security. NSIRA annual reports discuss its activities within that framework. This annual report provides an opportunity to reflect on NSIRA’s body of work horizontally, and consider what broad trends or themes emerge.

NSIRA findings and recommendations touch on many aspects of government activities and operations. Grouping all findings and recommendations according to topics that fall under three broad themes helps simplify a horizontal assessment of trends to date. This categorization and the terminology used may evolve over time.

The themes that emerge are governance; propriety; and information management and sharing. These themes appear year after year in NSIRA annual reports. The following topics are included in these themes:

| Theme | Topics |

|---|---|

| Governance |

|

| Propriety |

|

| Information management and sharing |

|

These themes can be found in every NSIRA annual report, and this year’s is no exception. In this year’s annual report, the following examples illustrate the three themes:

Governance:

- the review of disclosures under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act for 2021 identified that employees did not receive adequate guidance to fulfill their obligations, and recommended improvements to training;

- the review of a CSE foreign intelligence activity identified several instances where the program’s activities were not adequately captured within CSE’s applications for certain ministerial authorizations, resulting in recommendations that CSE more effectively inform the Minister of National Defence about aspects of its bilateral relationships with certain partners, the extent of its participation in certain types of activities, and the testing and evaluation of products.

Propriety:

- in a report issued to the Minister of National Defence under s.35 of the NSIRA Act, NSIRA explained that, in its opinion, certain activities undertaken by the Canadian Armed Forces may not have been in compliance with the law;

- the review of the threat reduction measures of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service found that this agency did not meet its internal policy requirements regarding the timelines to submit threat reduction measure implementation reports.

Information management and sharing:

- the Canada Border Services Agency air passenger targeting review noted that this agency does not document its triaging practices that use passenger data in a manner that enables effective verification of whether all triaging decisions comply with statutory and regulatory restrictions.

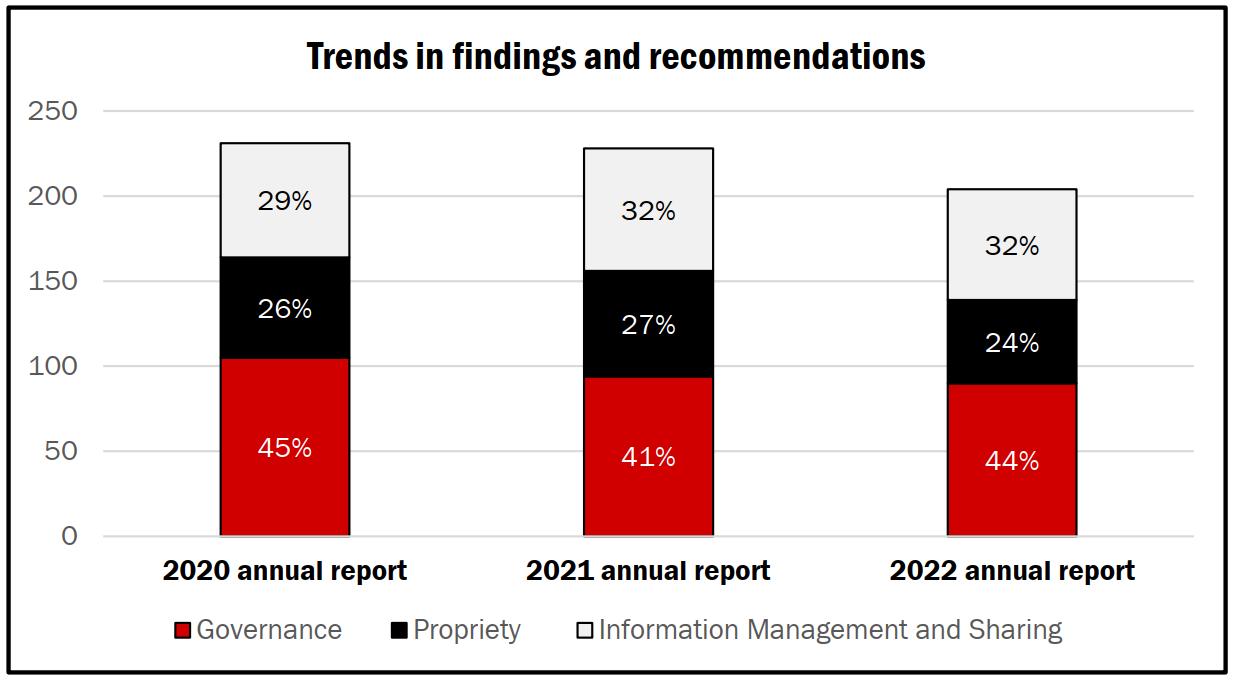

A high-level overview of the past three annual reports shows the number of NSIRA findings and recommendations each year, broken down by theme. Over the three years, governance related findings and recommendations constituted 43% of the overall total. The comparable figures for propriety and information management (IM) and sharing categories were 26% and 31% respectively. The breakdown by year is captured in the following table:

Figure 1: Trends in findings and recommendations

Text version of Figure 1

| 2020 annual report | 2021 annual report | 2022 annual report | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance | 45% | 41% | 44% |

| Propriety | 26% | 27% | 24% |

| Information Management and Sharing | 29% | 32% | 32% |

The interconnected nature of the problems identified in NSIRA reviews, along with the balance of themes illustrated in the graphic above, reveals a narrative. Indeed, issues rarely stand-alone – governance and IM and sharing issues may, for example, culminate in propriety challenges. The number of findings and recommendations over three years that touch on governance, propriety and IM and sharing matters suggest that these are issues deserving close attention. Employees are expected to succeed in meeting intelligence and national security service missions while adhering to policy and legal requirements. Here, improvements to staff training and development are likely to have the most significant impacts.

Review

Details provided on individual reviews are a high-level summary of their content and outcomes. Full versions of each review are available once they have been redacted for public release.

3.1 Canadian Security Intelligence Service reviews

Overview

NSIRA has a mandate to review any Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) activity. The NSIRA Act requires NSIRA to submit an annual report on CSIS activities each year to the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness (with these responsibilities now divided into two portfolios, NSIRA currently submits these reports to the Minister of Public Safety). These classified reports include information related to CSIS’s compliance with the law and applicable ministerial directions, and the reasonableness and necessity of the exercise of CSIS’s powers.

In 2022, NSIRA completed one dedicated review of CSIS, and its annual review of CSIS activities, both summarized below. Furthermore, CSIS is implicated in other NSIRA multi- departmental reviews, such as the legally mandated annual reviews of the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act and the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act, the results of which are described in Multi-departmental reviews.

Threat reduction measures review

This is NSIRA’s third annual review of CSIS threat reduction measures (TRMs), which are measures to reduce threats to the security of Canada, within or outside Canada. Section 12.1 of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act (CSIS Act) authorizes CSIS to take these measures.

NSIRA found that CSIS’s activities under its TRM mandate in 2021 were broadly consistent with these activities in preceding years. NSIRA observed that 2018 was an inflection point for CSIS’s use of the TRM mandate. In that year, CSIS proposed nearly as many TRMs as were proposed in total in the preceding three years — the first three of the mandate. In the following year, however, the number dropped slightly, before a more significant reduction in 2020. The number of proposed TRMs in 2021 went up slightly compared with the previous year, as did both approvals and implementations.

NSIRA selected three TRMs implemented in 2021 for a more intensive review, assessing the measures for compliance with applicable law, ministerial direction and policy. At the same time, NSIRA considered the implementation of each measure, including the alignment between what was proposed and what occurred, and the role of legal risk assessments for guiding CSIS activity, as well as the documentation of outcomes.

For all the measures reviewed, NSIRA found that CSIS met its obligations under the law, specifically the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and sections 12.1 and 12.2 of the CSIS Act. In addition to general legal compliance, NSIRA found that CSIS sufficiently established a “rational link” between the proposed measure and the identified threat.

In one case, NSIRA found that CSIS did not meet its obligations under the 2015 Ministerial Direction for Operations and Accountability and the 2019 Ministerial Direction for Accountability issued by the Minister of Public Safety.

The TRM in question involved certain sensitive factors. NSIRA believes that the presence of these factors ought to have factored into the overall risk assessment of the measure. CSIS argued that risks associated with these factors relate primarily to reputational risk to CSIS, which it assessed in this case. Certain risks related to the sensitive factors, however, are not, and in this instance were not, captured by CSIS’s reputational risk assessment.

Similarly, the legal risk assessment for this TRM did not comply with ministerial direction. NSIRA recommended that legal risk assessments be conducted for TRMs involving these sensitive factors, and further, that CSIS consider and evaluate whether the current process for legal risk assessments complies with applicable ministerial direction.

A comparative analysis of the two legal risk assessments provided for the other TRMs under review underscored the practical utility of clear and specific legal direction for CSIS personnel. Clear direction allows investigators to be aware of, and understand, the legal parameters within which CSIS personnel can operate; it also permits reporting after an action is completed to document how implementation stayed within those legal parameters.

With respect to documenting outcomes, NSIRA further noted issues with how quickly CSIS produces certain reports after a TRM is implemented. Although NSIRA recognizes that overly burdensome documentation requirements can unduly inhibit CSIS activities, NSIRA nonetheless believes that the recommendations provided are prudent and reasonable. Relevant information, available in a timely manner, benefits CSIS operations.

Annual review of Canadian Security Intelligence Service activities

In 2022, NSIRA completed its annual review of CSIS activities, which aims to identify compliance-related challenges, general trends and emerging issues using CSIS documents in 12 categories (legislatively required and supplementary) from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022. Besides contributing to NSIRA’s Annual Report to the Minister of Public Safety on CSIS activities, the review may identify areas that merit new NSIRA reviews and may produce a briefing or report with its own observations, findings and recommendations. NSIRA provided its report on CSIS activities in 2021 to the Minister of Public Safety on October 12, 2022, and the Chair subsequently met with the Minister to discuss its contents as well as ongoing issues and challenges related to NSIRA review of CSIS.

Statistics and data

To achieve greater public accountability, NSIRA has requested that CSIS publish statistics and data about public interest and compliance-related aspects of its activities. NSIRA is of the opinion that the following statistics will provide the public with information related to the scope and breadth of CSIS operations, as well as display the evolution of activities from year to year.

Warrant applications

Section 21 of the CSIS Act authorizes CSIS to make an application to a judge for a warrant if it believes, on reasonable grounds, that more intrusive powers are required to investigate a particular threat to the security of Canada. Warrants may be used by CSIS, for example, to intercept communications, enter a location, or obtain information, records or documents. Each individual warrant application could include multiple individuals or request the use of multiple intrusive powers.

Table 1: Section 21 warrant applications made by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, 2018 to 2022

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total section 21 applications | 24 | 24 | 15 | 31 | 28 |

| Total approved warrants | 24 | 23 | 15 | 31 | 28 |

| New warrants | 10 | 9 | 2 | 13 | 6 |

| Replacements | 11 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 14 |

| Supplemental | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 8 |

| Total denied warrants | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Threat reduction measures

CSIS is authorized to seek a judicial warrant for a TRM if it believes that certain intrusive measures, outlined in section 21 (1.1) of the CSIS Act, are required to reduce the threat. The CSIS Act is clear that when a proposed TRM would limit a right or freedom protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms or would otherwise be contrary to Canadian law, a judicial warrant authorizing the measure is required. To date, CSIS has sought no judicial authorizations to undertake warranted TRMs. TRMs approved in one year may be executed in future years. Operational reasons may also prevent an approved TRM from being executed.

Table 2: Total number of approved and executed threat reduction measures, 2015 to 2022

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Approved threat reduction measures |

10 | 8 | 15 | 23 | 24 | 11 | 23 | 16 |

| Executed | 10 | 8 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 8 | 17 | 12 |

|

Warranted threat reduction measures |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Canadian Security Intelligence Service targets

CSIS is mandated to investigate threats to the security of Canada, including espionage, foreign influenced activities, political, religious or ideologically motivated violence, and subversion.6 Section 12 of the CSIS Act sets out criteria permitting CSIS to investigate an individual, group or entity for matters related to these threats. Subjects of a CSIS investigation, whether they be individuals or groups, are called “targets.”

Table 3: Number of Canadian Security Intelligence Service targets, 2018 to 2022

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of targets | 430 | 467 | 360 | 352 | 340 |

Datasets

Data analytics is a key investigative tool for CSIS, providing it with the capacity to make connections and identify trends that are not possible through traditional methods of investigation. The National Security Act, 2017, which came into force in 2019, gave CSIS new powers, including a legal framework for it to collect, retain and use datasets. The framework authorizes CSIS to collect datasets (divided into Canadian, foreign and publicly available datasets) that have the ability to assist CSIS in the performance of its duties and functions. It also establishes safeguards for the protection of Canadian rights and freedoms, including privacy rights. These protections include enhanced requirements for ministerial accountability. Depending on the type of dataset, CSIS must meet different requirements before it is able to use a dataset.

The CSIS Act also requires that NSIRA be kept apprised of certain dataset-related activities. Reports prepared following the handling of datasets are to be provided to NSIRA, under certain conditions and within reasonable timeframes. While CSIS is not required to advise NSIRA of judicial authorizations or ministerial approvals for the collection of Canadian and foreign datasets, CSIS has been proactively keeping NSIRA apprised of these activities.

Table 4: Evaluation and retention of publicly available, Canadian and foreign datasets by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, 2019 to 2022

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publicly available datasets |

||||

| Evaluated | 9 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Retained | 9 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Canadian datasets | ||||

| Evaluated | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Retained (approved by Federal Court) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Denied by Federal Court | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Foreign datasets | ||||

| Evaluated | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Retained (approved by the Minister and Intelligence Commissioner | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Denied by the Minister | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Denied by the Intelligence Commissioner | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Justification Framework

The National Security Act, 2017, also created a legal justification framework for CSIS’s intelligence collection operations. The framework establishes a limited justification for CSIS employees, and persons acting at their direction, to carry out activities that would otherwise constitute offences under Canadian law. CSIS’s Justification Framework is modelled on those already in place for Canadian law enforcement. The Justification Framework provides needed clarity to CSIS, and to Canadians, as to what CSIS may lawfully do in the course of its activities. It recognizes that it is in the public interest to ensure that CSIS employees can effectively carry out its intelligence collection duties and functions, including by engaging in otherwise unlawful acts or omissions, in the public interest and in accordance with the rule of law. The types of otherwise unlawful acts and omissions that are authorized by the Justification Framework are determined by the Minister and approved by the Intelligence Commissioner. There remain limitations to what activities can be undertaken, and nothing in the Justification Framework permits the commission of an act or omission that would infringe a right or freedom guaranteed by the Charter.

According to section 20.1 (2) of the CSIS Act, employees must be designated by the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness to be covered under the Justification Framework while committing or directing an otherwise unlawful act or omission. Designated employees are CSIS employees who require the justification framework as part of their duties and functions. Designated employees are justified in committing an act or omission themselves (commissions by employees) and they may direct another person to commit an act or omission (directions to commit) as a part of their duties and functions.

Table 5: Authorizations, commissions and directions under the Justification Framework, 2019 to 2022

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authorizations | 83 | 147 | 178 | 172 |

|

Commissions by employees |

17 | 39 | 51 | 61 |

| Directions to commit | 32 | 84 | 116 | 131 |

| Emergency designations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Compliance

CSIS’s internal operational compliance program unit leads and manages overall compliance within CSIS. The objective of this unit is to promote a culture of compliance within CSIS by leading an approach for reporting and assessing potential non-compliance incidents to provide timely advice and guidance related to internal policies and procedures for employees. This program is the centre for processing all instances of potential non-compliance related to operational activities.

NSIRA notes that CSIS reports Charter violations as operational non-compliance. NSIRA will continue to monitor closely instances of non-compliance that relate to Canadian law and the Charter, and work with CSIS to improve transparency around these activities.

Table 6: Total number of non-compliance incidents processed by CSIS, 2019 to 2022

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Processed compliance incidents |

53 | 99 | 85 | 59 |

|

Administrative |

53 | 64 | 42 | |

| Operational | 40 | 19 | 21 | 17 |

| Canadian law |

– | – | 1 | 2 |

| Charter | – | – | 6 | 5 |

| Warrant conditions | – | – | 6 | 3 |

| CSIS governance | – | – | 8 | 15 |

3.2 Communications Security Establishment reviews

Overview

NSIRA has the mandate to review any activity conducted by the Communications Security Establishment (CSE). NSIRA must also submit an annual report to the Minister of National Defence on CSE activities, including information related to CSE’s compliance with the law and applicable ministerial directions, and NSIRA’s assessment of the reasonableness and necessity of the exercise of CSE’s powers.

In 2022, NSIRA completed two dedicated reviews of CSE and commenced an annual review of CSE activities, all summarized below. Furthermore, CSE is implicated in other NSIRA multi- departmental reviews, such as the legally mandated annual reviews of the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act and the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act, the results of which are described in Multi-departmental reviews.

Review of the Communications Security Establishment’s active and defensive cyber operations

The Communications Security Establishment Act (CSE Act) grants CSE the authority to conduct active cyber operations and defensive cyber operations (ACOs and DCOs). CSE ACOs and DCOs have become a tool of Government of Canada foreign and security policy. In 2021, NSIRA reviewed CSE’s governance of and the general planning and approval process for ACO and DCO activities. The governance review made several observations about the governance of ACOs and DCOs by CSE — and to a lesser extent, by Global Affairs Canada (GAC). Some of these observations identified gaps that resulted in recommendations. Building on the governance review, the report focused on CSE’s ACOs and DCOs themselves:

- the operations;

- the implementation of CSE’s governance; and

- the legal framework in the context of specific ACOs and DCOs.

NSIRA incorporated GAC, CSIS, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and DND/CAF into this review, given these organizations’ varying degrees of coordination or involvement in these CSE activities. NSIRA also inspected some technical elements of a case study ACO to verify aspects of the operation independently, as well as to deepen NSIRA’s understanding of how an ACO works. While NSIRA reviewed all ACOs and DCOs planned or conducted by CSE until mid-2021, this review focused on a sample of such ACOs or DCOs, each presenting unique characteristics.

Overall, NSIRA found that ACOs and DCOs that CSE planned or conducted during the period of review were lawful and noted improvements in GAC’s assessments for foreign policy risk and international law. NSIRA further observed that CSE developed and improved its processes for the planning and conduct of ACOs and DCOs in a way that reflected some of NSIRA’s observations from the governance review.

NSIRA also made findings pertaining to how CSE could improve aspects of ACO and DCO planning, as well as communication to the Minister of National Defence and coordination with other Government of Canada entities. More specifically, NSIRA identified areas of potential risk:

- GAC’s capability to independently assess potential risks resulting from CSE ACOs and DCOs;

- the accuracy of information provided, and issues related to delegation, within some of the applications for authorizations for ACOs and DCOs;

- the degree to which CSE engaged with CSIS and the RCMP on ACOs and DCOs, and CSE explanations of how it determined whether the objective of an ACO or DCO could not reasonably be achieved by other means;

- the extent to which CSE described the intelligence collection that may occur alongside or as a result of ACOs or DCOs in applications for ACO and DCO authorizations and in operational documentation; and

- overlap between activities conducted under the ACO and DCO aspects of CSE’s mandate as well as under all four aspects of CSE’s mandate.

It should be noted that NSIRA faced significant challenges in accessing CSE information on this review. These access challenges had a negative impact on the review. As a result, NSIRA could not be confident in the completeness of information provided by CSE.

Review of a foreign intelligence activity

In 2022, NSIRA completed a review of a sensitive CSE foreign intelligence collection program. As part of this review, NSIRA made several findings and observations regarding the activities carried out as part of this program. Notably, NSIRA identified several instances where the program’s activities were not adequately captured within CSE’s applications for certain ministerial authorizations. As such, NSIRA recommended that CSE more effectively inform the Minister of National Defence about aspects of its bilateral relationships with certain partners, the extent of its participation in certain types of activities, and the testing and evaluation of products.

NSIRA also found several areas where the program lacked adequate governance structures, resulting in improper application of key policy and procedural requirements related to information sharing, confirmation of foreignness, and CSE’s mistreatment risk assessment process. NSIRA made recommendations to strengthen these processes, to establish governance structures specific to the program, and to improve other governance structures with broader applicability throughout CSE.

Annual review of Communications Security Establishment activities

In 2022, NSIRA launched the annual review of CSE activities, which aimed to identify compliance-related challenges, general trends and emerging issues using CSE documents in 11 categories (legislatively required and supplementary) from January 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022. Besides contributing to NSIRA’s Annual Report to the Minister of National Defence on CSE activities, the review may identify areas that merit new NSIRA reviews and may produce a briefing or report with its own observations, findings and recommendations. It is based largely on the structure of the annual review of CSIS activities but has been adapted to CSE. NSIRA’s Chair met with the Minister of National Defence on December 15, 2022 to discuss ongoing issues and challenges related to NSIRA reviews of CSE activities.

Statistics and data

To achieve greater accountability and transparency, NSIRA has requested statistics and data from CSE about public interest and compliance-related aspects of its activities. NSIRA is of the opinion these statistics will provide the public with important information related to the scope and breadth of CSE operations, as well as display the evolution of activities from year to year.

Ministerial authorizations and ministerial orders

Ministerial authorizations are issued to CSE by the Minister of National Defence. Those authorizations support specific foreign intelligence or cybersecurity activities or defensive or active cyber operations conducted by CSE pursuant to those aspects of the CSE mandate. Authorizations are issued when these activities could otherwise contravene an Act of Parliament or interfere with a reasonable expectation of privacy of a Canadian or a person in Canada.

Table 7: Ministerial authorizations issued, 2019 to 2022

| Type of ministerial authorization | Enabling section of the CSE Act | Issued in 2019 | Issued in 2020 | Issued in 2021 | Issued in 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Foreign intelligence |

26(1) |

3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

|

Cybersecurity — federal and non-federal |

27(1) and 27(2) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Defensive cyber operations | 29(1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Active cyber operations | 30(1) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Note: This table lists ministerial authorizations that were issued in a given calendar year and may not necessarily reflect ministerial authorizations that were in effect at a given time. For example, if a ministerial authorization was issued in late 2021 and remained in effect in parts of 2022, it is counted solely as a 2021 ministerial authorization.

Ministerial orders are issued by the Minister for the purpose of (1) designating any electronic information, any information infrastructures or any class of electronic information or information infrastructures as electronic information or information infrastructures of importance to the Government of Canada (section 21(1) of the CSE Act); or (2) designating recipients of information related to Canadians or persons in Canada, that is, Canadian- identifying information (sections 45 and 44(1) of the CSE Act).

Table 8: Ministerial orders in effect as of 2022

| Name of ministerial order | Enabling section of the CSE Act |

|---|---|

|

Designating electronic information and information infrastructures of importance to the Government of Canada |

21(1) |

|

Designating recipients of information relating to a Canadian or person in Canada acquired, used or analyzed under the cybersecurity and information assurance aspects of the CSE mandate |

45 and 44(1) |

| Designating recipients of Canadian identifying information used, analyzed or retained under a foreign intelligence authorization pursuant to section 45 of the CSE Act |

45 and 43 |

|

Designating electronic information and infrastructures of Ukraine as Systems of Importance |

21(1) |

| Designating electronic information and infrastructures of Latvia as Systems of Importance | 21(1) |

Note: Ministerial orders remain in effect until rescinded by the Minister.

Foreign intelligence reporting

Under section 16 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to acquire information from or through the global information infrastructure. The CSE Act defines the global information infrastructure as including electromagnetic emissions, any equipment producing such emissions, communications systems, information technology systems and networks, and any data or technical information carried on, contained in or relating to those emissions, that equipment, those systems or those networks. CSE uses, analyzes and disseminates the information for providing foreign intelligence in accordance with the Government of Canada’s intelligence priorities.

Table 9: Number of foreign intelligence reports issued, 2019 to 2022

| CSE foreign intelligence reporting | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of reports released |

N/A | N/A | 3,050 | 3,185 |

|

Number of departments/agencies |

N/A | >25 | 28 | 26 |

| Number of specific clients within departments/agencies | N/A | >2,100 | 1,627 | 1,761 |

Note: NSIRA did not ask CSE for statistics related to foreign intelligence reporting for its 2019 public annual report. In 2020, statistics were requested, but were provided in general terms due to the classification of the data at the time, and CSE indicated that release of further detail, would be injurious to national security.

Information relating to a Canadian or a person in Canada

Information relating to a Canadian or a person in Canada (IRTC) is the information about Canadians or persons in Canada that may be incidentally collected by CSE while conducting foreign intelligence or cybersecurity activities under the authority of a ministerial authorization. Incidental collection refers to information acquired that CSE was not deliberately seeking, and where the activity that enabled the acquisition of this information was not directed at a Canadian or a person in Canada. According to CSE policy, IRTC is defined as any information recognized as having reference to a Canadian or person in Canada, regardless of whether that information could be used to identify that Canadian or person in Canada.

CSE was asked to release statistics or data about the regularity with which IRTC or “Canadian- collected information” is included in CSE’s end-product reporting. CSE responded that “this information remains at a classified level. We have determined that the release of thisinformation would be injurious to Canada’s international relations, national defence and security. Furthermore, the sharing of this information would provide an additional level of detail on the success of Canadian collection programs, our level of reliance on information from Five- Eye partners to produce intelligence, as well as a level of detail on Five-Eye use and reporting from Canadian collection that has not been previously made public.”

Canadian identifying information

CSE is prohibited from directing its activities at Canadians or persons in Canada. However, CSE’s collection methodologies sometimes result in incidentally acquiring such information. When such incidentally collected information is used in CSE’s foreign intelligence reporting, any part potentially identifying a Canadian or a person in Canada is suppressed to protect the privacy of the individual(s) in question. CSE may release unsuppressed Canadian-identifying information (CII) to designated recipients when the recipients have the legal authority and operational justification to receive it and when it is essential to international affairs, defence or security (including cyber security).

Table 10: Number of requests for disclosure of CII, 2021 and 2022

| Type of request | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

|

Government of Canada requests |

741 | 657 |

|

Five Eyes requests |

90 | 62 |

| Non-Five Eyes requests |

0 | 0 |

| Total | 831 | 719 |

In 2022, of the 719 requests received, CSE reported having denied 65 requests. By the end of the year, 51 were still being processed.

CSE was asked to release the number of instances where CII is suppressed in CSE foreign intelligence or cyber security reporting. It indicated that “[d]isclosure of the number of instances where [CII] is suppressed in CSE intelligence reporting would be injurious to CSE’scapabilities. Such a disclosure would reveal information about CSE’s capabilities including theirlimitations. Thus, this information could be used by hostile security threats to counter CSE’s capabilities impeding CSE’s ability to protect Canada and its citizens.”

Privacy incidents and procedural errors

A privacy incident occurs when the privacy of a Canadian or a person in Canada is put at risk in a manner that runs counter to, or is not provided for, in CSE’s policies. CSE tracks such incidents via its Privacy Incidents File and, for privacy incidents that are attributable to a second-party partner or a domestic partner, its Second-party Privacy Incidents File.

Table 11: Number of privacy incidents recorded by CSE, 2021 and 2022

| Type of incident | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy incidents | 96 | 114 |

| Second-party privacy incidents | 33 | 23 |

Cyber security and information assurance

Under section 17 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to provide advice, guidance and services to help protect electronic information and information infrastructures of federal institutions, as well as those of non-federal entities that are designated by the Minister as being of importance to the Government of Canada.

The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) is Canada’s unified authority on cybersecurity. The Cyber Centre, which is a part of CSE, provides expert guidance, services and education, while working in collaboration with stakeholders in the private and public sectors. The Cyber Centre handles incidents in government and designated institutions that include:

- reconnaissance activity by sophisticated threat actors;

- phishing incidents, that is, email containing malware;

- unauthorized access to corporate information technology (IT) environments;

- imminent ransomware attacks; and

- zero-day exploits, which involves exploration of critical vulnerabilities in unpatched software.

Table 12: Number of cyber incident cases opened by CSE, 2022

| Type of incident | 2022 |

|---|---|

| Federal institutions | 1,070 |

| Critical infrastructure | 1,575 |

| Total | 2,645 |

Defensive and active cyber operations

Under section 18 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to conduct DCOs to help protect electronic information and information infrastructures of federal institutions, as well as those of non- federal entities that are designated by the Minister as being of importance to the Government of Canada from hostile cyber attacks.

Under section 19 of the CSE Act, CSE is mandated to conduct ACOs against foreign individuals, states, organizations or terrorist groups as they relate to international affairs, defence or security.

CSE was asked to release the number of DCOs and ACOs approved, and the number carried out, during 2022. CSE responded that it is “not in a position to provide this information for publication by NSIRA, as doing so would be injurious to Canada’s international relations,national defence, and national security.”

Technical and operational assistance

As part of the assistance aspect of CSE’s mandate, CSE receives requests for assistance from Canadian law enforcement and security agencies, as well as from the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (DND/CAF).

Table 13: Number of requests for assistance received and actioned by CSE, 2020 to 2022

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approved | 23 | 32 | 59 |

| Not approved | 1 | 3 | Not applicable |

| Cancelled | Not available | Not available | 1 |

| Denied | Not available | Not available | 2 |

| Total received | 24 | 35 | 62 |

3.3 Other departments

Overview

In addition to the CSIS and CSE reviews above, NSIRA completed the following reviews of departments and agencies in 2022:

- A review of the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces;

- A review of the Canada Border Services Agency; and

- NSIRA’s annual reviews of both the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act and the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act, both of which involve a broader set of departments and agencies that make up the Canadian national security and intelligence community.

Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces

Report issued pursuant to section 35 of the NSIRA Act

In the course of a review of the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (DND/CAF) human source handling activities, which was still ongoing at the time of writing, NSIRA issued on December 9, 2022, a report under section 35 of the NSIRA Act to the Minister of National Defence. According to section 35, NSIRA must submit to the appropriate minister a report with respect to any activity that is related to national security or intelligence that, in NSIRA’s opinion, may not be in compliance with the law. The Minister of National Defence submitted a copy of this report to the Attorney General of Canada and included her comments indicating that her interpretation of the facts and law differs from NSIRA’s. NSIRA stands by its position and is of the view that the Minister’s position is based on a narrow interpretation of the facts and the law. NSIRA will complete the larger review of DND/CAF’s human source handling activities in 2023. While the section 35 report does not include recommendations, the broader review will examine accountability and oversight of the program, its risk framework, and DND/CAF’s discharge of its duty of care with respect to human sources. The review also assesses the lawfulness of the program and its related activities, as well as the sufficiency of its legal and policy foundations. In doing so, the report may include recommendations addressing the observations made in the section 35 report.

Canada Border Services Agency

Air passenger targeting review

The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) air passenger targeting program uses pre-arrival risk assessments to identify inbound air travellers at higher risk of being inadmissible to Canada or whose entry, or that of their goods, may otherwise contravene the CBSA’s program legislation.

The first step in these multi-stage assessments is to triage travellers based on the characteristics and travel patterns conveyed to the CBSA by commercial air carriers in AdvancePassenger Information and Passenger Name Record data. This triage may be manual (flight list targeting) or automated (scenario-based targeting). In both methods, the CBSA relies on information and intelligence from a variety of sources to determine which data elements to treat as indicators of risk in relation to particular enforcement issues, including those related to national security. Use of these indicators may lead the CBSA to differentiate among travellers in subsequent stages of targeting or at the border, with impacts on passengers’ time, privacy and equal treatment.

The review of air passenger targeting was NSIRA’s first in-depth assessment of the CBSA’s compliance with relevant law. It focused, first, on whether the CBSA complies with restrictions on the use of passenger data established by the Customs Act and the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations. Next, the review examined whether the CBSA’s use of these types of passenger data was discriminatory under the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

NSIRA found that the CBSA’s use of both types of passenger data in scenario-based targeting was for a purpose authorized by the Customs Act. For flight list targeting, however, the CBSA does not document the reasons underpinning its triage decisions. NSIRA was therefore unable to verify compliance of flight list targeting with the purpose limitations set out in the Customs Act. As well, the documentation did not allow NSIRA to verify that the CBSA’s use of Passenger Name Record data in either triage method complied with the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations, which require that access to retained data be for a purpose related to the identification of persons who have or may have committed a terrorism offence or serious transnational crime.

NSIRA also found that the CBSA did not consistently demonstrate an adequate justification for its selection of particular indicators as signals of increased risk. When adequate justification is not present, differentiating among passengers on the basis of prohibited grounds of discrimination (such as age, national or ethnic origin, or sex) creates a risk of discrimination.

NSIRA recommended that the CBSA document its triage practices in a manner that demonstrates compliance with the Customs Act and, where applicable, the Protection of Passenger Information Regulations. It recommended that the CBSA ensure, in an ongoing manner, that its selection of risk indicators be adequately justified based on well-documented information or intelligence. NSIRA further recommended that the CBSA develop more robust and regular oversight of air passenger targeting, including updates to policies, procedures, training and other guidance. NSIRA also recommended that the CBSA begin collecting the data necessary to identify, analyze and mitigate discrimination-related risks stemming from air passenger targeting.

3.4 Multi-departmental reviews

Review of federal institutions’ disclosures of information under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act in 2021

The review of federal institutions’ disclosures of information under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act (SCIDA) in 2021 describes the results of a review of the 2021 disclosures made by federal institutions under this legislation. In 2022, NSIRA focused the review on Global Affairs Canada (GAC)’s proactive disclosures.

The SCIDA encourages and facilitates the disclosure of information between federal institutions to protect Canada against activities that undermine or threaten national security, subject to certain conditions. The SCIDA provides a two-part threshold that must be met before an institution can make a disclosure:

- that the information will contribute to the exercise of the recipient institution’s jurisdiction or responsibilities in respect of activities that undermine the security of Canada (paragraph 5(1)(a)); and

- that the information will not affect any person’s privacy interest more than reasonably necessary in the circumstances (paragraph 5(1)(b)).

The SCIDA also includes provisions and guiding principles related to the management of disclosures, including accuracy and reliability statements and record keeping obligations.

NSIRA identified concerns that demonstrate the need for GAC to improve its training. NSIRA found that there is potential for confusion on whether the SCIDA is the appropriate mechanism for certain disclosures of national security–related information. For some disclosures, GAC did not meet the two-part threshold requirements of the SCIDA before disclosing the information, which was not compliant with the SCIDA. Two disclosures did not contain accuracy and reliability statements, as required under the SCIDA. With respect to record keeping, NSIRA recommended that departments document, at the same time as they are deciding to disclose information under the SCIDA, the information they are relying on to satisfy themselves that the disclosure is authorized under the Act (paragraph 9(1)(e)).

Review of departmental implementation of the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act for 2021

This review focused on departmental implementation of directions received through orders in council issued under the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACA). This was NSIRA’s third annual statutorily mandated review of the implementation of all directions issued under the ACA. It assessed departments’ implementation of the directives received under the ACA and their operationalization of frameworks to address ACA requirements. As such, this review constitutes the first in-depth examination of the ACA within individual departments.

This year’s review covered the 2021 calendar year and was split into three sections. Section one addressed the statutory obligations of all departments. Sections two and three were an in- depth analysis of how the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Global Affairs Canada (GAC) have implemented the directions under the ACA. NSIRA used case studies, where possible, to examine these departments’ implementation of their ACA framework.

This was the third consecutive year where no cases were referred to the deputy head level in any department. This is a requirement of the orders in council when officials are unable to determine if the substantial risk can be mitigated. Future reviews will be attuned to the issue of case escalation and departmental processes for decision-making.

In the 2019 NSIRA Review of Departmental Frameworks for Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities14, NSIRA recommended that “the definition of substantial risk should be codified in law or public direction.” NSIRA noted that some departments have accounted for this gap by relying on the definition of substantial risk in the 2017 ministerial directions. In light of the pending statutorily mandated review of the National Security Act, 2017 and the importance of the concept of substantial risk to the ACA regime, NSIRA reiterated its 2019 recommendation that the definition of substantial risk be codified in law.

In the review of departmental implementation of ACA in 2020, NSIRA identified the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) and Public Safety Canada as not yet having finalized their ACA policies. While the CBSA and Public Safety Canada continue to make advancements, these departments have not fully implemented an ACA framework and supporting policies and procedures.

The RCMP has a robust framework in place for the triage and processing of cases pertaining to the ACA. The in-depth analysis portion of this review found that the RCMP does not have a centralized system of documenting assurances and does not regularly monitor and update the assessment of the reliability of assurances. The RCMP has also not developed mechanisms to update country and entity profiles in a timely manner, and the information collected throughthe liaison officer during an operation is not centrally documented such that it can inform future assessments.

In the analysis of one of the RCMP’s Foreign Information Risk Advisory Committee case files, NSIRA found that the RCMP’s Assistant Commissioner’s rationale for rejecting the risk advisory committee’s advice did not adequately address concerns consistent with the provisions of the orders in council. In particular, NSIRA found that the Assistant Commissioner erroneously considered the importance of the potential future strategic relationship with a foreign entity in the assessment of potential risk of mistreatment of the individual.

NSIRA found that GAC is now strongly dependent on operational staff and heads of mission for decision-making and accountability under the ACA. This is a marked change from the findings of the 2019 review that found decision-making was done by the Ministerial Direction Compliance Committee at Headquarters.

GAC has also not conducted an internal mapping exercise to determine which business lines are most likely to be implicated by the ACA. Considering the low number of cases this year and the size of GAC, and that ACA training is not mandatory for staff, NSIRA has concerns that not all areas involved in information sharing within Global Affairs Canada are being properly informed of their ACA obligations.

NSIRA also notes that GAC has no formalized tracking or documentation mechanism for the follow-up of caveats and assurances. This is problematic as mission staff are rotational and may therefore have no knowledge of previous caveats and assurances related to prior information sharing instances.

3.5 Closed review work

This past year NSIRA determined that certain ongoing review work would be closed or not result in a final report to a Minister. These decisions allow NSIRA to remain nimble and to pivot its work plan. Considerations such as shifting priorities, resourcing demands, ongoing work taking place within the reviewed department, and deconfliction with partner review agencies can all be factors that lead to a decision to close a review. Such decisions allow NSIRA to redirect its efforts and resources towards other important issues, and thereby maximize the value of its work.

For example, a review of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s (RCMP) Operations Research Branch was closed. A contributing factor in this decision was that the RCMP branch in question ceased to operate. Another example is the decision to cease an ongoing review of how the RCMP handles encryption in the interception of private communications in national security criminal investigations. This review was cancelled to support deconfliction efforts with the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians (NSICOP), who were conducting a similar review. Finally, a review of the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre’s (FINTRAC) terrorist financing and information sharing regime, which was in its early stages, was cancelled at the same time that NSIRA decided to initiate a review of the Canada Revenue Agency’s (CRA) Review and Analysis Division, which delivers the CRA’s anti- terrorism mandate.

3.6 Technology in review

Integration of technology in review

Digital technologies continue to play a crucial role in the operational activities of Canada’s national security and intelligence community as agencies increasingly use new technologies to meet their mandates, propose new avenues for activities, and monitor new threats.

It remains essential for an accountability body like NSIRA to keep pace with the use of digital technologies in Canada’s national security and intelligence community. By staying apprised of rapidly changing technology ecosystems, NSIRA can ensure that the organizations it reviews are pursuing their mandates lawfully, reasonably and appropriately.

NSIRA’s Technology Directorate is a team of engineers, computer scientists, technologists andtechnology review professionals. The mandate of NSIRA’s Technology Directorate is to:

- lead the review of Information Technology (IT) systems and capabilities;

- assess a reviewed entity’s IT compliance with applicable laws, ministerial direction andpolicy;

- conduct independent technical investigations;

- recommend IT system and data safeguards to minimize the risk of legal non-compliance;

- produce reports explaining and interpreting technical subjects;

- lead the integration of technology themes into yearly NSIRA review plans;

- leverage external expertise in the understanding and assessment of IT risks; and

- support assigned NSIRA members in the investigation of complaints against CSIS, CSE or the RCMP when technical expertise is required to assess the evidence.

In 2022, the Technology Directorate grew from one full-time employee to three and welcomed a cooperative education student and two external researchers. With its increased capacity, the Technology Directorate expanded its analysis of technologies in many NSIRA reviews, started formalizing its research methodology, and began hosting micro-learning sessions and discussion forums focused on relevant technical issues, including dark patterns, open-source intelligence and encryption.

The Technology Directorate also began establishing an academic research network with the goal of supporting NSIRA reviews. To date, contributors to the research network have produced valuable internal memos, reports, and discussion forums, which have enhanced NSIRA’s knowledge of a broad set of technical issues.

During the last year, the Technology Directorate also launched NSIRA’s first technology-led review, which focuses on the lifecycle of CSIS information collected by technical capabilities under a Federal Court warrant. This review presents an opportunity for NSIRA to draw on technical standards and review processes used by its Five Eyes peers and the international review and oversight community. NSIRA has been using this review to develop a risk assessment model and technical inspection plan, expanding NSIRA’s broader review toolkit.

Future of technology in review

During the next year, NSIRA will continue to hire more full-time employees in the Technology Directorate, support cooperative education and use external researchers to add capacity. Doing so will augment NSIRA’s ability to keep pace with the rapidly changing and expanding use of digital technologies in Canada’s national security and intelligence ecosystem.

Building on the successes of its budding academic research network, the Technology Directorate intends to prioritize unclassified research on a number of topics, including open- source intelligence, advertising technologies and metadata (content versus non-content data).

NSIRA’s Technology Directorate will also support NSIRA’s complaint investigations team to understand where and when technology factors into their processes and pursuits.

3.7 Engagement with reviewees

Improvements and ongoing challenges

As discussed in previous annual reports, as a new review body, NSIRA experienced initial challenges in its interactions with departments and agencies being reviewed. These challenges are continually being addressed and NSIRA’s relationship with reviewees has matured. While work on this front is not done, reviewees have demonstrated improvements in cooperation and support to the independent review process. The following discussion captures general commentary on the overall engagement with reviewees that were the focus of the past year’s reviews. These overviews cover 2022 and up to the date of writing of this report. Related review-specific commentary or issues, where available, are discussed within each review’s overview above.

Canadian Security Intelligence Service

After temporary restrictions and adjustments related to COVID-19 were lifted, NSIRA returned to its pre-pandemic level of occupancy within CSIS headquarters for CSIS-related reviews. This includes dedicated workspace and building passes for NSIRA employees reviewing CSIS activities. NSIRA employees have direct access to CSIS databases, and CSIS provides any training necessary, when requested, to navigate and access those systems. Generally, CSIS responds to NSIRA requests for information in a reasonably timely manner. Delays and challenges occur on occasion, but communication between NSIRA and CSIS is constructive in resolving issues.

Communications Security Establishment

NSIRA continued to use the space it procured within CSE’s headquarters in the Edward Drake Building to conduct review-related business. There was little improvement in 2022 to NSIRA’s access requirements at CSE. However, as of 2023, NSIRA is piloting limited direct access to CSE’s primary corporate document repository, GCDOCS. Issues remain and NSIRA is not in a position to assess the pilot project’s utility. In some instances, CSE has improved its responsiveness to NSIRA information requests in terms of timeliness, although some challenges remain with the quality of responses. NSIRA continues to work diligently with CSE to address these concerns.

Department of National Defence

Discussions continue with respect to developing dedicated office space and access to networks. While there has been little advancement on longer-term solutions, DND/CAF has worked with NSIRA to provide access to relevant documents, including sensitive files. DND/CAF has provided good access to facilities and people. Generally, responses to requests for information have been timely; however, a lack of proactiveness in DND/CAF disclosures has required NSIRA to send additional requests to ensure completeness and accuracy of information. Overall, the communication between NSIRA and DND/CAF has been constructive.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The past year was marked by inconsistencies in the RCMP’s responsiveness to NSIRA’s requests for information. The RCMP has taken steps to add to its capacity to respond to NSIRA, and this has yielded positive results. NSIRA does not have direct access to information systems but has been granted access to the files relevant to the matters under review. NSIRA has, on multiple occasions, had to send additional requests to ensure the completeness of files provided. In most cases, materials are reviewed on site in the dedicated NSIRA office space that has been provided within RCMP Headquarters. Despite challenges earlier in the year, NSIRA generally had access to people, including RCMP regular members who are experts in the areas under review. Overall, the engagement between NSIRA and the RCMP has seen improvements.

Global Affairs Canada

GAC has been responsive to NSIRA’s requests, made effort to clarify requests, and facilitated all meetings requested. During the review of departmental implementation of the Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act for 2021, GAC provided NSIRA with documents requested within a reasonable time frame. NSIRA did not have direct access to GAC systems, however this did not have an impact on NSIRA’s ability to verify information or access sensitive files as GAC was able to transfer all materials requested either by email or through their secure portal.

Canada Border Services Agency

The CBSA has provided NSIRA with adequate access to information and people. Some challenges in terms of timeliness were resolved promptly after NSIRA sent notice of a pending advisory letter. These challenges appear to be related to the CBSA’s lengthy approval process for the release of documents to NSIRA. NSIRA does not have direct access to CBSA systems, but this has not impeded NSIRA’s access to sensitive files. Overall, the CBSA has been responsive to NSIRA requests, ensuring that CBSA employees are available to answer NSIRA’s questions.

Refining NSIRA’s confidence statements

Assessing responsiveness and verification

NSIRA continues to place importance on assessing the overall quality and efficiency of its interactions with reviewees. Previously, NSIRA captured this assessment in a “confidence statement,” which provided important additional context to the review, apprising readers of the extent to which NSIRA was able to verify necessary or relevant information, and therefore whether its confidence in the information was impacted. These statements were also informed by aspects such as access to information systems and delays in receiving requested information.

NSIRA has further refined and standardized its approach for evaluating the key aspects of its interactions with reviewees and going forward will evaluate the following criteria during each review:

- timeliness of responses to requests for information;

- quality of responses to requests for information;

- access to systems;

- access to people;

- access to facilities;

- professionalism; and

- proactiveness.

Follow-up on timeliness and advisory letters

NSIRA’s 2021 public annual report committed to addressing the ongoing struggle for timely responses from reviewees for requested information. During the past year, all delays have been captured by a request for information tracking system. The results inform one of the criteria discussed above. Additionally, NSIRA continues to leverage its three-staged approach to address continued delays by sending advisory letters to senior officials and ultimately respective Ministers should delays persist. This advisory tool was used at five occasions in 2022, three of which were sent to CSE, and two to the RCMP.

Advisory letters sent to a reviewee during a review may be appended to the final report for both the appropriate minister’s and the public’s awareness of such delays. Combined with the updated assessment criteria discussed above, NSIRA works to provide transparency and awareness of both the challenges and successes on interactions with those reviewed.

Complaints investigations

4.1 Overview

In the three years since its establishment, NSIRA has focused on reforming the investigative process for complaints and developing procedures and practices to ensure the conduct of investigations is fair, timely and transparent. NSIRA previously reported on the creation of its Rules of Procedure, on its policy to commit to the publishing of redacted investigation reports, and on the implementation of the use of video technology. In the past year, NSIRA streamlined its jurisdictional assessment phase and its investigative process through the increased use of investigative interviews as the principal means of fact finding. These developments enabled NSIRA to deal with a significant volume of complaints over this reporting period.